Title Thumbnail: Ṛg-Veda, Sanskrit, created: 1495-1735, held by British Library, source: bl.uk, access date: Apr.11, 2021.

Indian Philosophy Volume 1.003 - The Vedic Period: The Hymns of the Ṛg-Veda

First revision: Apr.11, 2021

Last change: Jul.17, 2025

Indian Philosophy Volume 1.003

Part I

THE VEDIC PERIOD

THE HYMNS OF THE ṚG-VEDA

1.

2.

63

CHAPTER II

THE HYMNS OF THE ṚG-VEDA

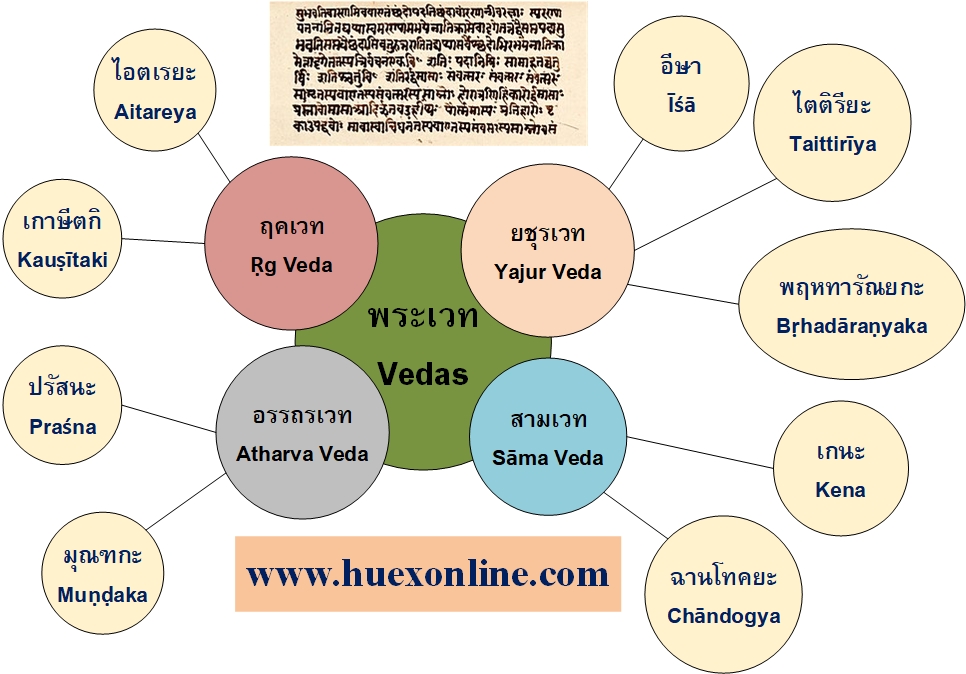

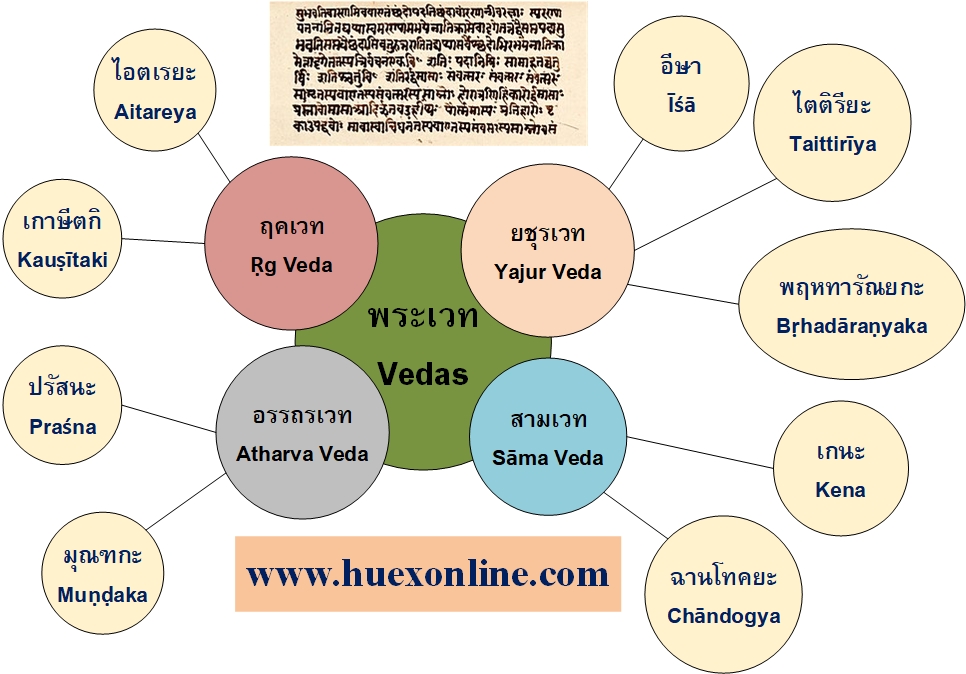

The four Vedas – The parts of the Veda, the Mantras, the Brāhmaṇas, the Upaniṣads – The importance of the study of the hymns – Date and authorship – Different views of the teaching of the Hymns – Their philosophical tendencies – Religion – “Deva” – Naturalism and anthropomorphism – Heaven and Earth - Varuṇa - Ṛta – Sūrya – Uṣas – Soma – Yama – Indra - Minor gods and goddesses – Classification of the Vedic deities – Monotheistic tendencies – The unity of nature – The unifying impulse of the logical mind – The implications of the religious consciousness – Henotheism – Viśvakarman, Bṛhaspati, Prajāpati and Hiraṇyagarbha – The rise of reflection and criticism – The philosophical inadequacy of monotheism – Monism – Philosophy and religion – The cosmological speculations of the Vedic hymns – The Nāsadīya Sūkta – The relation of the world to the Absolute – The Puruṣa Sūkta – Practical religion – Prayer – Sacrifice – The ethical rules – Karma – Asceticism – Caste – Future life – The two paths of the gods and the fathers – hell – rebirth – Conclusion.

1.

2.

I

THE VEDAS

THE Vedas are the earliest documents of the human mind that we possess. Wilson writes : “When the texts of the Ṛg and Yajur Vedas are completed, we shall be in the possession of materials sufficient for the safe appreciation of the results to be derived from them, and of the actual condition of the Hindus, both political and religious, at a date co-eval with that of the yet earliest known records of social organisation – long anterior to the dawn of Grecian civilisation – prior to the oldest vestiges of the Assyrian Empire yet discovered – contemporary probably with the oldest Hebrew writings, and posterior only to the Egyptian dynasties, of which, however, we yet know little except barren names ; the Vedas give us abundant information

