Title Thumbnail & Hero Image: ‘Paithan’ style scroll illustrating a narrative from the Mahabharata, depicting Sarasvati; Deccan, 19th-20th century. British Museum, Source: https://hinduaesthetic.medium.com, Access date: April 16, 2023.

Indian Philosophy Volume 1.005

- The Vedic Period: The Hymns of the Ṛg-Veda (Continue 2)

First revision: Apr.15, 2023

Last change: Jun.17, 2025

Searched, Gathered, Rearranged, Translated, and Compiled by Apirak Kanchanakongkha.

VI

MONOTHEISTIC TENDENCIES

As we shall see in our discussion of the Atharva-Veda, mythical conceptions from beyond the limits of the Aryan world belonging to a different order of thought entered into the Vedic pantheon. All this crowing of gods and goddesses proved a weariness to the intellect. So, a tendency showed itself very early to identify one god with another or throw all the gods together.

90

The attempts at classification reduced the gods to the three spheres of the earth, the air, and the sky. Sometimes these gods are said to be 333 or other combinations of three in number.1 The gods are also invoked in pairs when they fulfill identical functions. They are sometimes thrown together in one large Viśve devāḥ, or pantheon concept. This tendency at systematization had its natural end in monotheism, which is more straightforward and goddesses thwarting each other.

Monotheism is inevitable with any true conception of God. The Supreme can only be one. We cannot have two supreme and unlimited beings. Everywhere the question was asked whether a god was himself the creation of another. A created god is no God at all. With the growing insight into the world's workings and the godhead's nature, the many gods tended to melt into one. The perception of unity realized in the idea of Ṛta worked in support of monotheism. If the varied phenomena of nature demand many gods, should not the harmony of nature require a single god who embraces all things that are? Trust in natural law means faith in one God. The advance of this conception implies the paralysis of superstition. An orderly system of nature has no room for miraculous interferences in which superstition and confused thought alone to find the signs of polytheism. In the worship of Varuṇa, we have the nearest approach to monotheism. Attributes of moral and spiritual, such as justice, beneficence, righteousness, and even pity were ascribed to him. There has been a growing emphasis on the higher and more idealistic side to the suppression or comparative neglect of the gross or material side. Varuṇa is the god to whom man and nature, this world, and the other all belong. He cares not only for external conduct but also for the inner purity of life. The implicit demand of the religious consciousness for one supreme God manifested itself in what is characterized as the henotheism of the Vedas. It is according to Max Müller, who coined the term,

---------------

1. See R.V., iii. 9. 9.

91

the worshipping of each divinity in turn, as if were the greatest and even the only god. But the whole position is a logical contradiction, where the heart showed the right path of progress and belief contradicted it. We cannot have a plurality of gods, for religious consciousness is against it. Henotheism is an unconscious grouping towards monotheism. The weak mind of man is yet seeking for its object. The Vedic Aryan felt keenly the mystery of the ultimate and the inadequacy of the prevailing conceptions. The gods worshipped as supreme stand side by side, though for the moment only one holds the highest position. The one god is not the denial of the other gods. Even minor gods sometimes assume the highest rank. It all depends upon the devotion of the poet and the special object he has in view. “Varuṇa is the heaven, Varuṇa the earth, Varuṇa the air, Varuṇa is the universe and all besides.” Sometimes Agni is all gods. For the moment each god seems to become a composite photography of all others. Self-surrender of man to God, the central fact of religious experience, is possible only with one God. Thus, henotheism seems to be the result of the logic of religion. It is not, as Bloomfield suggests, “polytheism grown cold in service, and unnice in its distinctions, leading to an opportunist monotheism, in which every god takes hold of the sceptre and none keeps it.”1

When each god is looked upon as the creator and granted the attributes of Viśvakarman, maker of the world, and Prajāpati, lord of creatures, it is easy to drop the personal peculiarities and make a god of the common functions, especially when several gods are only cloudy and confused concepts and not real persons.

The gradual idealization of the conception of God as revealed in the cult of Varuṇa, the logic of religion which tended to make the gods flow into one another, the henotheism which had its face set in the direction of monotheism, the conception of Ṛta or the unity of nature, and the systematizing impulse of the human mind – all helped towards the displacement of a polytheistic anthropomorphism by a spiritual monotheism.

