iii

The Essentials of

Indian Philosophy

M. HIRIYANNA

MOTILAL BANARSIDASS PUBLISHERS

PRIVATE LIMITED ํ DELHI

iv

Reprint: Delhi, 2000, 2005, 2008

First Indian Edition: Delhi; 1995

© M/S KAVYALAYA PUBLISHERS

All Rights Reserved

ISBN : 978-81-208-1304-5 (Cloth)

ISBN : 978-81-208-1330-4 (Paper)

MOTILAL BANARSIDASS

41 U.A. Bungalow Road, Jawahar Nagar, Delhi 110 007

8 Mahalaxmi Chamber, 22 Bhulabhai Desai Road, Mumbai 400 026

203 Royapettah High Road, Mylapore, Chennai 600 004

236, 9th Main III Block, Jayanagar, Bengaluru 560 011

Sanas Plaza, 1302 Baji Rao Road, Pune 411 002

8 Camac Street, Kolkata 700 017

Ashok Rajpath, Patna 800 004

Chowk, Varanasi 221 001

Printed in India

By Jainendra Prakash Jain at Shri Jainendra Press,

A-45, Naraina, Phase-I, New Delhi 110028

and published by Narendra Prakash Jain for

Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Limited,

Bungalow Road, Delhi 110 007

v

Preface

*

IT is now some years since my Outlines of Indian Philosophy was published, with the intention chiefly of providing a handy text-book for students in our universities. A simpler and shorter account of the subject is required for the general reader, and the present attempt is to meet that requirement. It is hoped that the book will be found suitable for the purpose, and that it will receive the same welcome as was generously accorded to its predecessor.

The subject-matter of the two books being identical, there is naturally a certain likeness between them; but it will be seen that no portion of the earlier volume has been verbally reproduced here. The present work, in accordance with the aim kept in view in writing it, leaves out many of the details included in the previous one. The different between them, however, does not consist merely in these omissions: there is also variation in the treatment of some topics, as, for instance, in the first two chapters dealing with early Indian thought. At least in two cases, again, there are important additions. In the earlier book, Buddhism was dealt with in reference to two stages of its growth. There is a third phase, representing the doctrine as it was originally taught by Buddha; and a brief résumé of it, as it has been reconstructed by scholars in recent years, also finds a place here. Similarly, the account of the Vedānta has been amplified by the inclusion of the Dvaita system of it. In treating of such a subject as Indian Philosophy, it is difficult to avoid the use of Sanskrit terms; but their number appearing in the body of the work has been reduced as far as possible, and a Glossary is provided to help the reader in finding out their meanings readily.

I have utilized in the preparation of this book two of my articles contributed to the Aryan Path, and another to the Heritage of Indian Culture (published by the Ramakrishna Mission). I am grateful to the editors of these publications for their courtesy in permitting me to do so. Specific references

vi

to the articles are given at the appropriate places in the Notes appended at the end. I wish to record my feeling of indebtedness to the late Dr. J. E. Turner of the University of Liverpool for his kindness in reading the book in typescript and for his valuable suggestions. Finally, I desire to express my deep gratitude to Professor S. Radhakrishnan for the kindly interest which he has always taken in my work. It is no exaggeration to say that, but for his help and encouragement, neither this book nor the previous one would have been written.

April 1948. M. H.

vii

Contents

Page

PREFACE

|

5

|

| |

I.

|

|

Vedic Religion and Philosophy

|

9

|

| |

II.

|

|

Transition to the System

|

31

|

| |

III.

|

|

Non-Vedic Schools

|

57

|

| |

IV.

|

|

Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika

|

84

|

| |

V.

|

|

Sāṅkhya-Yoga

|

106

|

| |

VI.

|

|

Pūrva-mīmāṁsā

|

129

|

| |

VII.

|

|

Vedānta: Absolutistic

|

151

|

| |

VIII.

