Title Thumbanil & Hero Image: Sri Kṛṣṇa, source: www.pinterest.com, access date: November 1, 2025

B01. Introduction (Extended 2) - Mahābhārata

First revision: Nov.1, 2025

Last change: Nov.11, 2025

Searched, gathered, rearranged, translated, and compiled by Apirak Kanchannakongkha.

1.

xvii

Introduction

The Hindu tradition has an amazingly large corpus of religious texts, spanning Vedas, Vedanta (brāhmaṇas,1 āraṇyakas,2 Upaniṣads,), Vedāṅgas,3,01. smṛtis, Purāṇas, dharmaśāstras, and itihāsa. For most of these texts, especially if one excludes classical Sanskrit literature, we do not quite know when they were composed and by whom, not that one is looking for single authors. Some of the minor Purāṇas (Upapurāṇa) are of a later vintage. For instance, the Bhaviṣya Purāṇa (which is often listed as a major Purāṇa or Mahā Purāṇa) mentions Queen Victoria.

In the listing of the corpus above figures itihāsa, translated into English as history. History does not entirely capture the nuance of itihāsa, which is better translated as ‘this is indeed what happened’. Itihāsa is not myth or fiction. It is a chronicle of what happened; it is a fact. Or so runs the belief. And itihāsa consists of India’s two major epics, the Rāmāyaṇa and the Mahābhārata. The former is believed to have been composed as poetry and the latter as prose. This is not quite correct. The Rāmāyaṇa has segments in prose, and the Mahābhārata has segments in poetry. Itihāsa does not quite belong to the category of religious texts in a way that the Vedas and Vedānta are religious. However, the dividing line between what is religious and what is not is fuzzy. After all, itihāsa is also about attaining the objectives of dharma,4

---------------

1. brāhmaṇa is a text and also the word used for the highest caste.

2. A class of religious and philosophical texts that are composed in the forest, or are meant to be studied when one retires to the forest.

3. The six Vedangas are śikṣā (articulation and pronunciation), chhanda (prosody), vyākaraṇa (grammar ), nirukta (etymology), jyotiṣa (astronomy), and kalpa (rituals).

4. Religion, duty.

Notes & Narratives

01. The Vedāṅga (vedāṅga, "limbs of the Veda") are six auxiliary disciplines traditionally associated with the study and understanding of the Vedas.

1) Shiksha (śikṣā): phonetics, phonology and morphophonology (sandhi)

2) Kalpa (kalpa): ritual

3) Vyakarana (vyākaraṇa): grammar

4) Nirukta (nirukta): etymology

5) Chandas (chandas): meter

6) Jyotisha (jyotiṣa): astronomy

Traditionally, vyakarana and nirukta are common to all four vedas, whilst each veda has its own shiksha, chandas, kalpa and jyotisha texts.

1.

2.

xviii

artha,1 kama2, and mokṣa3 and the Mahābhārata includes Hinduism’s most important spiritual text – the Bhagavad Gītā.

The epics are not part of the śruti tradition. That tradition is like a revelation, without any composer. The epics are part of the smṛti tradition. At the time they were composed, there was no question of texts being written down. They were recited, heard, memorized, and passed down through the generations. But the smṛti tradition had composers. The Rāmāyaṇa was composed by Vālmīki, regarded as the first poet or kavi. The word kavi has a secondary meaning as poet or rhymer. The primary meaning of kavi is someone who is wise.

Vedavyāsa, developed on November 9, 2025.

Vedavyāsa, developed on November 9, 2025.1.

And in that sense, the composer of the Mahābhārata was no less wise. This was Vedavyāsa or Vyāsadeva. He was so named because he classified (vyāsa) the Vedas. Vedavyāsa or Vyāsadeva is not a proper name. It is a title. Once in a while, in accordance with the needs of the era, the Vedas need to be classified. Each such person obtains the title, and there have been twenty-eight Vyāsadevas so far.

