Title Thumbnail: Acharya M Hiriyanna, Source: https://www.dharmadispatch.in/culture/acharya-m-hiriyanna-the-joyous-radiance-of-sanatana-erudition-and-scholarship, access date: 24 November 2021., Hero Image: The Book Cover.

Outlines of Indian Philosophy 1

First revision: Nov.24, 2021

Last change: Jul.17, 2022

Searched, gathered, rearranged, and examined by Apirak Kanchanakongkha.

OUTLINES OF

INDIAN PHILOSOPHY

M. HIRIYANNA

OUTLINES OF INDIAN PHILOSOPHY

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

ESSENTIALS OF INDIAN PHILOSOPHY

OUTLINES OF

Indian Philosophy

M. HIRIYANNA

MOTILAL BANARSIDASS PUBLISHERS

PRIVATE LIMITED * DELHI

6th Reprint: Delhi, 2018

First Indian Edition: Delhi; 1993

MOTILAL BANARSIDASS PUBLISHER PRIVATE LIMITED

All Rights Reserved

ISBN : 978-81-208-1086-0 (Cloth)

ISBN : 978-81-208-1099-0 (Paper)

MOTILAL BANARSIDASS

41 U.A. Bungalow Road, Jawahar Nagar, Delhi 110 007

1 B, Jyoti Studio Compound, Kennedy Bridge, Nana Chowk, Mumbai 400 007

203 Royapettah High Road, Mylapore, Chennai 600 004

236, 9th Main III Block, Jayanagar, Bengaluru 560 011

8 Camac Street, Kolkata 700 017

Ashok Rajpath, Patna 800 004

Chowk, Varanasi 221 001

Printed in India

By RP Jain at NAB Printing Unit,

A-44, Naraina Industrial Area, Phase I, New Delhi-110028

and published by JP Jain for Motilal Banarsidass Publisher (P) Ltd,

41 U.A. Bungalow Road, Jawahar, Nagar, Delhi-110007

PREFACE

THIS work is based upon the lectures which I delivered for many years at the Mysore University and is published with the intention that it may serve as a text-book for use in colleges where Indian philosophy is taught. Though primarily intended for students, it is hoped that the book may also be of use to others who are interested in the Indian solutions of familiar philosophical problems. Its foremost aim has been to give a connected and, so far as possible within the limits of a single volume, a comprehensive account of the subject ; but interpretation and criticism, it will be seen, are not excluded. After an introductory chapter summarizing its distinctive features, Indian thought is considered in detail in three Parts dealing respectively with the Vedic period, the early post-Vedic period and the age of the systems; and the account given of the several doctrines in each Part generally includes a brief historical survey in addition to an exposition of its theory of knowledge, ontology and practical teaching. Of these, the problem of knowledge is as a rule treated in two sections, one devoted to its psychological and the other to its logical aspect. In the preparation of the book, I have made use of the standard works on the subject published in recent times ; but, except in two or three chapters (e.g. that on early Buddhism), the views expressed are almost entirely based upon an independent study of the original sources. My indebtedness to the footnotes. It was not possible to leave out Sanskrit terms from the text altogether ; but they have been sparingly used and will present no difficulty if the book is read from the beginning and their explanations noted as they are given. To facilitate reference, the number of the page on which a technical expression or an unfamiliar idea is first mentioned is added within brackets whenever it is alluded to in a later portion of the book.

There are two points to which it is necessary to draw attention in order to avoid misapprehension. The view taken

8

here of the Mādhyamika school of Buddhism is that it is pure nihilism, but some are of opinion that it implies a positive conception of reality. The determination of this question from Buddhistic sources is difficult, the more so as philosophic considerations become mixed with historical ones. Whatever the fact, the negative character of its teaching is vouched for by the entire body of Hindu and Jaina works stretching back to times when Buddhism was still a power in the land of its birth. The natural conclusion to be drawn from such a consensus of opinion is that, in at least one important stage of its development in India, the Mādhyamika doctrine was nihilistic; and it was not considered inappropriate in a book on Indian Philosophy to give prominence to this aspect of it. The second point is the absence of any account of the Dvaita school of Vedāntic philosophy. The Vedānta is twofold. It is either absolutistic or theistic, each of which again exhibits many forms. Anything like a complete treatment of its many-sided teaching being out of the question here, only two examples have been chosen-one, the Advaita of Śaṁkara, to illustrate Vedāntic absolutism, and the other, the Viśiṣṭādvaita of Rāmānuja, to illustrate Vedāntic theism.

