The Six Systems of Indian Philosophy 1

First revision: Jan.26, 2022

Last change: Apr.13, 2022

Searched, Gathered, Rearranged, and Examined by Apirak Kanchanakongkha.

The Six Systems of Indian

Philosophy

MAX MÜLLER

COLLECTION WORKS

OF

THE RIGHT HON, F. MAX MÜLLER

XIX

THE SIX SYSTEMS OF INDIAN PHILOSOPHY

THE SIX SYSTEMS

OF

INDIAN PHILOSOPHY

BY THE

RIGHT HON. PROFESSOR MAX MÜLLER, K.M.

LATE FOREIGN MEMBER OF THE FRENCH INSTITUTE

NEW IMPRESSION

LONGMANS, GREEN AND CO.

39 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON

FOURTH AVENUE & STREET, NEW YORK

BOMBAY, CALCUTTA, AND MADRAS

1919

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTE.

First printed 8vo, June, 1899.

New Edition, Cr. 8vo, in the Collected Edition of

Prof. Max Müller’s Works, October, 1903.

Reprinted, January, 1912; March, 1916 ; September, 1919.

v

PREFACE

IT is not without serious misgivings that I venture at this late hour of life to place before my fellow-workers and all who are interested in the growth of philosophical thought throughout the world. some of the notes on the Six Systems of Indian Philosophy which have accumulated in my note-books for many years. It was as early as 1852 that I published my first contributions to the study of Indian philosophy in the Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft. My other occupations, however, and, more particularly, my preparations for a complete edition of the Rig-Veda, and its voluminous commentary, did not allow me at that time to continue these contributions, though my interest in Indian philosophy, as a most important part of the literature of India and of Universal Philosophy, has always remained the same. This interest was kindled afresh when I had to finish for the Sacred Books of the East (vols. I and XV) my translation of the Upanishads, the remote sources of Indian philosophy, and especially of the Vedānta-philosophy, a system in which human speculation seems to me to have reached its very acme. Some of the other systems of Indian philosophy also have from time to time roused the curiosity of scholars and philosophers in Europe and America, and in India itself a revival of philosophic and theosophic studies, though not always well directed, has taken place, which, if it leads to a more active co-operation between European and Indian

vi

thinkers, may be productive in the future of most important results. Under these circumstances a general desire has arisen, and has repeatedly been expressed for the publication of a more general and comprehensive account of the six systems in which the philosophical thought of India has found its full realisation.

Professor Paul Jakob Deussen, (1845-1919) Author of The Philosophy of the Upanishads, Source: librarything.com, access date: March 1, 2022.

Richard Von Garbe (9 March 1857 - 22 September 1927), German Indologist and librarian, source: wikidata.org, access date: 3 March 2022.

More recently the excellent publications of Professors Deussen and Garbe in Germany, and of Dr. G. Thibaut in India, have given a new impulse to these important studies, important not only in the eyes of Sanskrit scholars by profession, but of all who wish to become acquainted with all the solutions which the most highly gifted races of mankind have proposed for the eternal riddles of the world. These studies, to quote the words of a high authority, have indeed ceased to be the hobby of a few individuals, and have become a subject of interest to the whole nation1. Professor Deussen’s work on the Vedānta-philosophy (1883) and his translation of the Vedānta-Sūtras (1887), Professor Garbe’s translation of Sāmkhya-Sūtras (1889) followed by his work on the Sāmkhya-philosophy (1894), and, last not least, Dr. G. Thibaut’s careful and most useful translation of the Vedānta-Sūtras in vols. XXXIV and XXXVIII of the Sacred Books of the East (1890 and 1896), mark a new era in the study of the two most important philosophical systems of ancient India, and have deservedly placed the names of their authors in the front rank of Sanskrit scholars in Europe.

My object in publishing the results of my own studies in Indian philosophy was not so much to restate the mere tenets of each system, so deliberately and so clearly put forward by the reputed authors of the principal philosophies of India, as to give a more comprehensive account of the

---------------

1 Words of Viceroy of India, see Times, Nov.8, 1898.

vii

philosophical activity of the Indian nation from the earliest times, and to show how intimately not only their religion, but their philosophy also, was connected with the national character of the inhabitants of India, a point of view which has of late been so ably maintained by Professor Knight of St. Andrews University1.

