The Great Sage Vālmīki taught the twin "Kuśa & Lava" of Rāma & Sītā, source: bookfact.com, access date: July 24, 2022.

07. Uttara Kanda01,02.

First revision: Jul.23, 2022

Last change: Oct.12, 2023

Searched, Gathered, Rearranged, and Compiled by Apirak Kanchanakongkha.

The Uttarakāṇḍa.

The seventh and final book of Vālmīki’s Rāmāyaṇa, entitled simply the Uttarakāṇḍa, “The Last Book,” is more heterogeneous in its contents and controversial in its reception than any of the epic’s other six books. Of the nature of an extensive epilogue, it contains three general categories of narrative material. The first category includes legends that provide the background, origins, and early careers of some of the outstanding and endlessly fascinating characters in an epic drama whose antecedents were not fully described in the first six books. Interestingly, nearly the entire first half of the book is devoted to a lengthy account of the history and genealogy of the rākṣasas and the early career of Rāvaṇa and, to a much smaller extent, to an understanding of the childhood deeds of Hanumān. In this section, many of the events of the central portion of the epic story are explained as having roots in encounters and curses in the distant past during Rāvaṇa’s wild career of rape, conquest, and carnage.

The bulk of this portion of the text concerns Rāvaṇa’s birth and early years and his many campaigns of world conquest, during which he defeats and assaults many kings, gods, sages, and demons and rapes abducts their womenfolk. Some of the curses he incurs during his wild and violent rampage through the three worlds explain several conditions that face him later on during the lifetime of Rāma. First, he is cursed prenatally by his father to be an evildoer. Subsequently, Vedavatī, a Brahman woman he molests, immolates herself, vowing to be reborn on the day (as Sītā) for his destruction. After he rapes a semidivine woman, her lover curses him to die should he ever again take a woman by force. Similarly, he is cursed by the collectivity of the many women he has abducted to meet his death on account of a woman, and he is cursed by a king of the lineage of the Ikṣvākus – whom he kills – to be himself slain by a future prince (Rāma) of that lineage. Even the destruction of Rāvaṇa’s hosts by powerful, semidivine monkeys is explained by a curse on the part of Lord Śiva’s attendant Nandin, who enraged at Rāvaṇa for mocking him in his simian form, curses him to that effect.

Statue of Rāvaṇa or Dashakanth inside The Emerald Buddha Temple, Bangkok, photo taken on July 2, 2023.

Statue of Rāvaṇa or Dashakanth inside The Emerald Buddha Temple, Bangkok, photo taken on July 2, 2023.

But despite his boon from Brahmā and his long string of conquests, the narrative shows that no one is ultimately invulnerable—the biography of the seemingly invincible. The biography of the seemly invincible rākṣasa ends with two accounts of battles in which he emerges as the loser: he is defeated by the mighty thousand-armed human king Arjuna Kārtavīrya and then also dominated by the powerful monkey king Vālin. These episodes, narrated by the sage Agastya, show that even the mightiest can meet their match and foreshadow Rāvaṇa’s ultimate defeat at the hands of a “mere man,” Rāma. This is all in keeping with Vālmīki’s adherence to the boon of Brahmā, according to which the rākṣasa king would be invulnerable to all supernatural beings but not to humans or animals.

The second category of the Uttarakāṇḍa’s narrative material consists of good myths and legends that are only thematically related to the epic story and its characters. This material is primarily made up of cautionary tales told to or by Rāma to illustrate the dire consequences that occur to monarchs who fail to uphold the duties of kingship strictly. They are placed in the text at the points, as we discuss later, where Rāma has become prey to dejection after feeling obligated by kingly duty to exile his beloved wife, where he is contemplating a sacrifice, and when he visits the ashram of the sage Agastya. These episodes also bolster the poem’s reputation as a textbook on rājadharma, “royal duty,” – a kind of mirror for kings that presents its hero as the model of the ideal monarch.

The last, and in several ways, the most interesting, category of material in the Uttarakāṇḍa directly concerns itself with episodes from the final years of Rāma, his wife, and his brothers. These episodes are interspersed among the largely cautionary tales of the second category mentioned earlier. With struggle, adversity, and sorrow seemingly behind him, Rāma settles down with Sītā to rule in peace, prosperity, and happiness. We see what looks to be the perfect end to a fairy tale or romance as Rāma and his queen begin their long-delayed rule of their utopian kingdom — the legendary, eleven thousand-years Rāmarājya. But as it develops, there is trouble in paradise, and the joy of the hero and heroine is to be tragically brief.