I have, in conclusion, to express my deep gratitude to Sir S. Radhakrishnan, Vice-Chancellor of the Andhra University, who has throughout taken a very kindly and helpful interest in this work, and to Mr. D. Venkataramiah of Bangalore, who has read the whole book and suggested various improvements.

M. H.

August 1932

CONTENTS

| |

CHAPTER |

PAGE |

| |

|

INTRODUCTION |

13 |

| |

PART I |

| |

VEDIC PERIOD |

| |

I. |

PRE-UPANIṢADIC THOUGHT |

29 |

| |

II. |

THE UPANISADS |

48 |

| |

PART II |

| |

EARLY POST-VEDIC PERIOD |

| |

III. |

GENERAL TENDENCIES |

87 |

| |

IV. |

BHAGAVAGĪTĀ |

116 |

| |

V. |

EARLY BUDDHISM |

133 |

| |

VI. |

JAINISM |

155 |

| |

PART III |

| |

AGE OF THE SYSTEMS |

| |

VII. |

PRELIMINARY |

177 |

| |

VIII. |

MATERIALISM |

187 |

| |

IX. |

LATER BUDDHISTIC SCHOOLS |

196 |

| |

X. |

NYĀYA-VAIŚEṢIKA |

225 |

| |

XI. |

SĀŃKHYA-YOGA |

267 |

| |

XII. |

PŰRVA-MĪMĀṀSĀ |

298 |

| |

XIII. |

VEDĀNTA. (A) ADVAITA |

336 |

| |

XIV. |

VEDĀNTA. (B) VIŚIṢṬĀDVAITA |

383 |

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

INDEX |

413 |

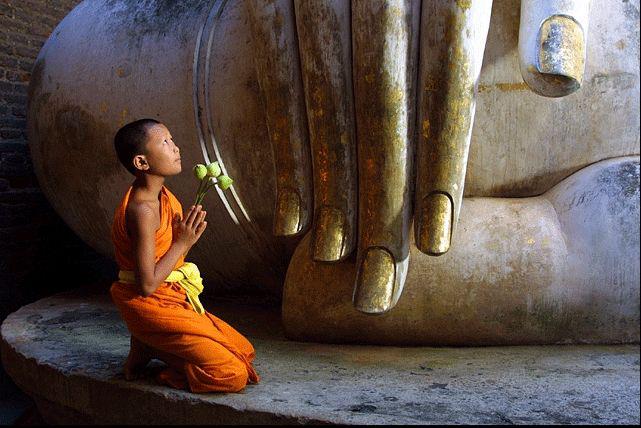

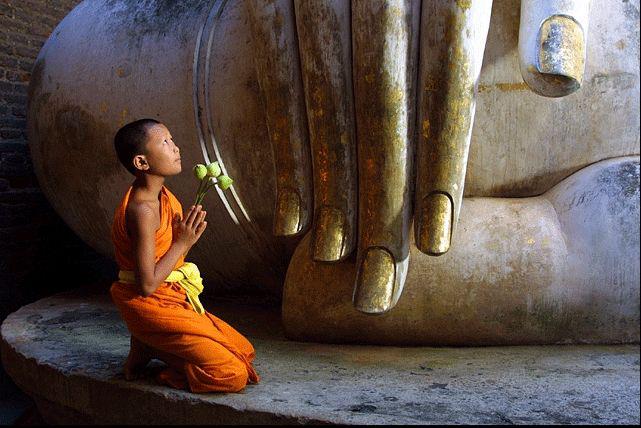

source: yogaenred.com, access date: 08 December 2021.