It was only in a country like India, with all its physical advantages and disadvantages, that such a rich development of philosophical thought as we can watch in the six systems of philosophy, could have taken place. In ancient India there could hardly have been taken place. In ancient India there could hardly have been a very severe struggle for life. The necessaries of life were abundantly provided by nature, and people with few tastes could live there like the birds in a forest, and soar like birds towards the fresh air of heaven and the eternal sources of light and truth. What was there to do for those who, in order to escape from the heat of tropical sun, had taken their abode in the shade of groves or in the caves of mountainous valleys, except to meditate on the world in which they found themselves placed, they did not know how or why? There was hardly any political life in ancient India, such as we know it from the Vedas, and in consequence neither political strife nor municipal ambition. Neither art nor science existed as yet, to call forth the energies of this highly gifted race. While we, overwhelmed with newspapers, with parliamentary reports, with daily discoveries and discussions, with new novels and time-killing social functions, have hardly any leisure left to dwell on metaphysical and religious problems, these problems formed almost the only subject on which the old inhabitants of India could spend their intellectual energies. Life in a forest was no impossibility in the warm climates of India,

---------------

1 See ‘Mind,’ vol. v. no. 17.

viii

and in the absence of the most ordinary means of communication, what was there to do for the members of the small settlements dotted over the country, but to give expression to that wonder at the world which is the beginning of all philosophy? Literary ambition could hardly exist during a period when even the art of writing was not yet known, and when there was no literature except what could be spread and handed down by memory, developed to an extraordinary and almost incredible extent under a carefully elaborated discipline. But at a time when people could not yet think of public applause or private gain, they thought all the more of truth; and hence the perfectly independent and honest character of most of their philosophy.

It has long been my wish to bring the results of this national Indian philosophy nearer to us, and, if possible, to rouse our sympathies for their honest efforts to throw some rays of light on the dark problems of existence, whether of the objective world at large, or of the subjective spirits, whose knowledge of the world constitutes, after all, the only proof of the existence of an objective world. The mere tenets of each of the six systems of Indian philosophy are by this time well known, or easily accessible, more accessible, I should say, than even those of the leading philosophers of Greece or of modern Europe. Every one of the opinions at which the originators of the six principal schools of Indian philosophy arrived, has been handed down to us in the form of short aphorisms or Sūtras, so as to leave but little room for uncertainty as to the exact position which each of these philosophers occupied on the great battlefield of thought. We know what an enormous amount of labour had to be spent and is still being spent in order to ascertain the exact views of Plato and Aristotle, nay,

ix

even of Kant and Hegel, on some of the most important questions of their systems of philosophy. There are even living philosophers whose words often leave us in doubt as to what they mean, whether they are materialists or idealists, monists or dualists, theists or atheists. Hindu philosophers seldom leave us in doubt on such important points, and they certainly never shrink from the consequences of their theories. They never equivocate or try to hide their opinions where they are likely to be unpopular.