---------------

1. The Religion of the Veda, p. 199.

92

The Vedic seers at this period were interested in discovering a single creative cause of the universe, itself uncreated and imperishable. The only logical way of establishing such a monotheism was by subordinating the gods under one higher being, or controlling spirit, which could regulate the workings of the lower gods. This process satisfied the craving for one god and yet allowed them to keep up the continuity with the past. Indian thought, however daring and sincere, was never hard and rude. It did not usually care to become unpopular, and so generally made compromises; but pitiless logic, which is such a jealous master, had its vengeance, with the result that to-day Hinduism, on account of its accommodating spirit, has come to mean a heterogeneous mass of philosophies, religions, mythologies, and magics. The many gods were considered the different embodiments of the universal spirit. They were ruling in their respective spheres under the suzerainty of the supreme. Their powers were delegated, and their lordship was only a viceroyalty but not a sovereignty. The capricious gods of a confused nature-worship became the cosmic energies whose actions were regulated in a unified system. Even Indra and Varuṇa become departmental deities. The highest position in the later part of the Ṛg-Veda is granted to Viśvakarman.1 He is the all-seeing god who has on every side eye, faces, arms, feet, produces heaven and earth through the exercise of his arms and wings, knows all the worlds, but is beyond the comprehension of mortals. Bṛhaspati also has his claims for the supreme rank.2 In many places it is Prajāpati, the lord of creatures.3 Hiraṇyagarbha, the golden god, occurs as the name of the Supreme, described as the one Lord of all that exist.4

Viśvakarman or Phra Witsawakam, Thai Khon Mask, Source: www.pinterest.com, Access date: May 07, 2023.

Viśvakarman or Phra Witsawakam, Thai Khon Mask, Source: www.pinterest.com, Access date: May 07, 2023.

VII

MONOTHEISM versus MONISM

That even in the days of the Vedic hymns, we have not merely wild imagination and fancy but also earnest thought,

---------------

1. See x. 81. 82.

2. See x. 72.

3. See x. 85. 43; x. 189. 4; x. 184. 4; Śatapatha Brāh., vi. 6. 8. 1-14; x. 1. 3. 1.

4. x. 121.

93

and inquiry comes out from the fact that we often find the questioning mood asserting itself. The necessity to postulate several gods is due to the impulse of the mind, which seeks to understand things instead of accepting facts as they are given to it. “Where is the sun by night?” “Where go the stars by day?” “Why does the sun not fall down?” “Of the two, night and day, which is the earlier, which the later?” “Whence comes the wind, and whither goes it?”1 Such are the questions and the feelings of awe and wonder which constitute the birthplace of all science and philosophy. We have also seen the instinctive grouping for knowledge revealing itself in all forms and fancies. Many gods were asserted. The human heart’s longing could not be satisfied with a pluralistic pantheon. The doubt arose as to which god was the real one. Kasmai devāya haviṣā vidhema, “to what god shall we offer our oblation?”2 The humble origin of the gods was quite patent. The new gods grew on Indian soil, and some were borrowed from the native races. A prayer to make us faithful3 is not possible in a time of unshaken faith. Scepticism was in the air. Indra’s existence and supremacy were questioned.4 The nāstika or the denying spirit was busy at work dismissing the whole as a tissue of falsehood. Hymns were addressed to unknown gods. We reach the “twilight of the gods,” in which they are slowly passing away. In the Upaniṣads the twilight changed into night and the very gods disappeared but for the dreamers of the past. Even the single great Being of the monotheistic period did not escape criticism. The mind of man is not satisfied with an anthropomorphic deity. If we say there is one great god under whom the others are, the question is not left unasked. “Who has seen the firstborn, when he that had no bones bore him that has bones? Where is the life, the blood, the self of the universe? Who went to ask of any who knew?”5 It is the fundamental problem of philosophy. What is the life or essence of the universe? Mere dogma will not do. We must feel or experience the spiritual reality.

---------------

1. R. V., i. 24. 185.

2. x. 121.

3. x. 151.

4. x. 86. 1; vii. 100-3; ii, 12. 5.