ABBREVIATIONS

| |

ADS. |

Āpastamba-dharma-sūtra (Mysore Oriental Library Edn.). |

| |

AV. |

Atharva-Veda. |

| |

BG. |

Bhagavadgītā. |

| |

BP. |

Buddhistic Philosophy by Prof. A. B. Keith (Camb. Univ. Press). |

| |

Bṛ.Up. |

Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad. |

| |

BUV. |

Bṛhadāraṇyakopaniṣad-vārtika by Sureśvara. |

| |

Ch.Up. |

Chāndogya Upaniṣad. |

| |

EI. |

Ethics of India by Prof. E. W. Hopkins. |

| |

ERE. |

Encyclopædia of Religion and Ethics. |

| |

GDS. |

Gautama-dharma-sutra (Mysore Oriental Library Edn.). |

| |

IP. |

Indian Philosophy by Prof. S. Radhakrishnan: 2 vols. |

| |

JAOS. |

Journal of the American Oriental Society. |

| |

Mbh. |

Mahābhārata. |

| |

NM. |

Nyāya-mañjarī by Jayanta Bhaṭṭa (Vizianagaram Sans. Series). |

| |

NS. |

Nyāya-sūtra of Gautama (Vizianagaram Sans. Series). |

| |

NSB. |

Nyāya-sūtra-bhāṣya by Vātsyāyana (Vizianagaram Sans. Series). |

| |

NV. |

Nyāya-vārtika by Uddyotakara (Chowkhamba Series). |

| |

OJ. |

Outlines of Jainism by J. Jaini (Camb. Univ. Press). |

| |

OST. |

Original Sanskrit Texts by J. Muir. 5 vols. |

| |

VB. |

Vaiśeṣika-sūtra-bhāṣya by Praśastapāda (Vizianagaram Sans. Series). |

| |

PP. |

Prakaraṇa-pañcikā by Śalikanātha (Chowkhamba Series). |

| |

PU. |

Philosophy of the Upaniṣads by P. Deussen: Translated into English by A. S. Geden. |

| |

Rel. V. |

Religion of the Veda by Maurice Bloomfield. |

| |

RV. |

Ṛgveda. |

| |

SAS. |

Sarvārtha-siddhi with Tattva-muktā-Kalāpa by Vedānta Deśika (Chowkhamba Series). |

| |

SB. |

Śri-bhāṣya by Rāmānuja with Śruta-prakāśikā: Sūtras 1-4. (Nirṇaya Sāg. Pr.). |

| |

SBE. |

Sacred Books of the East. |

12

| |

SD. |

Śastra-dīpikā by Pārthasārathi Miśra with Yukti-sneha-prapūraṇi (Nirṇaya Sāg. Pr.). |

| |

SDS. |

Sarva-darśana-saṁgraha by Mādhava (Calcutta), 1889. |

| |

SK. |

Sāṅkhya-Kārikā by Iśvarakṛṣṇa. |

| |

SLS. |

Siddhānta-leśa-saṁgraha by Appaya Dīkṣita (Kumbha-konam Edn.). |

| |

SM. |

Siddhānta-muktāvalī with Kārikāvalī by Visvanatha: (Nirṇaya Sāg. Pr.), 1916. |

| |

SP. |

Sāṅkhya-pravacana-sūtra. |

| |

SPB. |

Sāṅkhya-pravacana-bhāṣya by Vijñāna Bhikṣu. |

| |

SS. |

Six Systems of Indian Philosophy by F. Max Müller (Collected Works, vol. XIX). |

| |

STK. |

Sāṅkhya-tattva-kaumudī by Vācaspati Miśra. |

| |

SV. |

Śloka-vārtika by Kumārila Bhaṭṭa (Chowkhamba Series). |

| |

TS. |

Tarka-saṁgraha by Annaṁbhaṭṭa (Bombay Sanskrit Series). |

| |

TSD. |

Tarka-saṁgraha-dīpikā (Bombay Sanskrit Series). |

| |

VAS. |

Vedārtha-saṁgraha by Rāmānuja with Tātparya- dīpikā. (Chowkhamba Series), 1894. |