At one level, the question about who composed the Mahābhārata is pointless. According to popular belief and according to what the Mahābhārata itself states, it was composed by Kṛṣṇa Dvaipāyana Vedavyāsa (Vyāsadeva). But the text was not composed and cast in stone at a single point in time. Multiple authors kept adding layers and embellishing them. Sections just kept getting added, and it is no one’s suggestion that Kṛṣṇa Dvaipāyana Vedavyāsa composed the text of the Mahābhārata as it stands today.

Consequently, the Mahābhārata is far more unstructured than the Rāmāyaṇa. The major sections of the Rāmāyaṇa are known as kāṇḍas, and one meaning of the word kāṇḍa is the stem or trunk of a tree, suggesting solidity. The major sections of the Mahābhārata are known as parvas, and while one meaning of the word parva is limb or member or joint, in its nuance, there is greater fluidity in the word parva than in kāṇḍa.

The Vyāsadeva we are concerned with had a proper name of Kṛṣṇa Dvaipāyana.

---------------

1. Wealth. But in general, any object of the senses.

2. Desire.

3. Release from the cycle of rebirth.

1.

2.

xix

He was born on an island (द्वीप - dvīpa). That explains the Dvaipāyana part of the name. He was dark. That explains the Kṛṣṇa part of the name. (It was not only the incarnation of Viṣṇu who had the name of Kṛṣṇa.) Kṛṣṇa Dvaipāyana Vedavyāsa was also related to the protagonists of the Mahābhārata story. To go back to the origins, the Rāmāyaṇa is about the solar dynasty, while the Mahābhārata is about the lunar dynasty. As is to be expected, the lunar dynasty begins with Soma (सोम – the moon) and goes down through Purūrava (पुरूरव - who married the famous apsara Urvaśī - उर्वशी), Nahuṣa (नहुष), and Yayāti (ययाति). Yayāti became old but was not ready to give up the pleasures of life. He asked his sons to temporarily loan him their youth. All but one refused. The ones who refused were cursed that they would never be kings, and this includes the Yādavas {descended from Yadu (यदु)}. The one who agreed was Puru, and the lunar dynasty continued through him. Puru’s son Duhshanta (Dushyanta, Duṣyanta - दुष्यन्त) was made famous by Kālidāsa (कालिदास) in the Duṣyanta – Śakuntalā story, and their son was Bharata (भरत), contributing to the name of Bhāratavarṣa (Land of Bhārata). Bharata’s grandson was Kuru. We often tend to think of the Kauravas as the evil protagonists in the Mahābhārata story and the Pāṇḍavas as the good protagonists. Since Kuru was a common ancestor, the appellation Kaurava applies equally to Yudhiṣṭhira and his brothers and Duryodhana and his brothers. Kuru’s Grandson was Śaṃtanu. Through Satyavatī, Śaṃtanu fathers Chitrāngadā (or चित्रांगदा – Chitrangada) and Vicitravīrya (विचित्रवीर्य). However, the sage Parāśara (पराशर) had already fathered Kṛṣṇa Dvaipāyana through Satyavatī. And Śaṃtanu had already fathered Bhīṣma through Gaṅgā (गङ्गा). Dhṛtarāṣṭra and Pāṇḍu were fathered on Vicitravīrya’s wives by Kṛṣṇa Dvaipāyana.