1.

2.

64

respecting all that is most interesting in the contemplation of antiquity."1 There are four Vedas : Ṛg, Yajur, Sāma and Atharva. The first three agree not only in their name, form and language, but in their contents also. Of them all the Ṛg-Veda is the chief. The inspired songs which Aryans brought with them from their earlier home into India as their most precious possession were collected, it is generally held, in response to a prompting to treasure them up which arose when the Aryans met with large numbers of the worshippers of other gods in their new country. The Ṛg-Veda is that collection. The Sāma-Veda is a purely liturgical collection. Much of it is found in the Ṛg-Veda, and even those hymns peculiar to it have no distinctive lessons of their own. They are all arranged for being sung at sacrifices. The Yajur-Veda, like the Sāma, also serves a liturgical purpose. This collection was made to meet the demands of ceremonial religion. Whitney writes : “In the early Vedic times the sacrifice was still, in the main, an unfettered act of devotion, not committed to the charge of a body of privileged priests, not regulated in its minor details, but left to the free impulses of him who offered it, accompanied with Ṛg and Sāma hymns and chants, the mouth of the offer might not be silent while his hands were presenting to the divinity the gift which his heart prompted. . . . As in process of time, however, the ritual assumed a more and more formal character, becoming finally a strictly and minutely regulated succession of single actions, not only were the verses fixed which were to be quoted during the ceremony, but there established themselves likewise a body of utterances, formulas of words, intended to accompany each individual action of the whole work to explain, excuse, bless, give it a symbolical significance or the like. . . . These sacrificial formulas received the name of Yajus, from the root Yaj, to sacrifice. . . . The Yajur-Veda is made up of these formulas, partly in prose and partly in verse, arranged in the order in which they were to be made use of at the sacrifice."2 The collections of the Sāma and the Yajur Vedas must have been

---------------

1. J. R. A. S., vol. 13, 1852, p. 206.

2. A. O. S. Proceedings, vol. iii. P. 304.

1.

2.