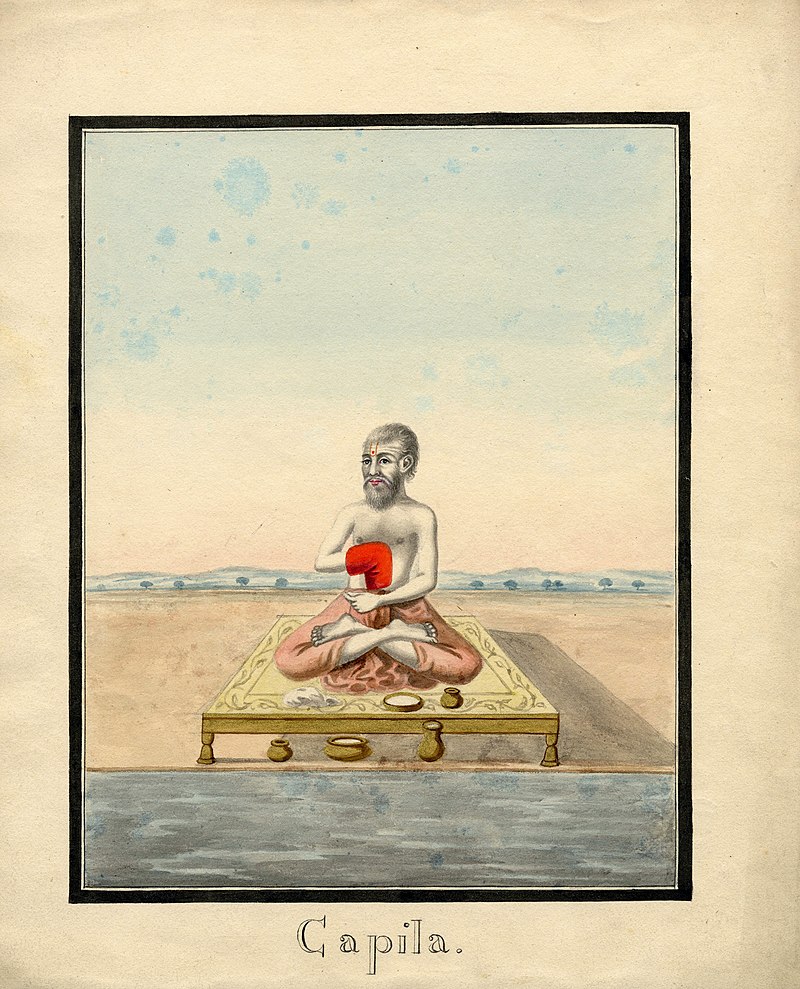

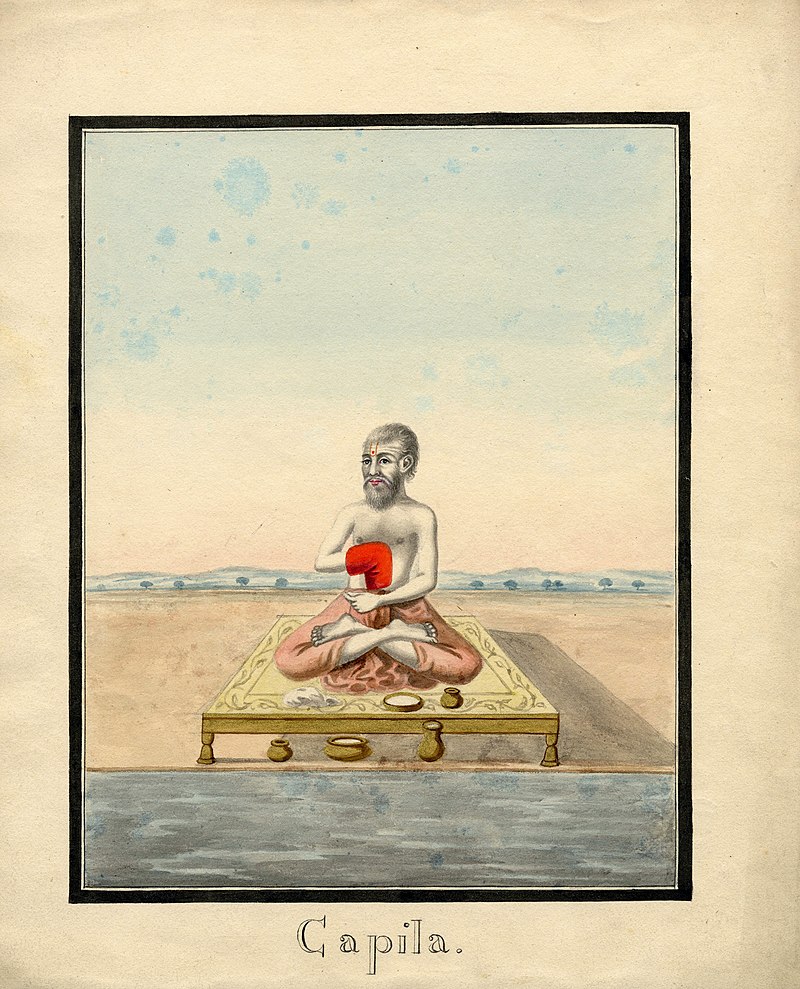

Watercolor painting on paper of Kapila, a sage, source: en.wikipedia.org, access date: Mar.31, 2022.

Watercolor painting on paper of Kapila, a sage, source: en.wikipedia.org, access date: Mar.31, 2022.