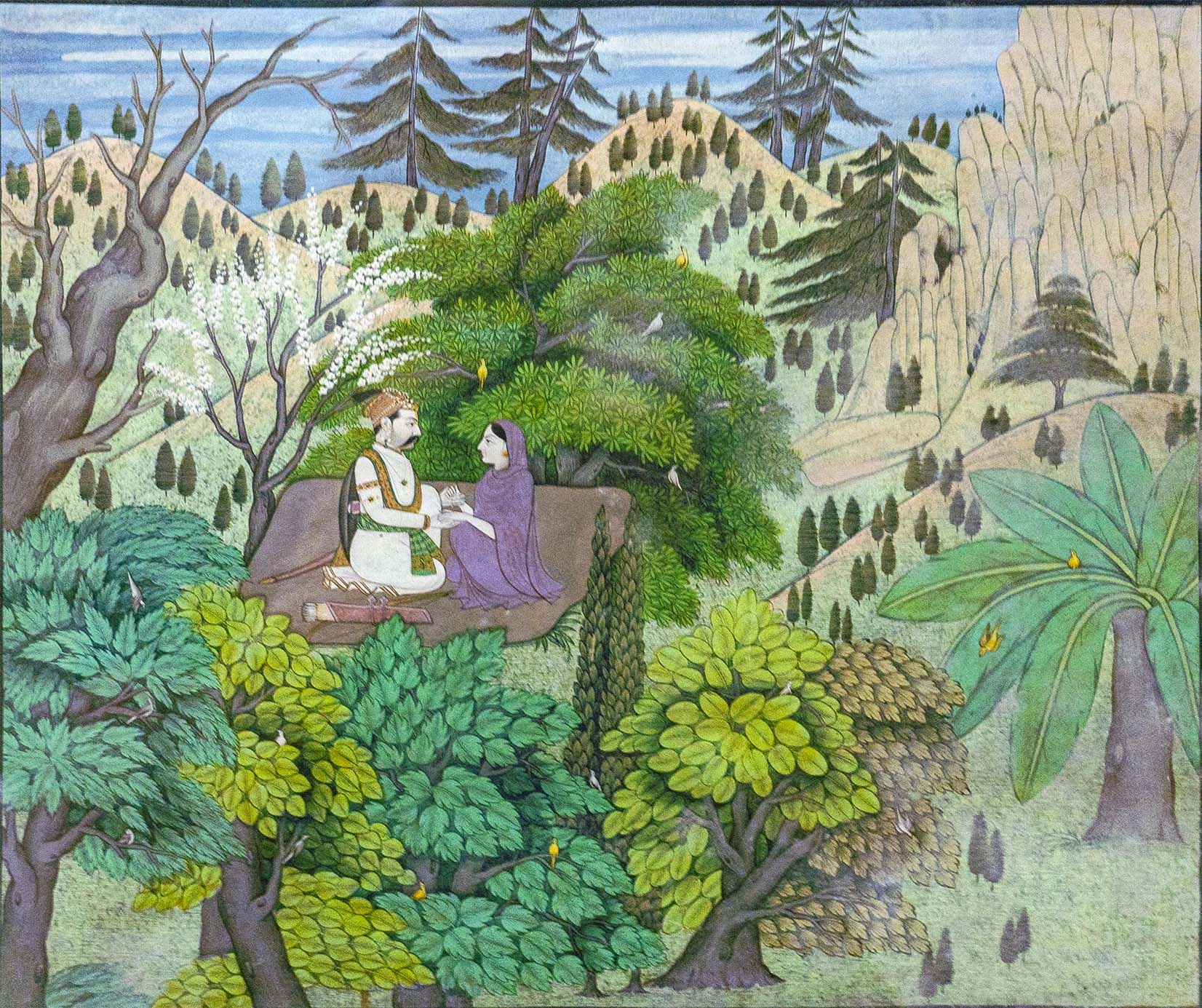

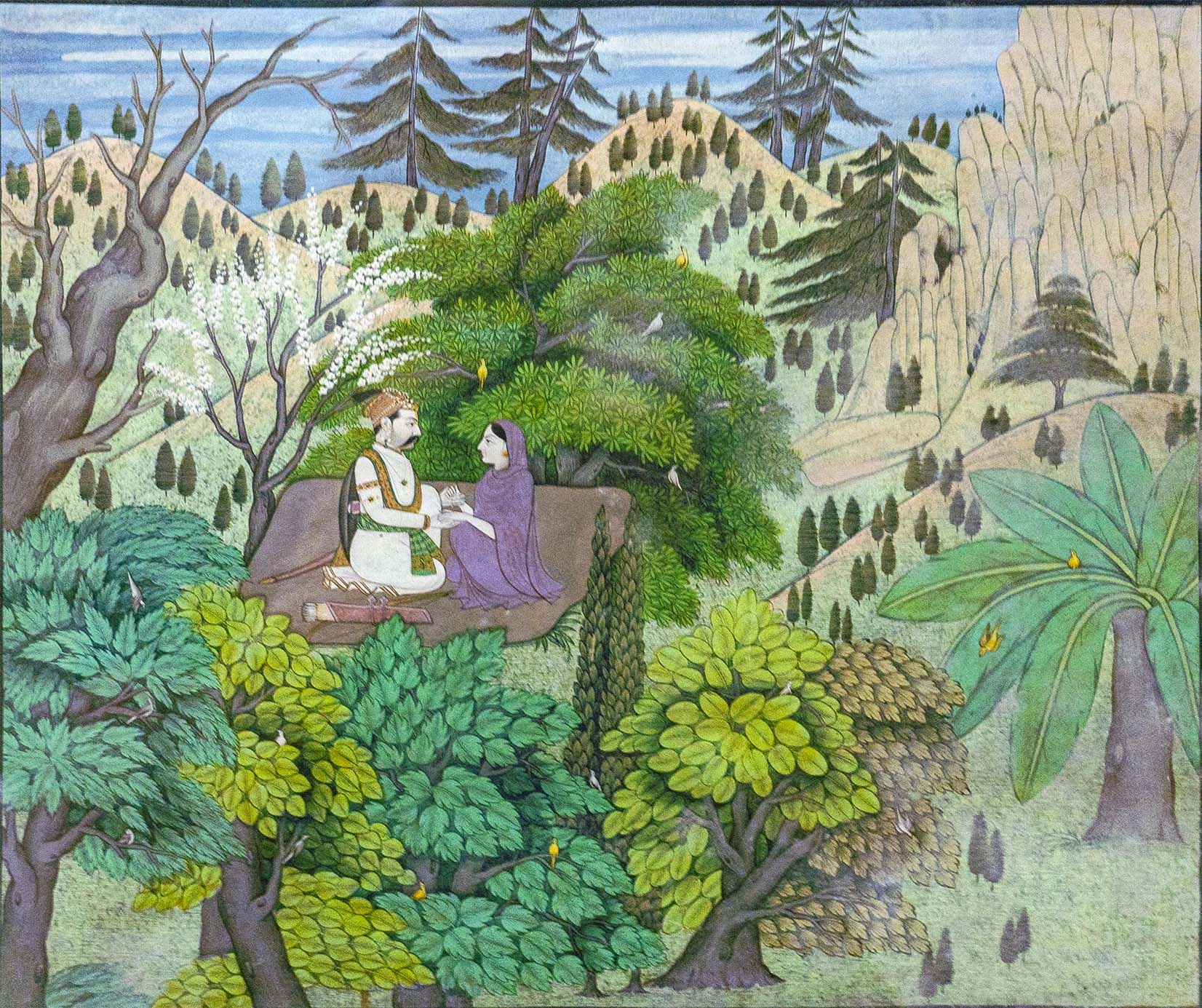

A Paper Painting of Duṣyanta – Śakuntalā, HindurPahari, 1840 CE, New Delhi Museum, Bharat, source: www.wisdomlib.org, access date: November 11, 2025.

A Paper Painting of Duṣyanta – Śakuntalā, HindurPahari, 1840 CE, New Delhi Museum, Bharat, source: www.wisdomlib.org, access date: November 11, 2025.1.