5. R.V., i. 4. 164.

94

The question therefore is, “Who has seen the firstborn?”1 The seeking minds did not so much care for personal comfort and happiness as for absolute truth. Whether you look upon God with the savage as an angry and offended man or with the civilised as a merciful compassionate being, the judge of all the earth, the author and controller of the world, it is a weak conception that cannot endure criticism. The anthropomorphic ideas must vanish. They give us substitutes for God, but not the true living God. We must believe in God, the centre of life, and not His shadow as reflected in men’s minds. God is the inexhaustible light surrounding us on all sides. Prāṇo Virāṭ (“Life is immense”). It includes thoughts no less than things. The same reveals itself under different aspects. It is one, uniform, eternal, necessary, infinite and all-powerful. From it all flows out. To it all returns. Whatever the emotional value of a personal God may be, truth sets up a different standard and requires a different object of worship. However cold and remote, awful and displeasing it may seem to be, it does not cease to be the truth. Monotheism, to which a large part of humanity even to-day clings, failed to satisfy the later Vedic thinkers.

They applied to the central principle the neuter term Sat, to show that it is above sex. They were convinced that there was something real of which Agni, Indra, Varuṇa, etc. were only the forms or names. That something was, not many, but one, impersonal, ruling “over all that is unmoving and that moves, that walks or flies, being differently born.”2 “The real is one, the learned call it by various names, Agni, Yama and Mātariśvan.”3

The starry heavens and the broad earth, the sea and the everlasting hills,

Were all the workings of one mind, the features

Of the same face, blossoms upon one tree;

Characters of the great apocalypse,

The types and symbols of eternity,

The first and the last and midst and without end.4

---------------

1. Ko dadarśa Prathamā jāyamānam?

2. iii. 54. 8.

3. Ekaṁ sad viprā bahudhā vadanti

Agniṁ yamam mātariśvānam āhuḥ (i. 164. 46).

4. Wordsworth, Prelude 6.

95

This one is the soul of the world, the reason immanent in the universe, the source of all nature, the eternal energy. It is neither the heaven nor the earth, neither sunshine nor storm, but another essence, perhaps the Ṛta substantiated, the Aditi spiritualised, the one breathing breathless.1 We cannot see it, we cannot adequately describe it. With a touching sincerity the poet concludes: “We never will behold him who gave birth to these things.” “As a fool, ignorant in my own mind, I ask for the hidden places of the gods – not having discovered I ask the sages who may have discovered, not knowing in order to know.”2 It is the supreme reality which lives in all things and moves them all, the real one that blushes in the rose, breaks into beauty in the clouds, shows its strength in the storms and sets the stars in the sky. Here then we have the intuition of the true God, who of all the gods is the only God, wonderful any day, but surpassingly wonderful because it was at such an early hour in the morning of mind’s history that the true vision was seen. In the presence of this one reality, the distinction between the Aryan and the Dravidian, the Jew and the heathen, the Hindu and the Muslim, the pagan and the Christian, all fade away. We have here a momentary vision of an ideal where of all earthly religions are but shadows pointing to the perfect day. The one is called by many names. “Priest and poets with words make into many the hidden reality which is but one.”3 Man is bound to form very imperfect ideas of this vast reality. The desires of his soul seem to be well satisfied with inadequate ideas, “the idols which we here adore.” No two idols can be exactly the same, since no two men have exactly the same ideas. It is stupidity to quarrel about the symbols by which we attempt to express the real. The ONE God is called differently according to the different spheres in which he works or the tastes of the seeking souls. This is not to be viewed as any narrow accommodation to popular religion. It is a revelation of a profound philosophic truth. To Israel the same revelation came: “The Lord, thy Lord, thy God, is One.”

---------------

1. x. 129. 2.

2. R.V., x. 121; x. 82. 7; i. 167. 5-6.

3. x. 114; see also the Yajur-Veda, xxx. 2. 4. See Yāska’s Nirukta vii. 5.

96

Plutarch says: “There is One Sun and One sky over all nations and one Deity under many names.”

