6. viii. 41.

7. vii. 87. 2.

8. i. 24. 8; ii. 28. 4; vii. 87. 5.

9. i. 24. 10 ; i. 25. 6; i. 44. 14; ii. 28. 8; iii. 54. 18; viii. 25.2.

10. vii. 87. 7.

1.

2.

78

sions of guilt and repentance,1 which show that the Aryan poets had a sense of the burden of sin and prayer.

The theism of the Vaiṣṇavas and the Bhāgavatas, with its emphasis on bhakti, is to be traced to the Vedic worship of Varuṇa, with its consciousness of sin and trust in divine forgiveness. Professor Macdonell says that “Varuṇa’s character resembles that of the divine ruler in a monotheistic belief of an exalted type.”2

The law of which Varuṇa is the custodian is called the Ṛta. Ṛta literally means “the course of things.” It stands for law in general and the immanence of justice. This conception must have been originally suggested by the regularity of the movements of sun, moon and stars, the alternations of day and of night, and of the seasons.

---------------

1. The following hymn to Varuṇa translated by Muir into verse, vol. v. O.S.T., p. 64. Though from the Atharva-Veda (iv. 16. 1-5), brings out the high conception of God cherished by the Vedic Aryans:

“The mighty lord on high, our deeds, as if at hand espies:

The gods know all men do, though men would fain their deeds disguise.

Whoever stands, whoever moves, or steals from place to place,

Or hides him in his secret cell – the gods his movements trace.

Wherever two together plot, and deem they are alone,

King Varuṇa is there, a third , and all their scheme are known.

This earth is his, to him belong those vast and boundless skies ;

Both seas within him rest, and yet in that small pool he lies.

Whoever far beyond the sky should think his way to wing,

He could not there elude the grasp of Varuṇa the king.

His spies descending from the skies glide all this world around,

Their thousand eyes all-scanning sweep to earth’s remotest bound.

Whate’er exists in heaven and earth, whate’er beyond the skies,

Before the eyes of Varuṇa, the king, unfolded lies.

The ceaseless winkings all he counts of every mortal’s eyes:

He wields this universal frame, as gamester throws his dice.

Those knotted nooses which thou fling’st, O God, the bad to snare, --

All liars let them overtake, but all the truthful spare.”

Again : “How can I get near to Varuṇa? will he accept my offering without displeasure? When shall I, with a quiet mind see him propitiated?”

“I ask, O Varuṇa, wishing to know this my sin ; I go to ask the wise, the sages, all tell me the same: Varuṇa it is who is angry with thee.”

“Was it for an old sin, O Varuṇa, that thou unconquerable Lord, and I will quickly turn to thee with praise, freed from sin.”

“Absolve us from the sins of our fathers, and from those which we committed with our own bodies.”

“It is not our own doing, Varuṇa, it was a slip; an intoxicating draught, passion, dice, thoughtlessness.”

2. Vedic Mythology, p. 3.

1.

2.

79

Ṛta denotes the order of the world. Everything that is ordered in the universe has Ṛta for its principle. It corresponds to the universals of Plato.1 The world of experience is a shadow or reflection of the Ṛta, the permanent reality which remains unchanged in all the welter of mutation. The universal is prior to the particular, and so the Vedic seer thinks that Ṛta exists before the manifestation of all phenomena. The shifting series of the world are varying expressions of the constant Ṛta. So Ṛta is called the father of all. “The Maruts come from afar from the seat of the Ṛta.”2 Viṣṇu is the embryo of the Ṛta.3 Heaven and Earth are what they are by reason of the Ṛta.4 The tendency towards the mystic conception of an unchanging reality shows its first signs here. The real is the unchanging law. What is, is an unstable show, an imperfect copy. The real is one without parts and changes, while the many shift and pass. Soon this cosmic order becomes the settled will of a supreme god, the law of morality and righteousness as well. Even the gods cannot transgress it. We see in the conception of Ṛta a development from the physical to the divine. Ṛta originally meant the “established route of the world, of the sun, moon and stars, morning and evening, day and night.” Gradually it became the path of morality to be followed by man and the law of righteousness observed even by gods. “The dawn follows the path of Ṛta, the right path; as if she knew them before. She never oversteps the regions. The sun follows the path of Ṛta.”5 The whole universe is founded on Ṛta and moves in it.6 This conception of Ṛta reminds us of Wordsworth’s invocation to duty.