The story of the epic is also about these antecedents and consequents. The core Mahābhārata story is known to every Indian and is normally understood as a dispute between the Kauravas (descendants of Dhṛtarāṣṭra) and the Pāṇḍavas (descendants of Pāṇḍu). However, this is a distilled version, which really begins with Śaṃtanu. The non-distilled version takes us to the roots of the genealogical tree, and at several points along this tree, we confront a problem with impotence/sterility/death, resulting in offspring through a surrogate father. Such sons were accepted in that day and age.

1.

2.

xx

Nor was this a lunar dynasty problem alone. In the Rāmāyaṇa, Daśaratha of the solar dynasty also had an infertility problem, corrected through a sacrifice. To return to the genealogical tree, the Pāṇḍavas won the Kurukṣetra war. However, their five sons through Draupadī were killed. So was Bhīma’s son Ghaṭotkaca, fathered on Hiḍimbā. As was Arjuna’s son Abhimanyu, fathered on Subhadrā. Abhimanyu’s son Parīkṣit inherited the throne in Hāstinapura but was killed by a serpent. Parīkṣit’s son was Janamejaya.

Kṛṣṇa Dvaipāyana Vedavyāsa’s powers of composition were remarkable. Having classified the Vedas, he composed the Mahābhārata in 100,000 ślokas or couplets. Today’s Mahābhārata text does not have that many ślokas, even if the Harivaṃśa (regarded as the epilogue to the Mahābhārata) is included. One reaches around 90,000 ślokas. That, too, is a gigantic number. (The Mahābhārata is almost four times the size of the Rāmāyaṇa and is longer than any other epic anywhere in the world.) For a count of 90,000 Sanskrit ślokas, we are talking about something in the neighbourhood of two million words. The text of the Mahābhārata tells us that Kṛṣṇa Dvaipāyana finished this composition in three years. This does not necessarily mean that he composed 90,000 ślokas. The text also tells us that there are three versions of the Mahābhārata. The original version was called Jaya and had 8,800 ślokas. This was expanded to 24,000 ślokas and called Bhārata. Finally, it was expanded to 90,000 ślokas (or 100,000) ślokas and called Mahābhārata.

Kṛṣṇa Dvaipāyana did not rest even after that. He composed the eighteen Mahā Purāṇas, adding another 400,000 ślokas. Having composed the Mahābhārata, he taught it to his disciple Vaiśaṃpāyana (वैशंपायन). When Parīkṣit was killed by serpents, with all the sages assembled there, Vaiśaṃpāyana turned up and assembled. The sages wanted to know the story of the Mahābhārata, as composed by Kṛṣṇa Dvaipāyana. Janamejaya also wanted to know why Parīkṣit had been killed by the serpent. That’s the background against which the epic is recited. However, there is another round of recounting too. Much later, the sages assembled for a sacrifice in Naimiṣāraṇya and asked Lomaharṣaṇa (alternatively, Romaharṣaṇa) to recite what he had heard at Janamejaya’s snake sacrifice.

1.

2.

xxi

Lomaharṣaṇa was sūta (सूत), the sūtas being charioteers and bards or raconteurs. As the son of a sūta, Lomaharṣaṇa is also referred to as Sauti. But Sauti or Lomaharṣaṇa are not quite his proper names. His proper name is Ugraśrava. Sauti refers to his birth. Hoe owes its name Lomaharṣaṇa to the fact that the body-hair (loma or roma) stood up (harṣaṇa) on hearing his tales. Within the text, therefore, two people are telling the tale. Sometimes it is Vaiśaṃpāyana and sometimes it is Lomaharṣaṇa. Incidentally, the stories of the Purāṇas are recounted by Lomaharṣaṇa, without Vaiśaṃpāyana intruding. Having composed the Purāṇas, Kṛṣṇa Dvaipāyana taught them to his disciple Lomaharṣaṇa. For what it is worth, there are scholars who have used statistical tests to try to identify the multiple authors of the Mahābhārata.

