It is the ultimate presupposition of all philosophy that nothing real can be self-contradictory. In the history of thought it takes some time to realise the importance of this presupposition, and make a conscious application of it. In the Ṛgveda there is an unconscious acceptance of the validity of ordinary knowledge. When we reach the stage of the Upaniṣads, dialectical problems merge and the difficulties of knowledge are felt. In them we find an attempt made to mark the limits of knowledge and provide room for intuition, but all in a semi-philosophical way. When faith in the power of reason was shaken, scepticism supervened, and materialists and nihilists came upon the scene. Admitting the Upaniṣad position that the unseen reality cannot be comprehended by the logical intellect, Buddhism enforced the unsubstantiality of the world. To it, contradiction is of the nature of things, and the world of experience is nothing more than a tension of opposites. We cannot know if there is anything more than the actual, and this cannot be real since it is self-contradictory. Such a conclusion was the end of the Buddhistic development. We have in the theory of Nāgārjuna a philosophically sustained statement of the central position of the Upaniṣads. There is a real, though we cannot know it ; and what we know is not real, for every interpretation of the world as an intelligible system breaks down. All this prepared the way for a self-conscious criticism of reason. Thought itself is self-contradictory or inadequate. Differences arise when the question is put, why exactly is incapable of grasping reality. Is it because it deals with parts and not the whole, or is it because of its structural incapacity or innate self-contradictoriness ? As we have seen, there are those who hold to the rationality of the real with the reservation that reality is not mere reason. So thought is incapable of giving us the whole of reality. The “that” exceeds the “what” in Bradley’s words. Thought gives us knowledge of reality, but it is only knowledge, and not reality. There are others who feel that the real is self-consistent, and whatever is thought is self-contradictory. Thought works with the opposition of subject

43

and object, and the absolute real is something in which these antitheses are annulled. The most concrete thought, in so far as it tries to combine a many in one, is still abstract, because it is self-contradictory, and if we want to grasp the real, we have to give up thought. On the first hypothesis, what thought reveals is not opposed to reality, but is revelatory of a part of it. Partial views are contradictory only because they are partial. They are true so far as they go, but they are not the whole truth. The second hypothesis tells us that reality can be apprehended by a form of feeling or intuition.1 The first view also insists on a supplementing of thought by feeling, if reality is to be attained in its fullness. We seem to require another element in addition to thought, and this is suggested by the term “darśana,” which is used to describe a system of philosophy, doctrine or śāstra.

Francis Herbert Bradley, (Jan.30, 1846 – Sep.18, 1924) was an English philosopher. His most notable works include Appearance and Reality. Source: alchetron.com and en.wikipedia.org, access date: May 20, 2021.

1.

The term “darśana” comes from the word dṛś, to see. This seeing may be either perceptual observation or conceptual knowledge or intuitional experience. It may be inspection of facts, logical inquiry or insight of soul. Generally, “darśanas” mean critical expositions, logical surveys, or systems. We do not find the word used in this reference in the early stages of philosophical thought, when philosophy was more intuitional. It shows that “darśanas” is not an intuition, however much it may be allied to it. Perhaps the word is advisedly used, to indicate a thought system acquired by intuitive experience and sustained by logical argument. In the systems of extreme monism philosophy prepares the way for intuitional experience by giving us an idea of the impotence of thought. In the systems of moderate monism, where the real is a concrete whole, philosophy succeeds at best in giving an ideal reconstruction of reality. But the real transcends, surrounds and overflows our miserable categories. In extreme monism it is intuitional experience that reveals to us the fullness of reality ; in concrete monism, it is insight, where knowledge is penetrated by feeling and emotion. Conceptual constructions do not possess the certainty of experienced facts. Again, an opinion or

---------------

1. Cf. Bradley, who says that we can reach reality through a kind of feeling, and McTaggart, who looks upon love as the most satisfactory way of characterising the absolute.

44

logical view becomes truth only if it stands the test of life.