65

made in the interval between the Ṛg-Vedic collection and the Brāhmanical period, when the ritualistic religion was well established. The Artharva-Veda for a long time was without the prestige of a Veda, though for our purposes it is next in importance only to the Ṛg-Veda, for like it, it is an historical collection of independent contents. A different spirit pervades this Veda, which is the production of a later era of thought. It shows the result of the compromising spirit adopted by the Vedic Aryans in view of the new gods and goblins worshipped by the original peoples of the country whom they were slowly subduing.

1.

1.

---------------

1. R.V., i. 164. 6.; x. 129. 4.

1.

2.

66

correspond in a very close way to the three great divisions in the Hegelian conception of the development of religion. Though at a later stage the three have existed side by side, there is no doubt that they were originally developed in successive periods. The Upaniṣads, while in one sense a continuation of the Vedic worship, are in another a protest against the religion of the Brāhmaṇas.

1.

2.

II

IMPORTANCE OF THE STUDY OF THE VEDIC HYMNS

A study of the hymns of the Ṛg-Veda is indispensable for any adequate account of Indian thought. Whatever we may think them, half-formed myths or crude allegories, obscure groupings or immature compositions, still they are the source of the later practices and philosophies of the Indo-Aryans, and a study of them is necessary for a proper understanding of subsequent thought. We find a freshness and simplicity and an inexplicable charm as of the breath of the spring or the flower of the morning about these first efforts of the human mind to comprehend and express the mystery of the world.

The text of the Veda which we possess has come to us from that period of intellectual activity when the Aryans found their way into India from their original home. They brought with them certain notions and beliefs which were developed and continued on the Indian soil. A long interval must have elapsed between the composition and the compilation of these hymns. Max Müller divides the Saṁhitā periods.1 In the former the hymns were composed. It was the creative epoch characterised by real poetry, when men’s emotions poured themselves out in songs; we have then on traces of sacrifices. Prayer was the only offering made to the gods. The second is the period of collection or systematic grouping. It was then

---------------

1. Attempts are sometimes made to assign the hymns to five different periods marked by differences of religious belief and social custom. See Arnold: Vedic Metre.

1.

2.

67

that the hymns were arranged in practically the same form in which we have them at present. In this period sacrificial ideas slowly developed. When exactly the hymns were composed and collected is a matter of conjecture. We are sure that they were current some fifteen centuries before Christ. Buddhism, which began to spread in India about 500 B.C., presupposes not only the existence of the Vedic hymns but the whole Vedic literature, including the Brāhmaṇas and the Upaniṣads. For the sacrificial system of the Brāhmaṇas to become well established, for the philosophy of the Upaniṣads to be fully developed, it would require a long period.1 The development of thought apparent in this vast literature requires at least a millennium. This is not too long a period if we remember the variety and growth which the literature displays. Some Indian scholars assign the Vedic hymns to 3000 B.C., others to 6000 B.C. The late Mr. Tilak dates the hymns about 4500 B.C., the Brāhmaṇas 2500 B.C., the early Upaniṣads 1600 B.C. Jacobi puts the hymns at 4500 B.C. We assign them to the fifteenth century B.C. and trust that our date will not be challenged as being too early.

The Ṛg-Veda Saṁhitā or collection consists of 1,017 hymns or sūktas, covering a total of about 10,600 stanzas. It is divided into eight aṣṭakas.2 each having eight adhyāyas, or chapters, which are further subdivided into vargas or groups. It is sometimes divided into ten maṇḍalas or circles. The latter is the more popular division. The maṇḍala contains 191 hymns, and is ascribed roughly to fifteen different authors or Ṛṣis (seers or sages) such as Gautama, Kaṇva, etc. In the arrangement of the hymns there is a principle involved. Those addressed to Agni come first, those to Indra second, and then the rest. Each of the next six maṇḍalas is ascribed to a single family of poets, and has the same arrangement. In the eighth we have no definite order. It is ascribed like the first to a number of different authors. Maṇḍala nine consists of hymns addressed to Soma. Many of the hymns of the eighth