Thou dost preserve the stars from wrong;

And the most ancient heavens, through thee, are fresh and strong.

---------------

Maruts, source: gloriousinduism.com, access date: Sep.11, 2025.

Maruts, source: gloriousinduism.com, access date: Sep.11, 2025.1.

1. Hegel characterises the categories or universals of logic as “God before the creation of the world or any planet.” I owe this reference to Professor J. S. Makenzie. The Chinese sage Lao Tsū recognises a cosmic order or the Tao, which serves as the foundation for his ethics, philosophy and religion.

2. iv. 21. 3.

3. i. 156. 3.

4. x. 121. 1.

5. i. 24. 8, Heraclitus says “Helios (the sun) will not overstep the bounds.”

6. iv. 23. 9.

1.

2.

80

What law is in the physical world, that virtue is in the moral world. The Greek conception of the moral life as a harmony or an ordered whole is suggested here. Varuṇa, who was first the keeper of the physical order, becomes the custodian of moral order, Ṛtasya gopa and the punisher of sin. The prayer to the gods is in many cases for keeping us in the right path. “O Indra, lead us on the path of Ṛta, on the right path over all evils.”1

So soon as the conception of Ṛta was recognised there was a change in the nature of gods. The world is no more a chaos representing the blind fury of chance elements but is the working of a harmonious purpose. This faith gives us solace and security whenever unbelief tempts us happen, we feel that there is a law of righteousness in the moral world answering to the beautiful order of nature. As sure as the sun rises to-morrow virtue will triumph. Ṛta can be trusted.

Mitra is the companion of Varuṇa and is generally invoked along with him. He represents sometimes the sun and sometimes the lights. He is also an all-seeing, truth-loving god. Mitra and Varuṇa are joint-keepers of the Ṛta and forgivers of sin. Gradually, Mitra comes to be associated with the morning light and Varuṇa with the night-sky. Varuṇa and Mitra are called the Ādityas, or the sons of Aditi, along with Aryaman and Bhaga.

Sūrya is the sun. He has some ten hymns addressed to him. The worship of the sun is natural to the human mind. It is an essential part of the Greek religion. Plato idealised sun-worship in the Republic. To him the sun was the symbol of the Good. In Persia we have sun-worship. The sun, the author of all light and life in the world, has supernatural powers assigned to him. He is the life of “all that moveth and standeth.” He is all seeing, the spy of the world. He rouses men to perform their activities, dispels darkness and gives light. “Sūrya is rising, to pace both worlds, looking down on men, protector of all that travel or stay, beholding right and wrong among men.”2 Sūrya becomes the creator of the world and its governor.

---------------

1. x. 133. 6.

2. R. V., vii. 60.

1.

2.

81

Savitṛ, celebrated in eleven entire hymns, is also a solar deity. He is described as golden-eyed, golden-handed and golden-tongued. He is sometimes distinguished from the Sun,1 though often identified with him. Savitṛ represents not only the bright sun of the golden day, but also the invisible sun of night. He has a lofty moral side, being implored by the repentant sinner for the forgiveness of sin: “Whatever offence we may have committed against the heavenly host, through feebleness of understanding, or through weakness or through pride or through human nature, O Savitṛ, take from us this sin.”2 The Gāyatī hymn is addressed to Sūrya in the form of Savitṛ; “Let us meditate on that adorable splendour of Savitṛ; may he enlighten our minds.” The oft-quoted hymn from the Yajur-Veda, “ O God Savitṛ the creator of All, remove the obstructions and grant the blessings,” is addressed to Savitṛ.

Lord Viṣṇu or Nārāyaṇa

Lord Viṣṇu or Nārāyaṇa1.