| |

VP. |

Vedānta-paribhāṣā by Dharmarāja Adhvarīndra (Veṅkate-śvara Press, Bombay). |

| |

VS. |

Vedānta-sūtra by Bādarāyaṇa. |

| |

YS. |

Yoga-sūtra by Patañjali. |

| |

YSB. |

Yoga-sūtra- bhāṣya by Vyāsa. |

INTRODUCTION

THE beginnings of Indian philosophy take us very far back indeed, for we can clearly trace them in the hymns of the Ṛgveda which were composed by the Aryans not long after they had settled in their new home about the middle of the second millennium before Christ. The speculative activity begun so early was continued till a century or two ago, so that the history that we have to narrate in the following pages covers a period of over thirty centuries. During this long period, Indian thought developed practically unaffected by outside influence; and the extent as well as the importance of its achievements will be evident when we mention that it has evolved several systems of philosophy, besides creating a great national religion – Brahminism, and a great world religion – Buddhism. The history of so unique a development, if it could be written in full, would be of immense value; but our knowledge at present of early India, in spite of the remarkable results achieved by modern research, is too meagre and imperfect for it. Not only can we not trace the growth of single philosophic ideas step by step; we are sometimes unable to determine the relation even between one system and another. Thus it remains a moot question to this day whether the Sāṅkhya represents an original doctrine or is only derived from some other. This deficiency is due as much to our ignorance of significant details as to an almost total lack of exact chronology in early Indian history. The only date that can be claimed to have been settled in the first one thousand years of it, for example, is that of the death of Buddha, which occurred in 487 B.C. Even the dates we know in the subsequent portion of it are for the most part conjectural, so that the very limits of the periods under which we propose to treat of our subject are to be regarded as tentative. Accordingly our account, it will be seen, is connection we may also perhaps refer to another of its drawbacks which is sure to strike a student who is familiar

14

with Histories of European philosophy. Our account will for the most part be devoid of references to the lives or character of the great thinkers with whose teaching it is concerned, for very little of them is now known. Speaking of Udayana, an eminent Nyaya thinker, Cowell wrote:1 ‘He shines like one of the fixed stars in India’s literary firmament, but no telescope can discover any appreciable diameter; his name is a point of light, but we can detect therein nothing that belongs to our earth or material existence.’ That description applies virtually to all who were responsible for the development of Indian thought; and even a great teacher like Śaṁkara is to us now hardly more than a name. It has been suggested2 that this indifference on the part of the ancient Indians towards the personal histories of their great men was due to a realization by them that individuals are but the product of their times - ‘that they grow from a soil that is ready-made for them and breathe an intellectual atmosphere which is not of their own making.’ It was perhaps not less the result of the humble sense which those great men had of themselves. But whatever the reason, we shall miss in our account the biographical background and all the added interest which it signifies.

If we take the date given above as a landmark, we may divide the history of Indian thought into two stages. It marks the close of Vedic period3 and the beginning of what is known as the Sanskrit or classical period. To the former belong the numerous works that are regarded by the Hindus as revealed. These works, which in extent have been compared to ‘what’ survives of the writings of Ancient Greece,’ were collected in the latter part of the period. If we overlook the changes that should have crept into them before they were thus brought together, they have been

---------------

1 Introduction to Kusumāñjali (Eng. Translation), pp. v and vi.

2 SS. p. 2.

3 It is usual to state the lower limit of the Vedic period as 200 B.C., including within it works which, though not regarded as ‘revealed’ (śrutī), are yet exclusively concerned with the elucidation of revealed texts. We are here confining the term strictly to the period in which Vedic works appeared.