O! God, most glorious, called by many a name,

Nature’s Great King, though endless years the same;

Omnipotence, who by thy just decree

Controllest all, hail, Zeus, for unto thee

Behoves thy creatures in all lands to call.1

Of this monistic theory of the Ṛg-Veda Deussen writes: “The Hindus arrive at this monism by a method essentially different from that of other countries. Monotheism was attained in Egypt by a mechanical identification of the various local gods, in Palestine by proscription of other gods and violent persecution of their worshippers for the benefit of their national god Jehovah. In India they reached monism, though not monotheism on a more philosophical path, seeing through the veil of the manifold the unity which underlies it.”2 Max Müller says: “Whatever is the age when the collection of our Ṛg-Veda Saṁhitā was finished, it was before that age that the conviction had been formed that there is but One, One Being, neither male nor female, a Being raised high above all the conditions and limitations of personality and of human nature, and nevertheless the Being that was really meant by all such name as Indra, Agni, Mātariśvan, nay, even by the name of Prajāpati, Lord of creatures. In fact, the Vedic poets had arrived at a conception of the godhead which was reached once more by some of the Christian philosophers at Alexandria, but which even at present is beyond the reach of many who call themselves Christians.”3.

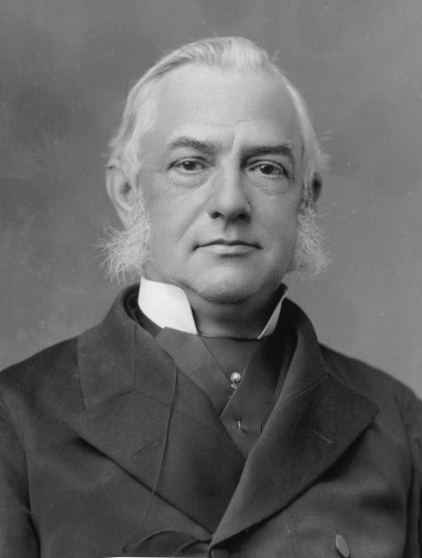

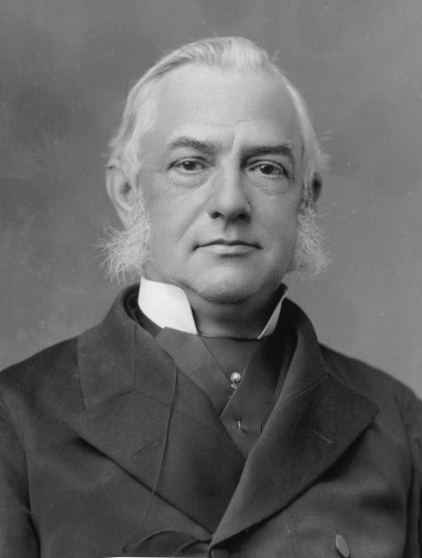

Friedrich Max Müller, source: en.wikipedia.org, access date: January 27, 2022.

Friedrich Max Müller, source: en.wikipedia.org, access date: January 27, 2022.

In some of the advanced hymns of the Ṛg-Veda the Supreme is indifferently called He or It. The apparent vacillation between monotheism and monism, a striking feature of Eastern as well of Western philosophy, revealed itself here for the first time in the history of thought. The same formless, impersonal, pure and passionless being of philosophy is worshipped by the warm full-blooded heart of the emotional man as a tender and benevolent deity.

---------------

1. The Hymn of Cleanthes.

2. Outlines of Indian Philosophy, p. 13.

3. S.S., pp. 51, 52.

97

Religious consciousness generally takes the form of a dialogue, a communion of two wills, finite and infinite. There is a tendency to make of God an infinite person over against the finite man. But this conception of God as one among many is not the highest truth of philosophy. Except for a few excessively logical people who wish to push their principles to their extreme conclusions, there cannot be religion without a personal God. Even the philosopher when asked to define the highest reality cannot but employ terms which reduce it to the lower level. Man knows that his limited powers cannot compass the transcendent vastness of the Universal Spirit. Yet he is obliged to describe the Eternal in his own small way. Bound down by his limitations he necessarily frames inadequate pictures of the vast, sublime, inscrutable source and energy of all things. He creates idols for his own satisfaction. Personality is a limitation, and yet only a personal God can be worshipped. Personality implies the distinction of self and not-self, and hence is inapplicable to the Being who includes and embraces all that is. The personal God is a symbol, though the highest symbol of the true living God. The formless is given a form, the impersonal is made personal; the omnipresent is fixed to a local habitation: the eternal is given a temporal setting. The moment we reduce the Absolute to an object of worship, it becomes something less than the Absolute. To have a practical relationship with finite will, God must be less than the Absolute, but if He is less than the Absolute, then He cannot be the object of worship in any effective religion. If God is perfect, religion is impossible; if God is imperfect, religion is ineffective. We cannot have with a finite limited God the joy of peace, the assurance of victory and the confidence in the ultimate destiny of the universe. True religion requires the Absolute. Hence to meet the demands of both popular religion and philosophy, the Absolute Spirit is indiscriminately called He or It. It is so in the Upaniṣads. It is so in the Bhagavadgītā and the Vedānta Sūtras. We need not put this down to a conscious compromise of theistic and monistic elements or any elusiveness of thought.