Kapila, for instance, the author or hero eponymus of the Sāmkhya-philosophy, confesses openly that his system is atheistic, an īsvara, without an active Lord or God, but in spite of that, his system was treated as legitimate by his contemporaries, because it was reasoned out consistently, and admitted, nay, required some transcendent and invisible power, the so-called Purushas. Without them there would be no evolution of Prakriti, original matter, no objective world, nor any reality in the lookers-on themselves, the Purushas or spirits. Mere names have acquired with us such a power that the authors of systems in which there is clearly no room for an active God, nevertheless shrink from calling themselves atheists, nay, try even by any means to foist an active God into their philosophies, in order to escape the damaging charge of atheism. This leads to philosophical ambiguity, if not dishonesty, and has often delayed the recognition of a Godhead, free from all the trammels of human activity and personality, but yet endowed with wisdom, power, and will. From a philosophical point of view, no theory of evolution, whether ancient or modern (in Sanskrit Parināma), can provide any room for a creator or governor of the world, and hence the Sāmkhya-philosophy declares itself fearlessly as an-īsvara, Lord-less, leaving it to another philosophy, the Yoga, to

x

find in the old Sāmkhya system some place for an Īsvara or a personal God. What is most curious is that a philosopher, such as Samkara, the most decided monist, and the upholder of Brahman, as a neuter, as the cause of all things, is reported to have been a worshipper of idols and to have seen in them, despite of all their hideousness, symbols of the Deity, useful, as he thought, for the ignorant, even though they have no eyes as yet to see what is hidden behind the idols, and what was the true meaning of them.

What I admire in Indian philosophers is that they never try to deceive us as to their principles and the consequences of their theories. If they are idealists, even to the verge of nihilism, they say so, and if they hold that the objective world requires a real thought not necessary a visible or tangible substratum, they are never afraid to speak out. They are bona fide idealists or materialists, monists or dualists, theists or atheists, because their reverence for truth is stronger than their reverence for anything else. The Vadāntist, for instance, is a fearless idealist, and, as a monist, denies the reality of anything but the One Brahman, the Universal Spirit, which is to account for the whole of the phenomenal world. The followers of the Sāmkhya, on the contrary, though likewise idealists and believers in an unseen Purusha (subject), and an unseen prakriti (Objective substance), leave us in no doubt that they are and mean to be atheists, so far as the existence of an active God, maker and ruler of the world, is concerned. They do not allow themselves to be driven one inch beyond their self-chosen position. They first examine the instruments of knowledge which man possesses. These are sensuous perception, inference, and verbal authority, and as none of these can supply us with the knowledge of a Supreme Being, as a personal creator and ruler of the

xi

world, Kapila never refers to Him in his Sūtras. As a careful reasoner, however, he does not go so far as to say that he can prove the non-existence of such a Being, but he is satisfied with stating, like Kant, that he cannot establish His existence by the ordinary channels of evidential knowledge. In neither of these statements can I discover, as others have done, any trace of intellectual cowardice, but simply a desire to abide within the strict limits of knowledge, such as is granted to human beings. He does not argue against the possibility even of the gods of the vulgar, such as Siva, Vishnu, and all the rest, He simply treats them as Ganyesvaras or Kāryesvaras, produced and temporal gods (Sūtras III, 57, comm.) he does not allow, even to the Supreme Īsvara, the Lord, the creator and the ruler of the world, as postulated by other systems of philosophy or religion, more than a phenomenal existence, though we should always remember that with him there is nothing phenomenal, nothing confined in space and time, that does not in the end rest on something real and eternal.

We must distinguish however. Kapila, though he boldly confessed himself an atheist, was by no means a nihilist or Nāstika. He recognised in every man a soul which he called Purusha, literally man, or spirit, or subject, because without such a power, without such endless Purushas, he held that Prakriti, or primordial matter with its infinite potentialities, would for ever have remained dead, motionless, and thoughtless. Only through the presence of this Purusha and through his temporary interest in Prakriti could her movements, her evolution, her changes and variety be accounted for, just as the movements of iron have to be accounted for by the presence of magnet. All this movement, however, is temporary only, and the highest

xii

object of Kapila’s philosophy is to make Purusha turn his eyes away from Prakriti, so as to stop her acting and to regain for himself his oneness, his aloneness, his independence, and his perfect bliss.