|

|

Vedānta: Theistic

|

175

|

| |

NOTES AND REFERENCES |

202 |

| |

SANSKRIT GLOSSARY |

211 |

| |

INDEX |

214 |

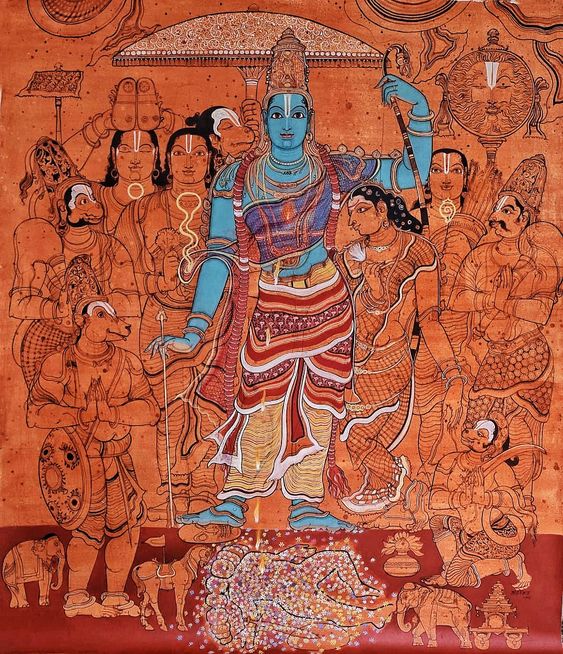

The Paint of Rama holding a bow, source: pinterest.com, access date: Mar.26, 2022.

viii

9 (1)

Chapter One

VEDIC RELIGION AND

PHILOSOPHY

*

THE earliest source of our information regarding Indian thought is the Veda, which signifies, as it has been stated, not a single work but a whole literature. This literature is usually regard as consisting of two parts, viz. Mantras and Brāhmaṇas.1 Several of the early Upanishads are included in the latter; but, on account of their great importance in the history of Indian thought, they deserve to be reckoned as s separate portion of the Veda. Broadly speaking, the three parts mark successive stages in the growth of Vedic literature, and also stand for teachings that are more or less distinct. The determination of the exact chronological limits of these stages is not possible. Even the duration of the Vedic period, as a whole, is not definitely known, though the question has exercised the minds of scholars for long. All that is certain is that the Veda proper, including the chief Upanishads, is older than Buddha, who is known to have died about 480 B.C. The later limit of the Vedic period may accordingly be taken as 500 B.C. As regards the earlier limit, the belief that was generally current till recently, and which has not yet been given up wholly, was 1200-1500 B.C. The view that is now replacing it is the one set forth by Dr. Winternitz in his History of Indian Literature, which fixes the beginning of the period somewhere between 2000 and 2500 B.C. instead of 1200-1500 B.C. It is not known what changes, if any, will be found necessary in this conclusion when the momentous discoveries made in recent years in the Indus valley near Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa are fully understood. These details, however, are not of very much importance for us here. We shall therefore proceed to consider the teaching of the Veda in its triple division.

---------------

1 The Mantras are verse; the Brāhmaṇas are prose, but they often contain quotations in verse. The whole of this material is grouped under four heads, each being designated a “Veda” (i.e. knowledge) – Rigveda, Yajur-veda, Sāma Veda, and Artharva Veda. Each Veda thus includes both Mantras and Brāhmaṇas.