98

The monistic conception is also capable of developing the highest religious spirit. Only prayer to God is replaced by contemplation of the Supreme Spirit that rules the world, the love that thrills it in an unerring but yet lavish way. The sympathy between the mind of the part and that of the whole is productive of the highest religious emotion. Such an ideal love of God and meditation on the plenitude of beauty and goodness flood the mind with the cosmic emotion. It is true that such a religion seems to the man who has not reached it and felt its power too cold or too intellectual, yet no other religion can be philosophically justified.

All forms of religion which have appeared on earth assume the fundamental need of the human heart. Man longs for a power above him on which he could depend, One that is greater than himself whom he could worship. The gods of the several stages of the vedic religion are the reflections of the growing wants and needs, the mental groupings and the heart-searchings of man. Sometimes he would want gods who would hear his prayers and accept his sacrifices, and we have gods answering to this prescription. We have naturalistic gods, anthropomorphic gods, but none of them answered to the highest conception, however much one might try to justify them to the mind of man by saying that they were the varying expressions of the one Supreme. The scattered rays dispersed among the crowd of deities are collected together in the intolerable splendour of the One nameless God who alone could satisfy the restless craving of the human heart and the sceptic mind. The Vedic progress did not stop until it reached this ultimate reality. The growth of religious thought as embodied in the hymns may be brought out by the mention of the typical gods: (1) Dyáuṣ, indicative of the first state of nature worship; (2) Varuṇa, the highly moral god of a later day; (3) Indra, the selfish god of the age of conquest and domination; (4) Prajāpati, the god of the monotheists; and (5) Brahman, the perfection of all these four lower stages. This progression is as much chronological as logical.

Dyáuṣ or Dyáuṣpitṛ́ or Ākāśa - The Ṛg-Vedic sky deity, source: bloghemasic.blogspot.com, access date: August 29, 2021

99

Only in the Vedic hymns we find them all set down side by side without any conception of logical arrangement or chronological succession. Sometimes the same hymn has suggestions of them all. It only shows that when the text of the Ṛg-Veda came to be written all these stages of thought had already been passed, and people were clinging to some or all of them without any consciousness of their contradiction.

VIII

COSMOLOGY

The Vedic thinkers were not unmindful of the philosophical problems of the origin and nature of the world. In their search for the first ground of all changing things, they, like the ancient Greeks, looked upon water, air, etc., as the ultimate elements out of which the variety of the world is composed. Water is said to develop into the world through the force of time, saṁvatsara or year, desire or kāma, intelligence or puruṣa, warmth or tapas.1 Sometimes water itself is derive from night or chaos, tamas, or air.2 In x. 72 the world ground is said to be the asat, or the non-existent, with which is identified Aditi, the infinite. All that exist is diti, or bounded, while the a-diti, the infinite, is non-existent. From the infinite, cosmic force arises, though the latter is sometimes said to be the source of the infinite itself.3 These theories, however, soon related themselves to the non-physical, and physics by alliance with religion became metaphysics.

In the pluralistic stage the several gods, Varuṇa, Indra, Agni, Viśvakarman, were looked upon as the authors of the universe.4 The method of creation is differently conceived. Some gods are supposed to build the world as the carpenter builds a house. The question is raised as to how the tree or the wood out of which the work was built was obtained.5

---------------

1. x. 190.

2. x. 168

3. x. 72. 3.

4. vii. 86; iii. 32. 80; x. 81. 2 ; x. 72. 2; x. 121. 1.

5. x. 31. 7; cf. x. 81. 4.

100

At a later stage the answer is given that Brahman is the tree and the wood out of which heaven and earth are made.1 The conception of organic growth or development is also now and then suggested.2 Sometimes the gods are said to create the world by the power of sacrifice. This perhaps belongs to a later stage of Vedic thought.