--------------

1. From them many of the technical terms of later philosophies, such as Brahman, Ātman, Yoga, Mīmāṁsā, are derived.

2. An eighth portion is an aṣṭaka.

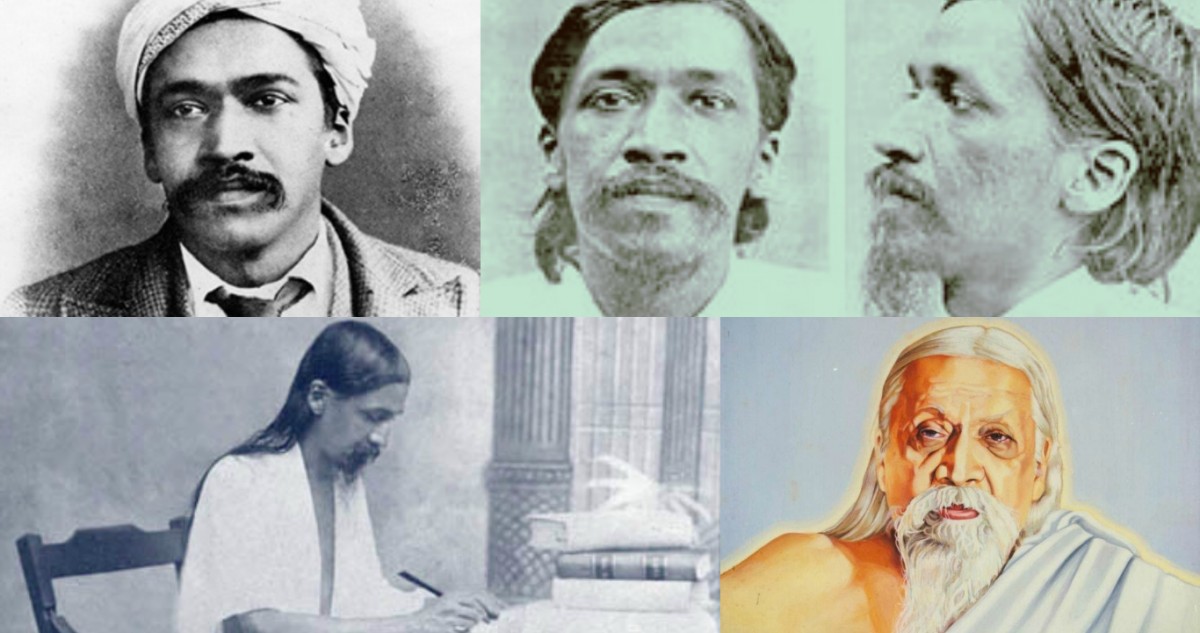

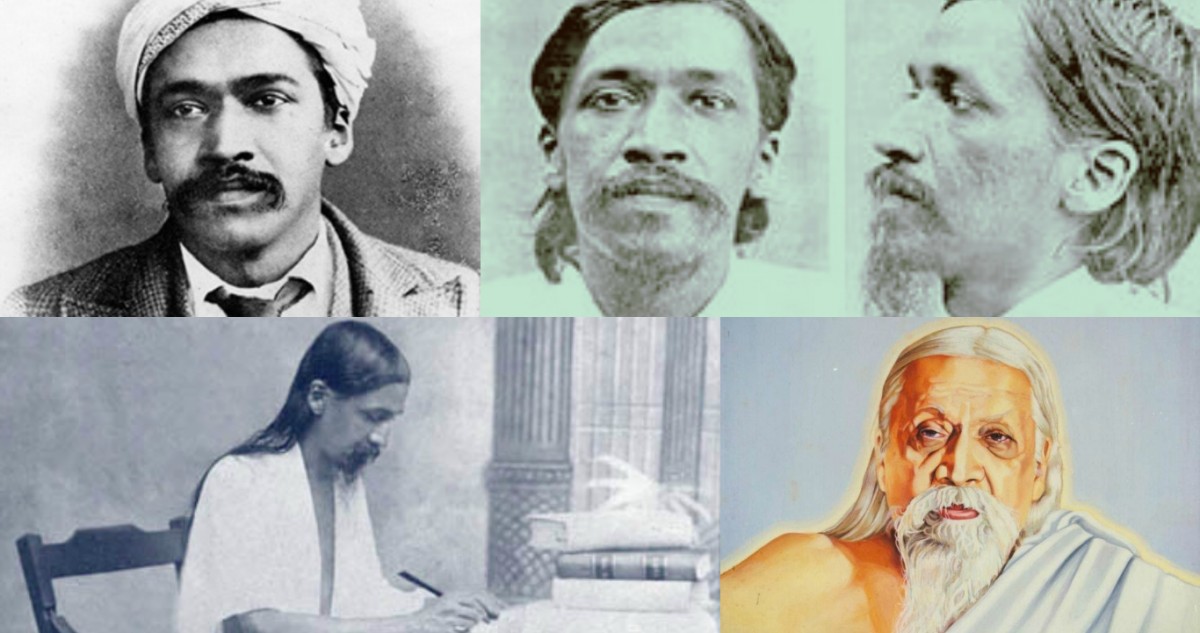

Bal Gangadhar Tilak, source: www.culturalindia.net, access date: January 5, 2023.