10 (2)

I

The word “mantra” may be regarded as equivalent to a “hymn” or “religious song.” The hymns or religious songs contained in the Veda are of varying age, the oldest of them being separated from the latest by several centuries. They were at a later stage, that is, long after the period of their production, brought together and have been preserved in the form of separate collections (saṁhitā). Two of them, to which we shall occasionally refer in this work, are called the “Rigveda” and the “Atharva Veda.” We do not know what proportion of the sacred songs existing at the time were included in these collections, but we may safely assume that the whole of the material is not found in them. “We have no right to suppose,” says Max Muller, “that we have even a hundredth part of the religious and popular poetry that existed during the Vedic age.”2 We shall, in the present section, take into account only the earlier mantras, postponing the consideration of the later ones to the next section dealing with the Brāhmaṇas to which, in their teaching, they are more akin. We have, however, to remember that several of these early hymns are too obscure to admit of a satisfactory interpretation. This obscurity, together with the incompleteness of the hymn material we possess makes it hard to reach anything like certainty regarding the character of the beliefs which prevailed in that age as a whole. We shall therefore content ourselves with citing here the view now commonly accepted by scholars, that these early mantras inculcate a form of nature worship, and that this religion of nature was, in its essence, transplanted from their original home when the ancestors of the future Aryans immigrated into India.

In this religion the various powers of nature like fire (agni), wind (vāyu) and the sun (sūrya), amidst which man lives and to whose influence he is constantly subject, are personified, the personification implying a belief that the order which is observable in the world, such as the regular succession of seasons or of day and night, is due to the agency of these powers. They are accordingly looked upon as higher beings or gods, whom it is man’s duty to obey and to propitiate. Hence the hymns may generally be described as chants or prayers addressed to

-------------

2 Six Systems of Indian Philosophy (Collected Edition), p.203.

11 (3)

defined powers of nature, regarded as responsible for the governance of the world. The gods thus worshipped are very many. Some of them like Agno, the god of fire, who is represented as the carrier of gifts to the gods, belong to a period anterior to the occupation of India by the Aryans, while others, like Uṣas or “dawn”, worshipped as a goddess and described as a blushing maiden pursued by her lover, the sun, are later creations by them in their new home.3 Although the Vedic pantheon is thus quite large, some deities, as they appear in the hymns that have been preserved, are more important than others. But we may note, by the way, that Śiva and Viṣṇu, the two great gods of later Hinduism, although not unknown to the age, are not among the former. Of the relatively more imposing deities, it will suffice here to refer to two, viz. Varuṇa and Indra. In the words of one of the mantras, they are “the two monarchs that support all living beings.” The distinctive feature of the one is his unswerving adherence to high principles; that of the other, his eagerness to protect his devotees by vanquishing their enemies in battle.

The latter, viz. Indra, is the leading deity of the hymn-collections taken as a whole. He represents mainly valour and force; but he combines with those traits certain others, which one would not like to associate with the idea of the divine. Thus he is vain and boastful, and is uncommonly fond of an intoxicating drink extracted from a creeper called soma. But he seems to have come to hold so exalted a position among the Vedic gods through some accidental circumstance. That circumstance might have been, as indicated by his description as the “protector of the Aryan colour” and as the “destroyer of the dark skin,” the necessity that arose for seeking the aid of a martial and self-assertive deity by the immigrant Aryans in subjugating the hostile tribes who were prior residents of the land which they had invaded. Or it might have been the havoc frequently played by famine

e in their new home, as shown by the description of Indra as the “thunder-god” and as “the liberator of the waters by slaying the demon of drought.” Prof. Radhakrishnan writes, “When the Aryans entered India they found that, as at present, their prosperity was a mere gamble in rain. The rain-god naturally became the national god of the Indo-Aryans.”

---------------

3 “Though the name of Uṣas is radically cognate to Aurora, the cult of Dawn as a goddess is a specially Indian development.” Macdonnell, Vedic Mythology. P.8. p.203.