Sūrya in the form of Viṣṇu supports all the worlds.3 Viṣṇu is the god of three strides. He covers the earth, heaven and the highest worlds visible to mortals. None can reach the limits of his greatness. “We can from the earth know two of thy spaces, thou alone, O Viṣṇu, knowest thine own highest abode.”4 Viṣṇu holds a subordinate position in the Ṛg-Veda, though he has a great future before him. The basis of Vaiṣṇavism is, however, found in the Ṛg-Veda, where Viṣṇu is described as bṛhatśarīrah, great in body, or having the world for his body, pratyety āhavam, he who comes in response to the invitation of the devotee.5 He is said to have traversed thrice the earth spaces for the sake of man in distress.6

Pūṣan is another solar god. He is evidently a friend of man, being a pastoral god and the guardian of cattle. He is the god of wayfarers and husbandmen.

Ruskin says: “There is no solemnity so deep to a rightly thinking creature as that of the dawn.” The boundless dawn from which flash forth every morning light and life becomes the goddess Uṣas, the Greek Eos, the brilliant maid of morning loved by the Aśvins, and the sun, but vanishing before the latter as he tries to embrace her with his golden rays.

---------------

1. R.V., vii. 63.

2. iv. 54. 3.

3. i. 21. 154.

4. i. 22. 18; vii. 59. 1-2.

5. i. 155. 6.

6. Mānave bādhitāya, (Disturbed by the mind) iv. 6.

.jpg)

Pics from left to right: Thai depiction of the Horse-faced Aśvins on a chariot, Unknow painter, filed on January 1, 1959, and Aditi praying to the god Brahma. circa 19th century, from Saraswati Mahal Library Collection, Tanjore, both files from en.wikipedia.org, access date: Mar.30, 2023.

Pics from left to right: Thai depiction of the Horse-faced Aśvins on a chariot, Unknow painter, filed on January 1, 1959, and Aditi praying to the god Brahma. circa 19th century, from Saraswati Mahal Library Collection, Tanjore, both files from en.wikipedia.org, access date: Mar.30, 2023.1.

2.

82

The Aśvins are invoked in about fifty hymns and in parts of many other.1 They are inseparable twins, the bright lords of brilliance and luster , strong, and agile, and fleet as eagles. They are the children of Heaven, and the Dawn is their sister. It is supposed that the phenomenon of twilight is their material basis. That is why we have two Aśvins corresponding to the dawn and the dusk. They gradually become the physicians of gods and men, wonderworkers, protectors of conjugal love and life and the delivers of the oppressed from all kinds of suffering.

We have already mentioned Aditi from whom the several gods called Ādityas are born. Aditi literally means “unbound or unlimited.” It seems to be a name for the invisible, the infinite which surrounds us on all sides, and also stands for the endless expanse beyond the earth, the clouds and the sky. It is the immense substratum of all that is here and also beyond. “Aditi is the sky, Aditi is the intermediate region, Aditi is father and mother and son, Aditi is all the gods and the five tribes, Aditi is whatever has been born, Aditi is whatever shall be born.”2 here we have the anticipation of a universal all-embracing, all-producing nature itself, the immense potentiality or the prakṛti of the Sāṁkhya philosophy. It corresponds to Anaximander’s Infinite.

An important phenomenon of nature raised to a deity is Fire. Agni3 is second in importance only to Indra, being addressed in at least 200 hymns. The idea of Agni arose from the scorching sun, which by its heat kindled inflammable stuff. It came from the clouds as lightning. It has also its origin in flintstone.4 It comes from fire sticks.5 Mātariśvan, like Prometheus, is supposed to have brought fire back from the sky and entrusted it to the keeping of the Bhṛgus.6 The physical aspects are evident in the descriptions of Agni as possessing a tawny beard,

---------------

1. Aśvins are literally horsemen.

2. R.V., i. 89.

3. Latin Ignis.

4. ii. 12. 3.

5. Sanskrit araṇis.

6. The name of a clan.

1.

2.