15

preserved, owing mainly to the fact that they were held sacred, with remarkable accuracy; and they are consequently far more authentic than any work of such antiquity can be expected to be. But the collection, because it was made chiefly, as we shall see, for ritualistic purposes, is incomplete and therefore fails to give us a full insight into the character of the thoughts and beliefs that existed then. The works appear in it arranged in a way, but the arrangement is not such as would be of use to us here; and the collection is from our present standpoint to be viewed as a yet more extensive literature; and, since new manuscripts continue to be discovered, additions to it are still being made. The information it furnishes is accordingly fuller and more diverse. Much of this material also appears in a systematized form. But this literature cannot always be considered quite as authentic as the earlier one, for in the course of long oral transmission, which was once the recognized mode of handing down knowledge, many of the old treatises among them even in their original form, do not carry us back to the beginning of the period. Some of them are undoubtedly very old, but even they are not as old as 500 B.C., to state that limit in round numbers. It means that the post-Vedic period is itself to be split up into two stages. If for the purpose of this book we designate the later of them as ‘the age of the systems,’ we are left with an intervening period which for want of a better title may be described as ‘the early post-Vedic period.’ Its duration is not precisely determinable, but it lasted sufficiently long-from 500 B.C. to about the beginning of Christian Era – to be viewed as a distinct stage in the growth of Indian thought. It marks a transition and its literatures of the preceding and of the succeeding periods. While it is many-sided and not fully authentic like its successor, it is unsystematized like its predecessor.

Leaving the details of our subject, so far as they fall within the scope of this work, to be recounted in the following

16

chapters, we may devote the present to a general survey of it. A striking characteristic of Indian thought is its richness and variety. There is practically no shade of speculation which it does not include. This is a matter that is often lost sight of by its present-day critic who is fond of applying to it sweeping epithets like ‘negative’ and ‘pessimistic’ which, though not incorrect so far as some of its phases are concerned, are altogether misleading as descriptions of it as a whole. There is, as will become clear when we study our subject in its several stages of growth, no lack of emphasis on the reality of the external world or on the optimistic view of life understood in its larger sense. The misconception is largely due to the partial knowledge of Indian thought which hitherto prevailed; for it was not till recently that works on Indian philosophy, which deal with it in anything like a comprehensive manner, were published. The schools of thought familiarly known till then were only a few ; and even in their case, it was forgotten that they do not stand for a uniform doctrine throughout their history, but exhibit important modifications rendering such wholesale descriptions of them inaccurate. The fact is that Indian thought exhibits such a diversity of development that it does not admit of a rough-and-ready characterization. Underlying this varied development, there are two divergent currents clearly discernible-one having its source in the Veda and the other, independent of it. We might describe them as orthodox and heterodox respectively, provided we remember that these terms are only relative and that either school may designate the other as heterodox, claiming for itself the ‘halo of orthodoxy.’ The second against the first; but it is not much later since it manifests itself quite early as shown by references to it even in the Vedic hymns. It appears originally as critical and negative; but it begins before long to develop a constructive side which is of great consequence in the history of Indian philosophy. Broadly speaking, it is pessimistic and realistic. The other doctrine cannot be described thus briefly, for even in its earliest recorded phase it presents a very complex

17

character. While for example the prevailing spirit of the songs included in the Ṛgveda is optimistic, there is sometimes a note of sadness in them as in those addressed to the goddess of dawn (Uṣas), which pointedly refer to the way in which she cuts short the little lives of men. ‘Obeying the behests of the gods, but wasting away the lives of mortals, Uṣas has shone forth-the last of many former dawns and the first of those that are yet to come.’1 The characteristic marks of the two currents are, however, now largely obliterated owing to the assimilation or appropriation of contact; but the distinction itself has not disappeared and can be seen in the Vedānta and Jainism, both of which are still living creeds.