Whatever we may think of such views of the world as are put forward by the Sāmkhya, the Vedānta, and other systems of Indian philosophy, there is one thing which we cannot help admiring, and that is the straightforwardness and perfect freedom with which they are elaborated. However imperfect the style in which their theories have been clothed may appear from a literary point of view, it seems to me the very perfection for the treatment of philosophy. It never leaves us in any doubt as to the exact opinions held by each philosopher. We may miss the development and the dialectic eloquence with which Plato and Hegel propound their thoughts, but we can always appreciate the perfect freedom, freshness, and downrightness with which each searcher after truth follows his track without ever looking right or left.

It is in the nature of philosophy that every philosopher must be a heretic, in the etymological sense of the word, that is, a free chooser, even if like the Vedántist, he, for some reason or other, bows before his self-chosen Veda as the seat of a revealed authority.

It has sometimes been said that Hindu philosophy asserts, but does not prove, that it is positive throughout, but not argumentative. This may be true to a certain extent and particularly with regard to Vedānta-philosophy, but we must remember that almost the first question which everyone of the Hindu systems of philosophy tries to settle is, How do we know? In thus giving the Noȅtics the first place, the thinkers of the East seem to me again superior to most of the philosophers of the West. Generally speaking,

xiii

they admitted three legitimate channels by which knowledge can reach us, perception, inference, and authority, but authority freely chosen or freely rejected. In some systems that authority is revelation, Śruti, Sabda, or the Veda, in others it is the word of any recognised authority, Āptavacana. Thus it happens that the Sāmkhya philosophers, who profess themselves entirely dependent on reasoning (Manana), may nevertheless accept some of the utterances of the Veda could never make a false opinions of eminent men or Sishtas, though always with the proviso that even the Veda could never make a false opinion true. The same relative authority is granted to Smriti or tradition, but there with the proviso that it must not be in contradiction with Śruti or revelation.

Such an examination of the authorities of human knowledge (Pramāṇas) ought, of course, to form the introduction to every system of philosophy, and to have clearly seen this is, as it seems to me, a very high distinction of Indian philosophy. How much useless controversy would have been avoided, particularly among Jewish, Mohammedan, and Christian philosophers, if a proper place had been assigned in limine to the question of what constitutes our legitimate or our only possible channels of knowledge, whether perception, inference, revelation, or anything else!

Supported by these inquiries into the evidences of truth, Hindu philosophers have built up their various systems of philosophy, or their various conceptions of the world, telling us clearly what they take for granted, and then advancing step by step from the foundations to the highest pinnacles of their systems. The Vedántist, after giving us his reasons why revelation or the Veda stands higher with him than sensuous perception and inference, at least for the discovery of the highest truth (Paramārtha), actually puts

xiv

Śruti in the place of sensuous perception, and allows to perception and inference on more than an authority restricted to the phenomenal (Vyāvahārika) world. The conception of the world as deduced from the Veda, and chiefly from the Upanishads, is indeed astounding. It could hardly have been arrived at by a sudden intuition or inspiration, but presupposes a long preparation of metaphysical thought, undisturbed by any foreign influences. All that exists is taken as One, because if the existence of anything besides the absolute One or the Supreme Being were admitted, whatever the Second by the side of the One might be, it would constitute a limit to what was postulated as limitless, and would have made the concept of the One self-contradictory. But then came the question for Indian philosophers to solve, how it was possible, if there was but the One, that there should be multiplicity in the world, and that there should be constant change in our experience. They knew that the one absolute and undetermined essence, what they called Brahman, could have received no impulse to change, either from itself, for it was perfect, nor from others, for it was Second-less.

Then what is the philosopher to say to this manifold and ever-changing world? There is one thing only that he can say, namely, that it is not and cannot be real, but must be accepted as the result of nescience or Avidyā, not only of individual ignorance, but of ignorance as inseparable from human nature. That ignorance, though unreal in the highest sense, exist, but it can be destroyed by Vidyā, knowledge, i.e. the knowledge conveyed by the Vedānta, and as nothing that can at any time be annihilated has a right to be considered as real, it follows that this cosmic ignorance also must be looked upon as not real, but temporary only. It cannot be said to exist, nor can it be said