83

sharp jaws and burning teeth. Wood or ghee is his food. He shines like the sun dispelling the darkness of night. His path is black when he invades the forests and his voice is like the thunder of heaven. He is Dhūmaketu, having smoke for his banner. “O Agni, accept this log which I offer to thee, blaze up brightly and send up thy sacred smoke, touch the topmost heavens with thy mane and mix with the beams of the sun.”1 Fire is thus seen to dwell not only on earth in the hearth and the altar but also in the sky and the atmosphere, as the sun and the dawn and as lightning in the clouds. He soon becomes a supreme god, stretching out heaven and earth. As the concept grew more and more abstract it also became more and more sublime. He becomes the mediator between gods and men, the helper of all. “O Agni, bring hither Varuṇa to our offering. Bring Indra from the skies, the Maruts from the air.”2 “I hold Agni to be my father. I hold him to be my kinsman, my brother, and also my friend.”3

Soma, the god of inspiration, the giver of immortal life, is analogous to the Haoma of the Avesta and Dionysos of Greece, the god of the wine and the grape. All these are the cults of the intoxicants. Miserable man requires something or other to drown his sorrow in. When he takes hold of an intoxicating drink for the first time, a thrill of delight possesses him. He is mad, no doubt but he thinks it is a divine madness. What we call spiritual vision, sudden illumination, deeper insight, larger charity and wider understanding – all these are the accompaniments of an inspired state of the soul. No wonder the drink that elevates the spirit becomes divine. Whitney observes: “The simple-minded Aryan people, whose whole religion was a worship of the wonderful powers and phenomena of nature, had no sooner perceived that the liquid had power to elevate the spirits and produce a temporary frenzy under the influence of which the individual was prompted to and capable of deeds beyond his natural powers, than they found in it something divine; it was to their apprehension a god, endowing those into whom it entered with god-like powers:

---------------

1. R.V., ii. 6.

2. R.V., x. 70. 11.

3. R.V/, x. 7. 3.

1.

2.

84

the plant which afforded it became to them the king of plants, the process of preparing was a holy sacrifice; the instruments used therefore were sacred. The high antiquity of this cultus is attested by the references to it found occurring in the Persian Avesta; it seems, however, to have received a new impulse on Indian territory.”1 Soma is not completely personalized. The plant and the juice are so vividly present to the poet’s mind that he cannot easily deify them. The hymns addressed to Soma were intended to be sung while the juice was being pressed out of the plant. “O Soma poured out for Indra to drink flow on purely in a most sweet and exhilarating current.”2 In viii. 48. 3 the worshipper immortal, we have drunk the Soma, we have known the intoxication is not peculiar to the Vedic age. William James tells us that the drunken consciousness is a bit of the divine through physical intoxication. Soma gradually acquires medicinal powers, helping the blind to see and the lame to walk.3 The following beautiful hymn to Soma points out how important a place he occupies in the affections of the Vedic Aryans.

Where there is eternal light, in the world, where the sun is placed, in that immortal,

imperishable world, place me, O Soma.

Where the son of Vivasvat reigns as King, where the secret place of heaven is, where

these mighty waters are, make me immortal.

Where life is free, in the third heaven of heavens, where the worlds are radiant, there

make me immortal.

Where wishes and desires are, where the bowl of the bright Soma is, where there is food and rejoicing, there

make me immortal.

Where there is happiness and delight, where joy and pleasure reside, where the

desires of our desire are attained, there make me immortal.4

In the hymn to Soma just quoted there is a reference to the son of Vivasvat, who is the Yama of the Ṛg-Veda answering to the Yima,

---------------

1. J.A.O.S., iii. 292.

2. ix. i.

3. vii. 68. 2, and x. 25. 11.

4. S.B.E., Vedic Hymns, part i. See Gilbert Murray’s translation of the Baachæ of Euripides, p. 20.

Yama, Picture from Angkor Wat, Cambodia, South Corridor, East Wing - Heavens and Hells, taken on October 20, 2018.1.

2.

85

The son of Vivanhvant of the Avesta. There are three hymns addressed to Yama. He is the chief of the dead, not so much a god as a ruler of the dead. He was the first of mortals to die and find his way to the other world, the first to tread the path of the fathers.1 Later he acts as the host receiving newcomers. He is the king of that kingdom, for he has the most extended experience of it. He is sometimes invoked as the god of the setting sun.2 In the Brāhmaṇas Yama becomes the judge and chastiser of men. But in the Ṛg-Veda, he is yet only their king. Yama illustrates the truth of the remark which Lucian puts into the mouth of Heraclitus : “What are men? Mortal gods. What are gods? Immortal men.”