These two types of thought, though distinct in their origin and general spirit, exhibit certain common features. We shall dwell at some length upon them, as they form the basic principles of Indian philosophy considered as a whole:-

(i) The first of them has in recent times become the subject of a somewhat commonplace observation, viz. that religion and philosophy do not stand sundered in India. They indeed begin as one everywhere, for their purpose is in the last resort the same, viz. a seeking for the central meaning of existence. But soon they separate and develop on more or less different lines. In India also the differentiation take place, but only it does not mean divorce. This result has in all probability been helped by the isolated development of Indian thought already referred to,2 and has generally been recognized as a striking excellence of it. But owing to the vagueness of the word ‘religion,’ we may easily miss the exact significance of the observation. This word, as it is well known, may stand for anything ranging from what has been described as ‘a sum of scruples which impede

---------------

1 Cf. RV. I. 124. 2.

2 We may perhaps instance as a contrast the course which thought has taken in Europe, where the tradition of classical culture, which is essentially Indo-European, has mingled with a Semitic creed. Mrs. Rhys Davids speaks of science, philosophy and religion as being ‘in an armed truce’ in the West. See Buddhism (Home University Library), p. 100.

18

the free use of our faculties’ to yearning of the human spirit for union with God. It is no praise to any philosophy to be associated with religion in the former sense. Besides, some Indian doctrines are not religion at all in the commonly accepted sense. For example, early Buddhism was avowedly atheistic and it did not recognize any permanent spirit. Yet the statement that religion and philosophy have been one in India is apparently intended to be applicable to all the doctrines. So it is necessary to find out in what sense of the word the observation in question is true. Whatever else a religion may or may not be, it is essentially a reaching forward to an ideal, without resting in mere belief or outward observances. Its distinctive mark is that it serves to further right living; and it is only in this sense that we can speak of religion as one with philosophy in India.1 The ancient Indian did not stop shirt at the discovery of truth, but strove to realize it in his own experience. He followed up tattva-jñāna, as it is termed, by a strenuous effort to attain mokṣa or liberation,2 which therefore, and not merely an intellectual conviction, was in his view the real goal of philosophy. In the words of Max Muller, philosophy was recommended in India ‘not for the sake of knowledge, but for the highest purpose that man can strive after in this life.'3 The conception of mokṣa varies from system to system; but it marks, according to all, the culmination of philosophic culture. In other words, Indian philosophy aims beyond Logic. This peculiarity of the view-point is to be ascribed to the fact that philosophy in India did not take its rise in wonder or curiosity as it seems to have done in the West; rather it originated under the pressure of a practical need arising from the presence of moral and physical evil in life. It is the problem of how to remove this evil that troubled the ancient Indian most, and mokṣa in all the systems represents a state in which it is, in one sense or another, taken to have been overcome. Philosophic endeavour was directed primarily

---------------

1 Indian philosophy may show alliance with religion in other sense also, but such alliance does not form a common characteristic of all the doctrines.

2 Cf. NS. I. i. I.

3 SS. P. 370.

19

to find a remedy for the ills of life, and the consideration of metaphysical questions came in as a matter of course. This is clearly indicated for instance by the designation – sometimes applied to the founders of the several schools – of ‘Tīrtha-kara’ or ‘Tīrthaṁ-kara,’ which literally means ‘ford-maker’ and signifies one that has discovered the way to the other shore across the troubled ocean of saṁsāra.

But it may be thought that the idea of mokṣa, being eschatological, rests on mere speculation and that, though it may be regarded as the goal of faith, it can hardly be represented as that of philosophy. Really, however, there is no ground for thinking so, for, thanks to the constant presence in the Indian mind of a positivistic standard, the mokṣa ideal, even in those schools in which it was not so from the outset, speedily came to be conceived as realizable in this life, and described as jīvan-mukti, or emancipation while yet alive. It still remained, no doubt, a distant ideal; but what is important to note is that it ceased to be regarded as something to be reached in a life beyond. Man’s aim was no longer represented as the attainment of perfection in a hypothetical hereafter, but as a continual progress towards it within the limits of the present life.