xv

not to exist, just as our own ordinary ignorance, though we suffer from it for a time, can never claim absolute reality and perpetuity. It is impossible to define Avidyā, as little as it is possible to define Brahman, with this difference, however, that the former can be annihilated, the latter never. The phenomenal world which, according to the Vedānta, is call forth, like the mirage in a desert, has its reality in Brahman alone. Only it must be remembered that what we perceive can never be the absolute Brahman, but a perverted picture only, just as the moon which we see manifold and tremulous in its ever changing reflections on the waving surface of the ocean, is not the real moon, though deriving its phenomenal character from the real moon which remains unaffected in its unapproachable remoteness. Whatever we may think of such a view of the cosmos, a cosmos which, it should be remembered, includes ourselves quite as much as what we call the objective world, it is clear that our name of nihilism would be by no means applicable to it.

The One Real Being is there, the Brahman, only it is not visible, nor perceptible in its true character by any of the senses; but without it, nothing that exists in our knowledge could exist, neither our Self nor what in our knowledge could exist, neither our Self nor what in our knowledge is our life.

This is one view of the world, the Vedānta view; another is that of the Sāmkhya, which looks upon our perceptions as perception of a substantial something, of Prakriti, the potentiality of all things, and treats the individual perceiver as eternally individual, admitting nothing besides these two powers, which by their union or identification cause what we call the world, and by their discrimination or separation produce final bliss or absoluteness.

These two, with some other less important views of the

xvi

world, as put forward by the other systems of Indian philosophy , constitute the real object of what was originally meant by philosophy, that is an explanation of the world. This determining idea has secured even to the guesses of Thales and Heraclitus their permanent place among the historical representatives of the development of philosophical thought by the side of Plato and Aristotle, of Des Cartes and Spinoza. It is in that Walhalla of real philosophers that I claim a place of honour for the representatives of the Vedānta and Sāmkhya. Of course, it is possible so to define the meaning of philosophy as to exclude men such as even Plato and Spinoza altogether, and to include on the contrary every botanist, entomologist, or bacteriologist. The name itself is of no consequence, but its definition is. And if hitherto no one would have called himself a philosopher who had not read and studied the works of Plato and Aristotle, of Descartes and Spinoza, Locke, Hume, and Kant in the original, I hope that the time will come when no one will claim that name who is not acquainted at least with the two prominent systems of ancient Indian philosophy, the Vedānta and the Sāmkhya. A President, however powerful, does not call himself His Majesty, why should an observer, a collector and analyser, however full of information, claim the name of philosopher?

As a rule, I believe that no one knows so well the defects of his book as the author himself, and I can truly say in my own case that few people can be so conscious of the defects of this History of Indian Philosophy as I myself. It cannot be called a history, because the chronological framework is, as yet, almost entirely absent. It professes to be no more than a description of some of the salient points of each of the six recognised systems of Indian

xvii

philosophy. It does not claim to be complete; on the contrary, if I can claim any thanks, it is for having endeavoured to omit whatever seemed to me less important and not calculated to appeal to Europe sympathies. If we want our friends to love our friends, we do not give a full account of every one of their good qualities, but we dwell on one or two of the strong points of their character. This is what I have tried to do for my old friends, Bādarāyaṇa, Kapila, and all the rest. Even thus it could not well be avoided that in giving an account of each of the six systems, there should be much repetition, for they all share so much in common, with but slight modifications; and the longer I have studied the various systems, the more have I become impressed with the truth of the view taken by Vigñāna-Bhikshu and others that there is behind the variety of the six systems a common fund of what may be called national or popular philosophy, a large Mānasa lake of philosophical thought and language, far away in the distant North, and in the distant Past, from which each thinker was allowed to draw for his own purposes. Thus, while I should not be surprised, if Sanskrit scholars were to blame me for having left out too much, students of philosophy may think that there is really too much, students of the same subject, discussed again and again in the six different schools. I have done my best, little as it may be, and my best reward will be if a new interest shall spring up for a long neglected mine of philosophical thought, and if my own book were soon to be superseded by a more complete and more comprehensive examination of Indian philosophy.