“Darśana” is a word which is conveniently vague, as it stands for a dialectical defence of extreme monism as well as the intuitional truth on which it is based. Philosophically “darśana” is putting the intuition to proof and propagating it logically. Even in other systems it applies to the logical exposition of the truth that could be had in conceptual terms with or without the aid of any vivifying intuition. “Darśana” so applies to all views of reality taken by the mind of man, and if reality is one, the different views attempting to reveal the same must agree with each other. They cannot have anything accidental or contingent, but must reflect the different view-points obtained of the one real. By a close consideration of the several views our mind gets by snap-shotting reality from different points, we rise to the second stage of a full rendering of reality in logical terms. When we realise the inadequacy of a conceptual account to reality, we try to seize the real by intuition, where the intellectual ideas are swallowed up. It is then that we are said to get the pure “being” of extreme monism from which we get back to the logical real of thought, which again we begin to spell letter by letter in the different systems themselves. “ Darśana ” as applicable to this last means any scientific account of reality. It is the one word that stands for all the complex inspiration of philosophy by its beautiful vagueness.

The darśana–śāstra, source: bhaktivinodainstitute.org, access date: May 22, 2021.

A “ darśana ” is a spiritual perception, a whole view revealed to the soul sense. This soul sight, which is possible only when and where philosophy is lived, is the distinguishing mark of a true philosopher. So the highest triumphs of philosophy are possible only to those who have achieved in themselves a purity of soul. This purity is based upon a profound acceptance of experience, realised only when some point of hidden strength within man, from which he can not only inspect but comprehend life, is found. From this inner source the philosopher reveals to us the truth of life, a truth which mere intellect is unable to discover. The vision is produced almost as naturally as a fruit from a flower out of the mysterious centre where all experience is reconciled.

1.

2.

45

The seeker after truth must satisfy certain essential conditions before he sets out on his quest. Śaṁkara, in his commentary on the first Sūtra of the Vedānta Sūtras, makes out that four conditions are essential for any student of philosophy. The first condition is a knowledge of the distinction between the eternal and the non-eternal. This does not mean full knowledge, which can come only at the end, but only a metaphysical bent which does not accept all it sees to be absolutely real, a questioning tendency in the inquirer. He must have the inquiring spirit to probe all things, a burning imagination which could extract a truth from a mass of apparently disconnected data, and a habit of meditation which will not all his mind to dissipate itself. The second condition is the subjugation of the desire for the fruits of action either in the present life or a future one. It demands the renunciation of all petty desire, personal motive and practical interest. Speculation or inquiry to the reflective mind is its own end. The right employment of intellect is understanding the things, good as well as bad. The philosopher is a naturalist who should follow the movement of things without exaggerating the good or belittling the evil on behalf of some prejudice of his. He must stand outside of life and look on it. So it is said that he must have on love of the present or the future. Only then can he stake his all on clear thinking and honest judgement and develop an impersonal cosmic outlook with devotedness to fact. To get this temper he must suffer a change of heart, which is insisted on in the third condition, where the student is enjoined to acquire tranquillity, self-restraint, renunciation, patience, peace of mind and faith. Only a trained mind which utterly controls the body can inquire and meditate endlessly so long as life remains, never for a moment losing sight of the object, never for a moment letting it be obscured by any terrestrial temptation. The seeker after truth must have the necessary courage to lose all for his highest end. So is he required to undergo hard discipline which includes pitiless self-examination will enable the seeker to reach his end of freedom. The desire for mokṣa or release is the fourth condition. The metaphysically minded man who has given

1.

2.

46

up all his desires and trained his mind has only one devouring desire to achieve the end or reach the eternal. The people of India have such an immense respect for these philosophers who glory in the might knowledge and the power of intellect, that they worship them. The prophetic souls who with a noble passion for truth strive hard to understand the mystery of the world and give utterance to it, spending laborious days and sleepless nights, are philosophers in a vital sense of term. They comprehend experience on behalf of mankind, and so the latter are eternally grateful to them.