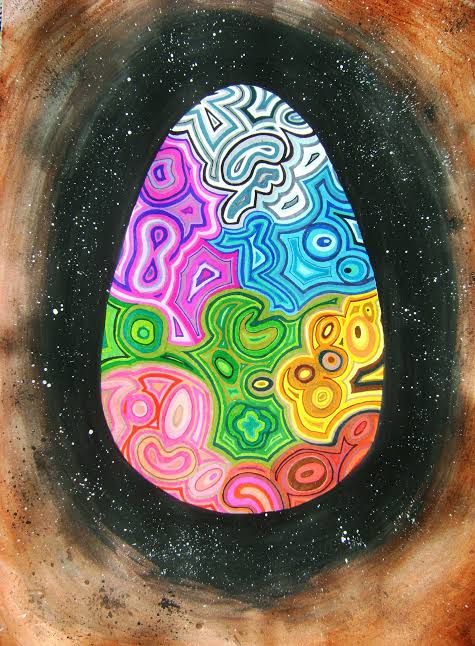

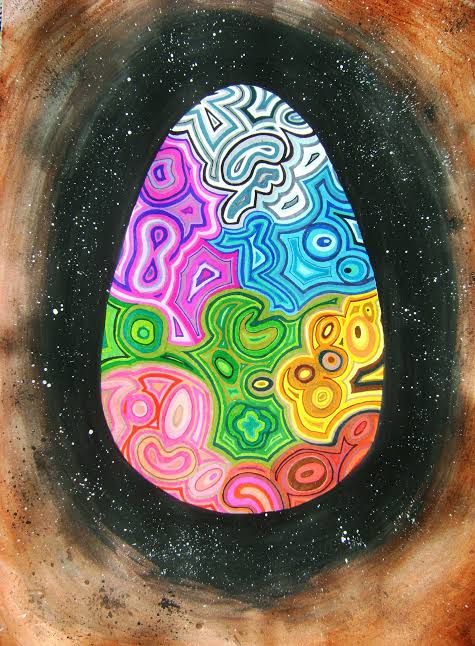

Hiraṇyagarbha, source: www.pinterest.com, access date: Apr.22, 2025.

Hiraṇyagarbha, source: www.pinterest.com, access date: Apr.22, 2025.1.

When we get to the monotheistic level the question arises as to whether God created the world out of His own nature without any pre-existent matter or through His power acting on eternity pre-existent matter. The former view takes us to the higher monistic conception, while the latter remains at the lower monotheistic level, and we have both views in the Vedic hymns. In x. 121 we have an account of the creation of the world by an Omnipotent God out of pre-existent matter. Hiraṇyagarbha arose in the beginning from the great water which pervaded the universe. He evolved the beautiful world from the shapeless chaos which was all that existed.3 But how did it happen, it is asked, that the chaos produced Hiraṇyagarbha? What is that unknown force or law of development which led to his rise? Who is the author of the primeval waters? According to the Manu, Harivaṁśa and the Purāṇas , God was the author of chaos. He created it by His will, and deposited a seed in it which became the golden germ in which He Himself was born as the Brahmā or the Creator God. “I am Hiraṇyagarbha, the Supreme Spirit Himself become manifested in the form of Hiraṇyagarbha.”4 Thus the two eternally co-existent substances seem to be the evolution of the one ultimate substratum.

This is exactly the theory of a later hymn called the Nāsadīya Hymn, which is translated by Max Müller.

There was then neither what is nor what is not, there was no sky,

nor the heaven which is beyond. What covered?

Where was it, and in whose shelter?

Was the water the deep abyss (in which it lay)?

There was no death, hence was there nothing immortal. There was no light (distinction) between night and day.

That One breathed by itself without breath, other than it there has been nothing.

---------------

1. See Tait. Brāh.

2. x. 123. i.

3. Cf. Manu, i. 5. 8. ; Maitrī Up., 5. 2.

4. Manu, v. 9.

101

Darkness there was, in the beginning all this was a sea without light;

the germ that lay covered by the husk, that One was born by the power of heat (tapas).

Love overcome it in the beginning, which was the seed springing from mind,

poets having searched in their heart found by wisdom the bond of what is in what is not.

Their ray which was stretched across, was it below or was it above? There were seed-bearers,

there were powers, self-power below, and will above.