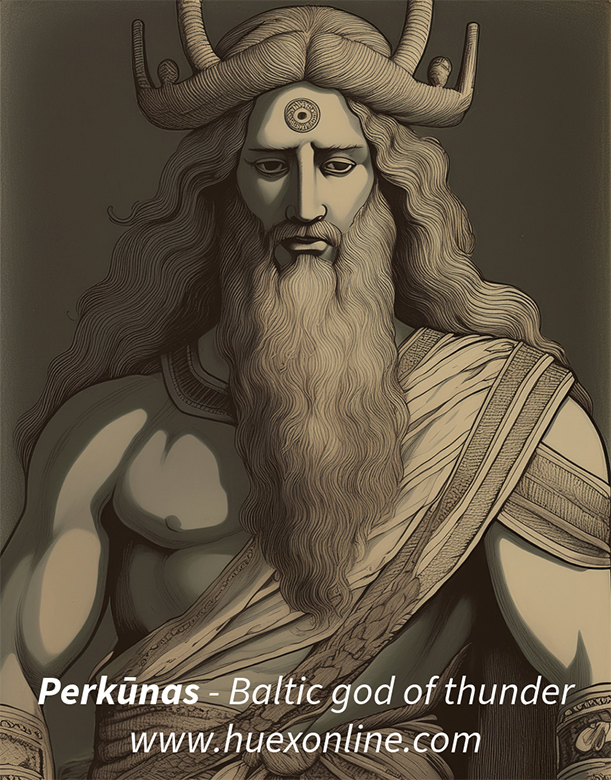

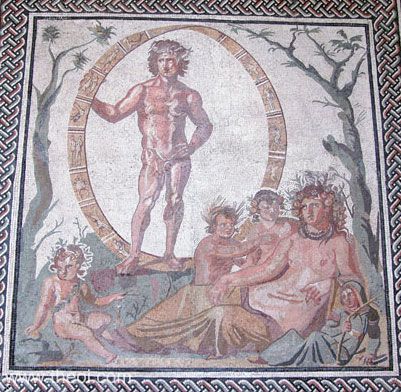

Parjanya was the Aryan sky god. He seems to have become Indra after the Aryans entered India, for Indra is unknown to the other members of the Aryan family. In the Vedas Parjanya is another name for the sky. “The Earth is the mother and I am the son of the Earth, Parjanya is the father. May he help us.”3 In the Atharva Veda Earth is called the wife of Parjanya.4 Parjanya is the god of cloud and rain.5 He rules as god over the whole world; all creatures rest in him; he is the life of all that moves and rest.6 There are also passages where the word Parjanya is used for cloud or rain.7 Max Müller is of opinion that Parjanya is identical with the Lithuanian god of thunder called Perkunas.8

Perkunas, developed on Nov.4, 2025.

Perkunas, developed on Nov.4, 2025.1.

Of all the phenomena of nature which arouse the feeling of awe and terror, nothing can challenge comparison with thunderstorms. “Yes, when I send thunder and lightning,’ says Indra, “then you believe in me.” Judging from the hymns addressed to him, Indra is the most popular god of the Vedas. When the Aryans entered India, they found that, as at present, their prosperity was a mere gamble in rain. The rain god naturally becomes the national god of the Indo-Aryans. Indra is the god of the atmospheric phenomena, of the blue sky. He is the Indian Zeus.

---------------

1. Pitṛyāna, x. 2. 7.

2. x. 14.

3. A.V., xii. 1. 12.

4. xii. I. 42.

5. R.V., v. 83.

6. R.V., vii. 101. 6.

7. See R.V., i. 164. 5; vii 61.

8. India; What can it teach us? Lect. VI.

1.

2.