A friend of mine, a native of Indian, whom I consulted about the various degree of popularity enjoyed at the present day by different systems of philosophy in his own country, inform me that the only system that can now be

b

xviii

said to be living in India is the Vedānta with its branches, the Advaitis, the Madhvas, the Rāmānugas, and the Vallabhas. The Vedānta, being mixed with religion, he writes, has become a living faith, and numerous Pandits can be found to-day in all these sects who have learnt at least the principal works by heart and can expound them, such as the Upanishads, the Brahma-Sūtra, the great Commentaries of the Ākāryas and the Bhagavad-gītā. Some of the less important treatises also are studied, such as the Pañkadasī and Yoga-Vāsishtha (Yoga-Vaisheshika or Vaiśeṣika). The Pūrva-Mīmāmsā (Pūrva Mīmāṃsā) is still studied in Southern India, but not much in other parts, although expensive sacrifices are occasionally performed. The Agnishtoma was performed last year at Benares.

Of the other systems, the Nyāya only finds devotees, especially in Bengal, but the works studied are generally the later controversial treatises, not the earlier ones.

The Vaiseshika is neglected and so is the Yoga, except in its purely practical and most degenerate form.

It is feared, however, that even this small remnant of philosophical learning will vanish in one or two generations, as the youths of the present day, even if belonging to orthodox Brāhmanic families, do not take to these studies, as there is no encouragement.

But though we may regret that the ancient method of philosophical study is dying out in India, we should welcome all the more a new class of native students who, after studying the history of European philosophy, have devoted themselves to the honorable task of making their own national philosophy better known to the world at large. I hope that my book may prove useful to them by showing them in what direction they may best assist us in our attempts to secure a place to thinkers such as Kapila and Bādarāyana (Bādarāyaṇa) by the side of the leading philosophers of

xix

Greece, Rome, Germany, France, Italy, and England. In some cases the enthusiasm of native students may seem to have carried them too far, and a mixing up of philosophical with religious and theosophic propaganda, inevitable as it is said to be in India, is always dangerous. But such journals as the Pandit, the Brahmavādin (Brahmavādin or Brahmavidyā), the Light of Truth, and lately the Journal of the Buddhist text Society, have been doing most valuable service. What we want are texts and translations, and any information that can throw light on the chronology of Indian philosophy. Nor should their labour be restricted to Sanskrit texts. In the South of India there exists a philosophical literature which, though it may show clear traces of Sanskrit influence, contains also original indigenous elements of great beauty and of great importance for historical purposes. Unfortunately few scholars only have taken up, as yet, the study of the Dravidian languages and literature, but young students who complain that there is nothing left to do in Sanskrit literature, would, I believe, find their labours amply rewarded in that field. How much may be done in another direction by students of Tibetan literature in furthering a study of Indian philosophy has lately been proved by the publications of Sarat Chandra Das, C.I.E., and Satīs Chandra Acharya (Sanskrit: ācārya) Vidyābhūshana (Vidyābhūshaṇa), M.A., and their friends.

In conclusion I have to thank Mr. A. E. Gough, the translator of the Vaiseshika-Sūtras, and the author of the ‘Philosophy of the Upanishads,’ for his extreme kindness in reading a revise of my proof-sheets. A man of seventy-six has neither the eyes nor the memory which he had at twenty-six, and he may be allowed to appeal to younger men for such help as he himself in his younger days has often and gladly lent to his Gurus and fellow-labourers.

F. M. M.

OXFORD, May 1, 1899.

b 2

PREFACE TO SECOND EDITION.

THOUGH I am aware that the Six Systems of Indian Philosophy, the last large work written by my husband, and published only two months before the beginning of his fatal illness, shows some signs of weariness, and that the materials are perhaps less clearly gathered up and set before the reader than in his other works, I have had so many letters from friends in India as well as in England, expressing a desire for a second and cheaper edition, that I could not hesitate to comply with Messrs. Longmans’ wish to add the ‘Six Systems’ to the Collected Works. A friend on whose judgement I have complete reliance writes: ‘There is nothing like it in English for comprehensiveness of view, and it will long remain the most valuable introduction to the study of Indian philosophy in our language. It is an astonishing book for one who had passed threescore years and ten.’

GEORGINA MAX MÜLLER.

August, 1903.

Sources, Vocabularies, & Narratives:

01. adapted from. MAX MÜLLER, The Six Systems of Indian Philosophy, Longmans, Green and Co. 39 Paternoster Row, London Fourth Avenue & Street, New York, Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras 1919.