Who then knows, who has declared it here, from whence was born this creation?

The gods came later than this creation, who then knows whence it arose?

He from whom this creation arose, whether he made it or did not make it,

the highest seer in the highest heaven, he forsooth knows, or does even he not know?1

We find in this hymn a representation of the most advanced theory of creation. First of all there was no existent or non-existent. The existent in its manifested aspect was not then. We cannot on that account call it the non-existent, for it is positive being from which the whole existence arrives. The first line brings out the inadequacy of our categories. The absolute reality which is at the back of the whole world cannot be characterised by us as either existent or non-existent. The one breathed breathless by its own power.2 Other than that there was not anything beyond. First cause of all it is older than the whole world, with the sun, moon, sky and stars. It is beyond time, beyond space, beyond age, beyond death and beyond immortality. We cannot express what it is except that it is. Such is the primal unconditioned groundwork of all being. Within that Absolute Consciousness there is first the fact of affirmation or positing of the primal “I.” This corresponds to the logical law of identity, A is A, the validity of which presupposes the original self-positing. Immediately there must be also a non-ego as the correlate of the ego. The I confronts the not-I, which answers to “A is not B.” The “I” will be a bare affirmation, a mere abstraction, unless there is another of which it is conscious. If there is no other, there is no ego. The ego implies non-ego as its condition. This opposition of ego and non-ego is the primary antithesis, and the development of this implication from the Absolute is said to be by tapas.

---------------

1. See Tait. Brāh.

2. Cf. Aristotle’s unmoved mover.

102

Tapas is just the “rushing forth,” the spontaneous “out-growth,” the projection of being into existence, the energising impulse, the innate spiritual fervour of the Absolute. Through this tapas we get being and non-being, the I and the not-I, the active Puruṣa and the passive prakṛti, the formative principle and the chaotic matter. The rest of the evolution follows from the interaction of these two opposed principles. According to the hymn, desire constitutes the secret of the being of the world. Desire or kama is the sign of self-consciousness, the germ of the mind, manasoretaḥ. It is the ground of all advance, the spur of progress. The self-conscious ego has desires developed in it by the presence of the non-ego. Desire1 is more than thought. It denotes intellectual stir, the sense of deficiency as well as active effort. It is the bond binding the existent to the non-existent. The unborn, the one, the eternal breaks forth into a self-conscious Brahmā with matter, darkness, non-being, zero, chaos opposed to it. Desire is the essential feature of this self-conscious Puruṣa. The last phrase, “ko veda?” (“who knows?”) brings out the mystery of creation which has led later thinkers to call it māyā.

There are hymns which stop with the two principles of Puruṣa and prakṛti. In x. 82. 5-6, of the hymn to Viśvakarman, we find it said that the waters of the sea contained the first or primordial germ. This first germ is the world egg floating on the primeval waters of chaos, the principle of the universe of life. From it arise Viśvakarman, the firstborn of the universe, the creator of the Greeks, the “without-form and void” of Genesis, with the infinite will reposing on it.2

---------------

Eros (Ἔρως), the Greek god of love and sex, developed on June 10, 2025.

Eros (Ἔρως), the Greek god of love and sex, developed on June 10, 2025. 1.

1. Greek mythology, it is interesting to notice, connects Eros, the god of love, corresponding to Kāma, with the creation of the universe. Plato says in his Symposium: “Eros neither had any parents nor is he said by any unlearned men or by any poet to have had any…” According to Aristotle, God moves as the object of desire.

2. Cf. it with the account of the Genesis: “And darkness was on the face of the deep and the spirit of God was moving on the face of the waters” (Gen. i. 2); see also R. V., x. 121; x 72.