86

His naturalistic origin is clean. He is born of waters and the cloud. He wields the thunder-bolt, and conquers darkness. He brings us light and life, gives us vigour and freshness. Heaven bows before him and the earth trembles at his approach. Gradually Indra’s connexion with the sky and the thunder-storms is forgotten. He becomes the divine spirit, the ruler of all the world and all the creatures, who sees and hears everything, and inspires men with their best thoughts and impulses.1 The god of the thunder-storm vanquishing the demons of drought, and darkness becomes the victorious god of battles of the Aryans in their struggles with the natives. The times were of great activity, and the people were engaged in an adventure of conquest and domination. He will have nothing to do with the native peoples of alien faiths. “The hero-god who as soon as born shielded the gods, before whose might the two worlds shook – that, ye people, is Indra; who made fast the earth and the heaving mountains, measured the space of air, upheld the heaven – that, ye people, is Indra; who slew the serpent and freed the seven streams, rescued the cows the pounder in battle – that ye people, is Indra; the dread god of whom ye doubting ask, where is he, and sneer, he is not, he who sweeps away the enemies’ possessions, have faith in him – that, ye people, is Indra; in whose might stand horses, cattle and armed hosts, to whom both lines of battle call – that, ye people, is Indra; without whose aid men never conquer, whose arrow little thought of slays the wicked – that, ye people, is Indra.”2 This champion-god acquires the highest divine attributes, rules over the sky, the earth, the waters and the mountains,3 and gradually displaces Varuṇa from his supreme position in the Vedic pantheon. Varuṇa, the majestic, the just and the serene, the constant in purpose, he is not fit for the struggling, conquering, active times on which the Aryans have entered. So we hear the echo of this great revolution in the Vedic world in some hymns.4

---------------

1. viii. 37. 3; viii. 78. 5.

2. R.V., ii. 12.

3. x. 89. 10.

4. (Varuṇa speaks): “I am the king; mine is the lordship. All the gods are subject to me, the universal life-giver, and follow Varuṇa’s ordinances. I rule in men’s highest sanctuary – I am king Varuṇa – I, O Indra, am Varuṇa, and mine are the two wide, deep, blessed worlds. A wise maker, I created all the beings; Heaven and earth are by me preserved. I made the flowing waters to swell. I established in their sacred seat the heavens. I, the holy Āditya, spread out the triparite universe” (heaven, earth and atmosphere).

(Indra speaks): “I am invoked by the steed-possessing men when pressed hard in battle; I am the mighty one who stirs up the fight and whirls up the dust, in my overwhelming strength. All that have I done, nor can the might of all the gods restrain me, the unconquered; when I am exhilarated by libations and prayers, then quake both boundless worlds.”

The Ṛṣi speaks: “That thou didst all these things, all beings know; and now thou hast proclaimed it to Varuṇa, O Ruler ! Thee Indra men praise as the slayer of Vṛtra; it was thou who didst let loose the imprisoned waters” (iv. 42).

“I now say farewell, to the father, the Asura; I go from him to whom no sacrifices are offered, to him to whom men sacrifice – in choosing Indra, I give up the father though I have lived with him many years in friendship. Agni, Varuṇa, and Soma must give way; the power goes to another. I see it come” (x.124).

Lord Kṛṣṇa, source: www.iskconmysore.org, access date: Apr.13, 2023.1.

2.

87

Indra had also to battle with other gods worshipped by the different tribes settled in India. There were worshippers of water,1 the Aśvattha tree.2 Many of the demons with whom Indra fought were the tribal gods such as Vṛtra, the serpent.3 Another foe of Indra, in the period of the Ṛg-Veda, was Kṛṣṇa, the deified hero of a tribe called the Kṛṣṇas. The verse reads: “The fleet Kṛṣṇa lived on the banks of Aṁśumatī (Jumna) river with ten thousand troops. Indra of his own wisdom became cognisant of this loud-yelling chief. He destroyed the marauding host for our benefit.”4 This is the interpretation suggested by Sāyaṇa, and the story has some interest in connection with the Kṛṣṇa cult. The later Purāṇas speak of the opposition between Indra and Kṛṣṇa. It may be that Kṛṣṇa is the god of the pastoral tribe which was conquered by Indra in the Ṛg-Veda period, though at the time of the Bhagavadgītā he recovered much lost ground and got reinforced by becoming identified with the Vāsudeva of the Bhāgavatas and the Viṣṇu of the Vaiṣṇavas. It is this miscellaneous origin and history that make him the author of the Bhagavadgītā, the person action of the Absolute,

---------------

1. x. 9. 1-3.

2. R.V., i. 135. 8.

3. R.V., vi. 33. 2; vi. 29. 6.

4. viii. 85. 13-15.