1.

Hermann Georg Jacobi, source: ru.wikipedia.org, access date: March 6, 2021.

1.

2.

68

and ninth Maṇḍalas are found in the Sāma-Veda also. Maṇḍala ten seems to be a later appendage. At any rate, it contains views current at the last period of the development of the Vedic hymns. Here the native hue of the earlier devotional poetry is sicklied over with the pale cast of philosophic thought. Speculative hymns about the origin of creation, etc., are to be met with. Together with these abstract theorisings are also found in it the superstitious charms and exercising belonging to the Atharva-Veda period. While the speculative parts indicate the maturing of the mind which first revealed itself in the lyrical hymns, this feature shows that by that time the Vedic Aryans must have grown familiar with the doctrines and practices of the native Indians, and both these are clear indications of the late origin of the tenth book.

1.

2.

III

THE TEACHING OF THE VEDAS

Different views of the spirit of the Vedic hymns are held by competent scholars who have made these ancient scriptures their life study. Pfleiderer speaks of the “primæval child-like naïve prayer of Ṛg-Veda.” Pictet maintains that the Aryans of the Ṛg-Veda possessed a monotheism, however vague and primitive it might be. Roth and Dayānanda Sarasvatī, the founder of the Arya Samaj, agree with this view. Ram Mohan Roy01 considers the Vedic gods to be “the allegorical representations of the attributes of the supreme Deity.” According to others, Bloomfield among them, the hymns of the Ṛg-Veda are sacrificial compositions of a primitive race which attached great importance to ceremonial rites. Bergaigne holds that they were all allegorical. Sāyaṇa, the famous Indian commentator, adopts the naturalistic interpretation of the gods of the hymns, which is supported by modern European scholarship. Sāyaṇa sometimes interprets the hymns in the spirit of the later Brāhmanic religion. These varying opinions need not be looked upon as antagonistic to one another, for they only point to the heterogeneous

Notes and narratives

01 Ram Mohun Roy, (born May 22, 1772, Radhanagar, Bengal, India—died Sept. 27, 1833, Bristol, Gloucestershire, Eng.), Indian religious, social, and political reformer. Born to a prosperous Brahman family, he traveled widely in his youth, exposing himself to various cultures and developing unorthodox views of Hinduism. In 1803 he composed a tract denouncing India’s religious divisions and superstitions and advocating a monotheistic Hinduism that would worship one supreme God. He provided modern translations of the Vedas and Upanishads to provide a philosophical basis for his beliefs, advocated freedom of speech and of religion, and denounced the caste system and suttee. In 1826 he founded the Vedanta College, and in 1828 he formed the Brahmo Samaj. Source: britannica.com, access date: April 14, 2022.

1.

2.

69

Nature of the Ṛg-Veda collection. It is a work representing the thought of successive generations of thinkers, and so contains within it different strata of thought. In the main, we may say that the Ṛg-Veda represents the religion of an unsophisticated age. The great mass of the hymns are simple and naïve, expressing the religious consciousness of a mind yet free from the later sophistication. There are also hymns which belong to the later formal and conventional age of the Brāhmaṇas. There are some, especially in the last book, which embody the mature results of conscious reflection on the meaning of the world and man’s place in it. Monotheism characterises some of the hymns of the Ṛg-Veda. There is no doubt that sometimes the several gods were looked upon as the different names and expressions of the Universal Being.1 But this monotheism is not as yet the trenchant clear-cut monotheism of the modern world.

Mr.Aurobindo Ghose (Sri Aurobindo) (August 15, 1872, Kolkata, India – December 5, 1950, Puducherry, India), source: pragyata.com, access date: Aug.29, 2021.

1.