As we are certain there were multiple authors rather than a single one, the question of when the Mahābhārata was composed is somewhat pointless. It was not composed on a single date. It was composed over a span of more than 1,000 years, perhaps between 800 BCE. And 400 ACE. It is impossible to be more accurate than that. There is a difference between dating the composition and dating the incidents, such as the date of the Kurukṣetra war. Dating the incidents is both subjective and controversial and irrelevant for the purposes of this translation. A timeline of 1000 years is not short. But even then, the size of the corpus is nothing short of amazing.

1.

***

1.

Familiarity with Sanskrit is dying out. The first decades of the twenty-first century are quite unlike the first decades of the twentieth. Lamentation over what is inevitable serves a purpose. English is increasingly becoming the global language, courtesy of colonies (North America, South Asia, East Asia, Australia, New Zealand, Africa) rather than the former colonizer. If familiarity with the corpus is not to die out, it needs to be accessible in English.

There are many different versions or recensions of the Mahābhārata. However, between 1919 and 1966, the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute (BORI) in Pune produced what has come to be known as the critical edition.

1.

2.

xxii

This is an authenticated text produced by a board of scholars and seeks to eliminate later interpolations, unifying the text across the various regional versions. This is the text followed in this translation. One should also mention that the critical edition’s text is not invariably smooth. Sometimes, the translation from one śloka to another is abrupt because the intervening śloka has been weeded out. With the intervening śloka included, a non-critical version of the text sometimes makes better sense. On a few occasions, I have had the temerity to point this out in the notes, which I have included in my translation. On a slightly different note, the quality of the text in something like Dāna Dharma Parva is clearly inferior. It could not have been ‘composed’ by the same person.

It took a long time for this critical edition to be put together. The exercise began in 1919. Without the Harivaṃśa, the complete critical edition became available in 1970. Before this, there were regional variations in the text, and the main versions were available from Bengal, Bombay, and the south. However, now, one should stick to the critical edition, though there are occasional instances where there are reasons for dissatisfaction with what the scholars of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute have accomplished. But in all fairness, there are two published versions of the critical edition. The first one has the bare bones of the critical edition’s text. The second has all the regional versions collated, with copious notes. The former is for the ordinary reader, assuming he/she know Sanskrit. And the latter is for the scholar. Consequently, some popular beliefs no longer find a place in the critical edition’s text. For example, it is believed that Vedavyāsa dictated the text to Gaṇeśa, who wrote it down. But Gaṇeśa had a condition before accepting. Vedavyāsa would have to dictate continuously, without stopping. Vedavyāsa threw in a counter-condition. Gaṇeśa would have to understand each couplet before he wrote it down. To flummox Gaṇeśa and give himself time to think, Vedavyāsa threw in some cryptic verses. This attractive anecdote has been excised from the critical edition’s text. Barring material that is completely religious (specific hymns or the Bhagavad Gītā), the Sanskrit text is reasonably easy to understand. Oddly, I have had the most difficulty with things that Vidura has sometimes said, other than parts of Anuśāsana Parva.

1.

2.

xxiii

Arya has today come to connote ethnicity. Originally, it meant language. That is, those who spoke Sanskrit were Aryas. Those who did not speak Sanskrit were mlecchás. Vidura is supposed to have been skilled in the mlecchá language. Is that the reason why some of Vidura’s statements seem obscure? In a similar vein, in popular renderings, when Draupadī is being disrobed, she prays to Kṛṣṇa. Kṛṣṇa provides the never-ending stream of garments that stump Duḥśāsana. The critical edition has excised the prayer to Kṛṣṇa. The never-ending stream of garments is given as an extraordinary event. However, there is no intervention from Kṛṣṇa.

1.

2.

References:

01. from. "The Mahabharata 1," Translated by BIBEK DEBROY, ISBN: 978-0-1434-2514-4, Penguin Random House, 2015, Printed in Bhārat.

02. from. www.wisdomlib.org.

1.

2.

3.