103

Desire, will, self-consciousness, mind, vāk, or the word, all these are the qualities of the infinite intelligence, the personal God brooding over the waters, the Nārāyaṇa resting on the eternal Ananta. It is the god of Genesis who says, “Let there be, and there was.” “He thought, I will create the worlds, then He created these various worlds, water, light, etc.” The Nāsadīya hymn, however, overcomes the dualistic metaphysics in a higher monism. It makes nature and spirit both aspects of the one Absolute. The Absolute itself is neither the self nor the other, is neither self-consciousness of the type of I, nor unconsciousness of the type of not-I. It is a higher than both these. It is a transcending consciousness. The opposition is developed within itself. According to his account the steps of creation, when translated into modern terms, are: (1) the Highest Absolute; (2) the bare self-consciousness, I am I; (3) the limit of self-consciousness in the form of another. This does not mean that there is a particular point at which the Absolute moves out. The stages are only logically but not chronologically successive. The ego implies the non-ego, and therefore cannot precede it. Nor can the non-ego precede the ego. Nor can the Absolute be ever without doing tapas. The timeless whole is ever breaking out in a series of becomings, and the process will go on till the self reaffirms itself absolutely in the varied content of experience which is never going to be. So the world is always restless. The hymn tells us the how of creation, not the whence. It is an explanation of the fact of creation.1

नासदीयसूक्त - nāsadīya sūkta, source: elinepa.org (Hellenic-Indian Society for Culture & Development), access date: Jun. 17, 2025.

1.

We see clearly that there is no basis for any conception of the unreality of the world in the hymns of the Ṛg-Veda. The world is not a purposeless phantasm, but is just the evolution of God. Wherever the word māyā occurs, it is used only to signify the might or the power: “Indra takes many shapes quickly by his māyā.”2

---------------

1. Cf. with this the conception of a Demiurge, as used by Plato in the Timæus. The conception of creative imagination, set forth by E. Douglas Fawcett in his two books, The World as Imagination and Divine Imagining, may also be compared.

2. vi. 47. 18.

104

Yet sometimes māyā and its derivatives, māyin, māyāvant, are employed to signify the will of the demons,1 and we also find the word used in the sense of illusion or show.2 The main tendency of the Ṛg-Veda is naïve realism. Later Indian thinkers distinguish five elements, ether or ākāśa, air, fire, water and earth. But the Ṛg-Veda postulates only one, water. It is the primeval matter from which others slowly develop.

It is obviously wrong to think that according to the hymn we discussed there was originally non-being from out of which being grew. The first condition is not absolute non-existence, for the hymn admits the reality of the one breathing breathless by itself. It is their way of describing the absolute reality, the logical ground of the whole universe. Being and non-being, which are correlative terms, cannot be applied to the One which is beyond all opposition. Non-being only means whatever now visibly exists had then on distinct existence. In x. 72. 1, it is said, “the existent sprang from the non-existent.” Even here it does not mean being comes from non-being but only that distinct being comes from non-distinct being. So we do not agree with the view that the hymn is “the starting-point of the natural philosophy which developed into the Sāṁkhya system.”3

The creation of the world is sometimes traced to an original material as it were; in the Puruṣa Sūkta4 we find that the gods are the agents of creation, while the material out of which the world is made is the body of the great Puruṣa. The act of creation is treated as a sacrifice in which Puruṣa is the victim. “Puruṣa is all this world, what has been and shall be.”5 Anthropomorphism when once it is afoot cannot be kept within bounds, and the imagination of the Indian brings out the greatness of his God by giving him huge dimensions.

---------------

1. v. 2. 9; vi. 61. 3; i. 32. 4; vii. 49. 4; vii. 98. 5.

2. x. 54. 2.

3. See Macdonell, Vedic Reader, p.207. There are Vedic thinkers who postulate being or non-being as the first principle (x. 129. 1; x. 72. 2) so far as the world of experience is concerned, and these perhaps gave rise to the later logical theories of satkāryavāda, the existence of the effect in the cause, and asat kāryavāda, the non-existence of the effect in the cause.

4. x. 90.

5. x. 90. 2.

105

The poetic mind conjures up a vast composition pointing out the oneness of the whole, world and God. This hymn is not, however, inconsistent with the theory of creation from the One Absolute described above. The whole world even according to it is due to the self-diremption of the Absolute into subject and object, Puruṣa and Prakṛti. Only the idea is rather crudely allegorised. The supreme reality becomes the active Puruṣa, for it is said: “From the Puruṣa Virāt was born, and from Virāt again Puruṣa.” Puruṣa is thus the begetter as well as the begotten. He is the Absolute as well as the self-conscious I.

References:

01. from. INDIAN PHILOSOPHY Volume 1, written and composed by Servepalli Radhakrishnan, Oxford University Press, ISBN 019 563819 0, 5th impression 1999, New Delhi, Bhārata.

02. from. www.wisdomlib.org.