Mr. Aurobindo Ghosh, the great Indian scholar-mystic, is of opinion that the Vedas are replete with suggestions of secret doctrines and mystic philosophies. He looks upon the gods of the Hymns as symbols of the psychological functions. Sūrya signifies intelligence, Agni will, and Soma feeling. The Veda to him is a mystery religion corresponding to the Orphic and Eleusinian creeds of ancient Greece. “The hypothesis I propose is that the Ṛg-Veda is itself the one considerable document that remains to us from the early period of human thought of which the historical Eleusinian and Orphic mysteries were the failing remnants, when the spiritual and psychological knowledge of the race was concealed for reasons now difficult to determine, in a veil of concrete and material figures and symbols which protected the sense from the profane and revealed it to the initiated. One of the leading principles of the mystics was the sacredness and secrecy of self-knowledge and the true knowledge of the gods. This wisdom was, they thought, unfit for, perhaps even dangerous, to the ordinary human mind, or in any case liable to perversion and misuse and loss of virtue if revealed to vulgar and unpurified spirits. Hence they favoured the existence of

---------------

1 See R.V., i. 164-46 and 170-71.

1.

2.

70

an outer worship effective but imperfect for the profane, and an inner discipline for the initiate, and clothed their language in words and images which had equally a spiritual sense for the elect and a concrete sense for the mass of ordinary worshippers. The Vedic hymns were conceived and constructed on these principles.”1 When we find that this view is opposed not only to the modern views of European scholars but also to the traditional interpretations of Sāyaṇa and the system of Pūrva-Mīmāṁsā, the authority on Vedic interpretation, we must hesitate to follow the lead of Mr. Aurobindo Ghosh, however ingenious his point of view may be. It is not likely that the whole progress of Indian thought has been a steady falling away from the highest spiritual truths of the Vedic hymns. It is more in accordance with what is known of the general nature of human development, and easier to concede that the later religions and philosophies arose out of the crude suggestions and elementary moral ideas and spiritual aspirations of the early mind, than that they were a degradation of an original perfection.

In interpreting the spirit of the Vedic hymns we propose to adopt the view of them accepted by the Brāhmaṇas and the Upaniṣads, which came immediately after. These later works are a continuation and a development of the views of the hymns. While we find the progress from the worship of outward nature powers to the spiritual religion of the Upaniṣads easily intelligible according to the law of normal religious growth-man everywhere on earth starts with the external and proceeds to the highest religion contained in the Vedas. This interpretation is in entire harmony with the modern historical method and the scientific theory of early human culture, and accords well with the classic Indian view as put forth by Sāyaṇa.

---------------

1 Arya, vol. i. p. 60.

71

IV

PHILOSOPHICAL TENDENCIES

In the Ṛg-Veda we have the impassioned utterances of primitive but poetic souls which seek some refuge from the obstinate questionings of sense and outward things. The hymns are philosophical to the extent that they attempt to explain the mysteries of the world not by means of any superhuman insight or extraordinary revelation, but by the light of unaided reason. The mind revealed in the Vedic hymns is not of any one type. There were poetic souls who simply contemplated the beauties of the sky and the wonders of the earth, and eased their musical souls of their burden by composing hymns. The Indo-Iranian gods of Dyaus, Varuṇa, Uṣas, Mitra, etc., were the productions of this poetic consciousness.

Dyaus Pita (or ākāśa, Akasha), source: bloghemasic.blogspot.com, access date: Aug.29, 2021.

1.

Others of a more active temperament tried to adjust the world to their own purposes. Knowledge of the world was useful to them as the guide of life. And in the period of conquest and battle, such useful utilitarian deities as Indra were conceived. The genuine philosophical impulse, the desire to know and understand the world for its own sake, showed itself only at the end of this period of storm and stress. It was then that men sat down to doubt the gods they ignorantly worshipped and reflected on the mysteries of life. It is at this period that questions were put to which the mind of man could not give adequate answers. The Vedic poet exclaims: “I do not know what kind of thing I am; mysterious, bound, my mind wanders.” Even though germs of true philosophy appear at a late stage, still the view of life reflected in the poetry and practice of the Vedic hymns is instructive. As legendary history precedes archæology, alchemy chemistry, and astrology astronomy, even so mythology and poetry precede philosophy and science. The impulse of philosophy finds its first expression in mythology and religion. In them we find the answers to the questions of ultimate existence, believed by the people in general. These happen to be products of imagination,

72

where mythical causes are assumed to account for the actual world. As reason slowly gains ascendancy over fancy, an attempt is made to distinguish the permanent stuff from out of which the actual things of the world are made. Cosmological speculations take the place of mythical assumptions. The permanent elements of the world are deified, and thus cosmology becomes confused with religion. In the early stages of reflection as we have them in the Ṛg-Veda, mythology, cosmology and religion are found intermixed. It will be of interest to describe briefly the views of the hymns under the four heads of theology, cosmology, ethics and eschatology.

1.

2.

3.