After dismissing his allies in the Lañkān war with due honors and gifts, Rāma, to his delight, learns that his beloved Sītā is pregnant. But now it suddenly comes to his attention that, despite her fire ordeal in Lañkā, the people of Ayodhyā grumble that the king is corrupt and has taken back into his house in his lust for the beautiful queen. This woman has lived in the household of the lecherous Rāvaṇa. They fear that, since a king sets the moral standard for his kingdom, they too will have to put up with misbehavior on the part of their wives.

Fearing a scandal and in strict conformity to what he sees as the stern duty of the sovereign, Rāma, under the pretext of an excursion, banishes the queen despite her pregnancy. However, he knows the spreading rumors about her are false. Abandoned in the wilderness by Lakṣmaṇa, the unfortunate queen is taken in and sheltered in his ashram by none other than the poet-seer Vālmīki. There, she gives birth to twin sons, Lava and Kuśa, who will become the sage’s disciples and the bards who will perform their master’s poetic creation, the Rāmāyaṇa. Rāma’s separation from his beloved wife casts him into deep grief and depression, alleviated only by hearing and telling cautionary tales about the terrible fate of kings who neglect their royal duties.

During Rāma’s otherwise ideal reign, two strange but significant events occur. First, in a kind of mini reprise of the central theme of the epic, Rāma receives a delegation of sages from the region of the Yamunā River. They have come to complain about the depredations of a terrible and monstrous demon called Lavaṇa. Rāma deputes his youngest brother, Śatrughna, who has had almost no active role in the epic, to deal with this assault on dharma, “righteousness.” Śatrughna sets forth and, on his journey, stays over one night in the ashram of Vālmīki – the very night when Sītā gives birth to Lava and Kuśa. He then proceeds to the Yamunā, where, after a fierce battle, he dispatches the monster and finds the prosperous city of Madhurā (Mathurā) in the region of Saurāṣṭra, where he rules as a virtuous king. After twelve years, longing to see his beloved elder brother, he returns to Ayodhyā with his army, once more staying overnight at Vālmīki’s ashram. During this brief visit, he and his troops hear the Rāmāyaṇa beautifully sung by the twin bards. Although Śatrughna is eager to remain at his brother’s side, in keeping with the tenor of the books as a guide for kings, Rāma sternly orders him to return to his kingdom to govern his people righteously.

Shortly after Śatrughna’s departure, there is another troubling incident, this time in the capital city itself. A grieving Brahman father arrives at Rāma’s palace holding his young son's body in his arms. This is particularly troubling as, according to the tradition—stated multiple times in the epic and continuing to be a fundamental element of the legacy of the Rāmāyaṇa – the long period of Rāma’s millennial reign was a true utopia. Thus, all classes of people strictly observed their proper societal duties; wives always obeyed their husbands, and there was no crime, disease, or natural disasters. One point that is stressed repeatedly is that no child predeceased its parents in this paradisiac kingdom. In such a world, the fact that an incredible thing – the death of the Brahman child – has occurred can only mean that some violation of the social and ritual order is taking place and that it is the responsibility of the king to remedy it. Rāma must, therefore, find and punish the transgressor. In this, he is advised by Nārada, the same seer who first told Vālmīki the story of Rāma. Nārada means the king that somewhere in his realm, a śūdra (ศูทร) – that is, a member of the lowest of the four traditional social classes of Brahmanical society – is practicing religious austerities that are exclusively reserved (during that cosmic era, the Tretā Yuga) for the members of the three higher social classes, the so-called “twice-born.”