12 (4)

Indra, however, was not the sole type of divinity known to the Vedic Aryans, for there are clear, though not so frequent, references in these hymns to another important deity, Varuṇa, who is essentially a god of righteousness and is the guardian of all that is worthy and good. He is omniscient, and is described as ever witnessing the truth and falsehood of men-as being “the third whenever two plot in secret.” He is not only able to find out the inmost sin of man, but is also beneficent and will graciously forgive the sinner, if he be truly penitent. “Set us free from the sin we have committed” is, indeed, the burden of every hymn addressed to Varuṇa. The songs composed in his praise are some of the sublimest in the Veda. But to judge from their number in the collections as they have come down to us, he is quite unimportant; and he continued ever after to be so, as shown, for instance, from his position in the later Purāṇic pantheon where he is not the Highest but only a god of the sea – “an Indian Neptune” as he has been styled. He represents probably an earlier ideal, which under the stress of new and changed circumstances like those alluded to above, was superseded by Indra, as the latter also receded to the background in course of time and became but a glorified ruler of the celestial regions. But we should add that it was only the embodiment of the ideal specifically in Varuṇa that was lost and not the ideal itself, for we find it rising into great prominence in later Indian theism.

There is one aspect of the idea of divinity in this period to which we should call particular attention, viz. its intimate association with what is described as ṛta. Ṛta, which etymologically stands for “course,” originally meant “cosmic order,” the maintenance of which, as already stated, is the purpose of all the gods were conceived as preserving the world not merely from physical disorder but also from moral chaos. The one idea is, in fact, implicit in the other; and there is order in the universe, because its control is in righteous hands. Of this principle of righteousness, Varuna is the chief support. He, it has been said, is “the real trustee of the rta.” But the other gods also, not excluding Indra, show it in some degree or other. In fact, “guardians of ṛta” is in Mantras a common epithet of the gods; and all of them are conceived as willing

13 (5)

the right, and seeing to that will being carried out in practice. The word bears a third meaning also in the Veda to which we shall refer later. It has almost ceased to be used in Sanskrit; but we shall see that under the name of dharma, the same idea occupies a very important place in the later Indian views of life also.

According to these early mantras, the world is not only governed by the gods but also owes its existence to them, for it is they who have created it. It is represented as consisting of three parts-heaven, the world of mortals and the intermediate region-each of which has its own guiding divinities. The relation of man to the gods is depicted as one of complete dependence; but it is of quite an intimate kind, for we find Vedic Aryans addressing their gods as “father” and “brother.” The expression of love for the gods, it has been remarked, “is almost a commonplace in Vedic phraseology, as conversely, the gods are represented as fond of the worshipper.”4 Since the gods are the powerful rulers of the universe, man must be devoted to them; and, since they are not merely powerful but are also righteous-minded, he must lead a morally pure life. There is no thought in these Mantras of the physical universe or any aspect of it being unreal. On the other hand, the interest of the people in the everyday world appears then to have been quite keen, for the prayers addressed to the gods are mostly for worldly prosperity-for the grant of sons, cattle and wealth. Not does there yet seem to have arisen any belief in transmigration. But the survival of man after death is recognized. That is to say, the soul is conceived as immortal; and the good and the pious, it is believed, go after death to heaven where they lead a life of perfect joy in the company of the gods. The fate of the souls of the wicked and the impious is not so clearly stated; but they also seem to have been conceived as surviving after death, because they are described, when mentioned at all, as consigned to “abysmal darkness” in contradistinction to the “white light” into which the virtuous pass after death.

---------------

4 Ethics of India, by E. W. Hopkins, p.8. The author adds: “The bhakti or loving devotion, which some scholars imagine to be only a late development of Hindu religion, is already evident in the Rigveda.”

14 (6)

II

We have so far spoken of the earlier hymns, and shall now proceed to consider, within the limits set by our plan, the thought of the later hymns and the Brāhmaṇas. The word, which is derived from brahman meaning “prayer” or “devotion,” signifies an authoritative utterance of a priest, relating particularly to sacrifice; and the Brāhmaṇas are also called because they are the repositories of such utterances. Speaking generally, the thought of the earlier hymns is seen in this period to develop on three lines: monotheism, monism and ritualism. The first two of these, however, are often found mixed up with each other. But the conceptions themselves, as well be explained soon, are quite distinct; and this is the reason for our dealing with them separately.