1.

2.

88

as well as the cowherd playing the flute on the banks of the Jumna.1

By the side of Indra are several minor deities representing other atmospheric phenomena, Vāta or Vāyu, the wind, the Maruts, the terrible storm-gods, and Rudra the howler. Of wind, a poet says: “Where was he born and whence did he spring, the life of the gods and the germ of the world? That god moves about, where he listeth, his voices are heard, but he is not to be seen.”2 Vāta is an Indo-Iranian god. The Maruts are the deifications of the great storms so common in India, “when the air is darken by dust and clouds, when in a moment the trees are stripped of their foliage, their branches shivered, their stems snapped, when the earth seems to reel and then mountains shake and the rivers are lashed into foam and fury.”3 Maruts are powerful and destructive usually, but sometimes they are also kind and beneficent. They lash the world from end to end, or clear the air and bring the rain.4 They are the comrades of Indra and sons of Dyaus. Indra is sometimes called the eldest of the Maruts. On Account of their fierce aspects they are considered to be the sons of Rudra the militant God.5 Rudra has a very subordinate position in the Ṛg-Veda, being celebrated only in three entire hymns. He holds a thunder-bolt in his arms and discharge lightning shafts from the skies. Later he becomes Śiva the benignant, with a whole tradition developed round him.6

We also come across certain goddesses similarity developed. Uṣas and aditi are goddess.

---------------

1. Later on, the Kṛṣṇa cult became superior to the lower forms of worship of snakes and serpents and the Vedic worship of Indra. Sister Nivedita writes: “Kṛṣṇa conquers the snake Kāliya and leaves his footprint on his head. Here is the same struggle that we can trace in the personality of Śiva as Nāgesvara between the new devotional faith and the old traditional worship of snakes and serpents. He persuades the shepherds to abandon the sacrifice to Indra. Here he directly overrides the older Vedic gods, who, as in some parts of the Himalayas to-day, seem to know nothing of the interposition of Brahmā” (Footfalls of Indian History, p.212).

2. x. 168. 34.

3. Max Müller: India; What can it teach us? P.180.

4. R.V., i. 37. 11; 64. 6; i.86. 10; ii. 34. 12.

5. i. 64. 2.

6. R.V., vii. 46. 3; i. 114. 10; i. 114. 1.

1.

2.

89

The river Sindhu is celebrated as a goddess in one hymn,1 and Sarasvatī, first the name of a river, gradually becomes the goddess of learning.2 Vāk is the goddess of speech. Araṇyānī is the goddess of the forest.3 The later Śākta systems utilize the goddesses of the Ṛg-Veda. The Vedic Aryan prayed to the Śākti or the energy of God, as he meditated on the adorable divine light that granted our prayers, Thou art the unperishing, the equal of Brahman.”4

When thought advanced from the material to the spiritual, from the physical to the personal, it was easy to conceive of abstract deities. Most of such deities occur in the last book of the Ṛg-Veda, thus indicating their relatively late origin. We have Manyu,5 Śraddhā,6 etc. Certain qualities associated with the true conception of god are deified. Tvaṣtṛ, sometimes identified with Savitṛ,7 is “the maker” or the constructor of the world. He forged India’s thunder-bolt, sharpened the axe of Brahmaṇaspati, made the cups out of which the gods drink Soma, and gave shape to all living things. Brahmaṇaspati is very late god, belonging to the period when sacrifices began to come into vogue. Originally the lord of prayer, he soon became the god of sacrifices. We see in him the transition between the spirit of the pure Vedic religion and the later Brāhmanism.8

---------------

1. x. 75. 2. 4, 6.

2. vi. 61.

3. x. 146.

4. Āyātu varadā devī, akṣaram brahmasammitam. Tait. Ār., x. 34. 52.

5. Wrath, x. 83. 4

6. Faith, x, 151.

7. iii. 55. 19.

8. Roth remarks: “All the gods whose names are compounded with pati (lord of) must be reckoned among the more recent. They were the products of reflection.” This is, however, incorrect as a general statement. Cf. Vāstoṣpati. I owe this information to Professor Keith.

1.

2.

3.

.jpg)