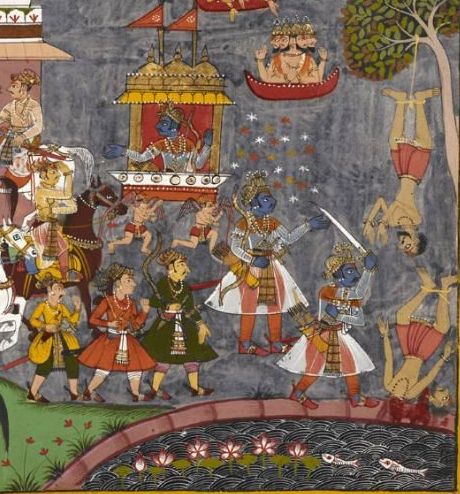

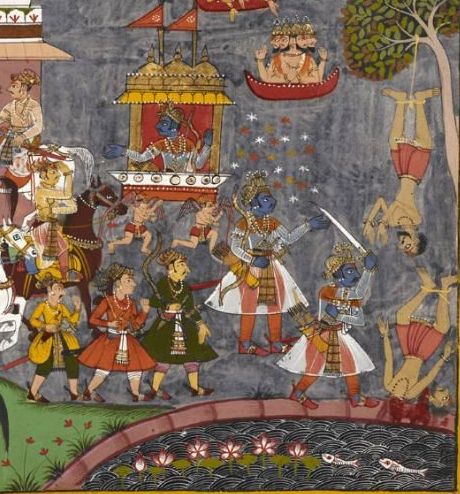

Lord Rāma slays seer Śambūka (The Śūdra Brahmin), Source: sanskritreadingroom.wordpress.com, Access date: Feb.08, 2023.

Lord Rāma slays seer Śambūka (The Śūdra Brahmin), Source: sanskritreadingroom.wordpress.com, Access date: Feb.08, 2023.

Rāma summons and mounts the Puṣpaka, the flying palace he had received from Vibhīṣaṇa, and conducted aerial surveillance of his kingdom. Near the southern border, he finds a man hanging from a tree by his feet. The man says he is practicing austerities to enter heaven in his earthly body. When he identifies himself as Śambūka, a śūdra, Rāma summarily beheads him. When the śūdra dies, the dead Brahman child miraculously returns to life in Ayodhyā. The gods praise Rāma and shower him with heavenly blossoms.

Rāma then pays a brief visit to the ashram of the great sage Agastya, who had narrated the history of the rākṣasas, Rāvaṇa, and Hanumān earlier in the book. There, Rāma hears other cautionary tales about kings and kingdoms that suffered ghastly punishments for failing to follow the code of royal conduct. Rāma then returns to Ayodhyā. Having had a golden image of his banished wife created to serve as her surrogate in the performance of the royal sacrifices, Rāma performs a great aśvamedha, “horse sacrifice.”

During the rite, two handsome young bards appear and begin to recite the Rāmāyaṇa. It turns out that these two, the twins Kuśa and Lava, are the sons of Rāma and Sītā, who have been sheltered for twelve years with their mother in Vālmīki’s ashram. Rāma sends for his beloved queen, intending to take her back. But despite Vālmīki’s attestation of her absolute fidelity, Rāma demands that Sītā take a solemn public oath before the assembled populace. She complies but declares that if she has been faithful to her husband in word, thought, and deed, Mādhavī, the earth goddess, her mother, should receive her. As the ground opens, the goddess emerges on a bejeweled throne, places her long-suffering daughter beside her, and vanishes into the earth.

Consumed by inconsolable grief, Rāma performs sacrifices and rules for many years and sends his brothers out to conquer kingdoms for their sons. At last, urged by a messenger of the gods to resume his proper heavenly form as Lord Viṣṇu, he is forced to banish Lakṣmaṇa, who abandons his earthly body in the Sarayū River. Rāma then divides his kingdom between his sons and, followed by the inhabitants of Ayodhyā and most of his erstwhile allies, enters the waters of the Sarayū and returns to his heavenly abode. These events bring to a close both the book and the epic.

References:

01. from. "The Illustrated Ramayana: The Timeless Epic of Duty, Love, and Redemption," ISBN: 978-0-2414-7376-4, Penguin Random House, 2017, Printed and bound in China, www.dk.com.

02. from. "The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki - THE COMPLETE ENGLISH TRANSLATION," Translated by Robert P. Goldman, Sally J. Sutherland Goldman, Rosalind Lefeber, Sheldon I. Pollock, and Barend A. van Nooten, Revised and Edited by Robert P. Goldman and Sally J. Sutherland Goldman, ISBN 978-0-6912-0686-8, 2021, Princeton University Press, Printed in the United States of America