Hanging Gardens of Babylon, source: worldhistory.org, access date: June 13, 2021

Reverence for the past is another national trait. There is a certain doggedness of temperament, a stubborn loyalty to lose nothing in the long march of the ages. When confronted with new cultures or sudden extensions of knowledge, the Indian does not yield to the temptations of the hour, but holds fast to his traditional faith, importing as much as possible of the new to the old. This conservative liberalism is the secret of the success Indian culture and civilisation. Of the great civilisation of the world, hoary with age, only the Indian still survives. The magnificence of the Egyptian civilisation can be learnt only from the reports of the archæologists and the readings of the hieroglyphics ; the Babylonian Empire, with its marvels of scientific, irrigation and engineering skill, is to-day nothing more than a heap of ruins ; the great Roman culture, with its political institutions and ideas of law and equality, is, to a large extent, a thing of the past. The Indian civilisation, which even at the lowest estimate is 4,000 years old, still survives in its essential features. Her civilisation, dating back to the period of the Vedas, is young and old at the same time. She has been renewing her youth whenever the course of history demanded it. When a change occurs, it is not consciously felt to be a change. It is achieved, and all the time it professes to be only a new name for an old way of thinking. In the Ṛgveda we shall see how the religious consciousness of the Aryan invaders takes noted of the conceptions of the people of the soil. In the Atharva Veda we find that the vaguer cosmic deities are added to the gods of the sky and sun, fire and wind worshipped by the Aryan peoples from the Ganges to the Hellespont. The Upaniṣads are regarded as a revival or

1.

2.

47

rather a realisation of something found already in the Vedic hymns. The Bhagavadgītā professes to sum up the teachings of the Upaniṣads. We have in the Epics the meeting-point of the religious conceptions of the highest import with the early nature worship. To respect the spirit of reverence in man for the ancient makes for the success of the new.1 The old spirit is maintained, though not the old forms. This tendency to preserve the type has led to the fashionable remark that India is immobile. The mind of man never stands still, though it admits of no absolute breach with the past.

This respect for the past has produced a regular continuity in Indian thought, where the ages are bound each to each by natural piety. The Hindu culture is a product of ages of change wrought by hundreds of generations, of which some are long, stale and others short, quick and joyous, where each has added something of quality to the great rich tradition which is yet alive, though it bears within it the marks of the dead past. The career of Indian philosophy has been compared to the course of a stream which, tumbling joyfully from its source among the northern mountain tops, rushes through the shadowy valleys and plains, catching the lesser streams in its imperious current, till it sweeps increased to majesty and serene power through the lands and peoples whose fortunes it affects, bearing a thousand ships on its bosom. Who knows whether and when this mighty stream which yet flows on with tumult and rejoicing will pass into the ocean, the father of all streams ?

There are not wanting Indian thinkers who look upon the whole of Indian philosophy as one system of continuous revelation. They believe that each civilisation is working out some divine thought which is natural to it.2 There is

----------------

1. Cf. “This claim of a new thing to be old is, in varying degrees, a common characteristic of great movements. The Reformation professed to be a return to the Bible, the Evangelical movement in England a return to Gospels, the High Church movement a return to the Early Church. A large element even in the French Revolution, the greatest of all breaches with the past, had for its ideal a return to Roman republican virtue or to the simplicity of the natural man” (Gilbert Murray, Four Stages of Great Religion, p. 58).

2. The Greeks call this special quality of each people their “nature,” and the Indians call it their “dharma.”

1.

2.

48

an immanent teleology which shapes the life of each human race towards some complete development. The several views set forth in India are considered to be the branches of self-same tree. The short cuts and blind alleys are somehow reconciled with the main road of advance to the truth. A familiar way in which the six orthodox systems are reconciled is to say that just as a mother in pointing out the moon to the baby speaks of it as the shining circle at the top of the tree, which is quite intelligible to the child, without mentioning the immense distance separating the earth from the moon which would have bewildered it, even so are different views given to suit the varying weakness of human understanding. The Prabodhacandrodaya, a philosophic drama, states that the six systems of Hindu philosophy are not mutually exclusive, but establish from various points of view the glory of the same uncreate God. They together form the living focus of the scattered rays that the many-faceted humanity reflects from the splendid sun. Mādhava’s Sarvadarśanasaṁgraha (A.D.1380) sketches sixteen systems of thought so as to exhibit a gradually ascending series, culminating in the Advaita Vedānta (or non-dualism). In the spirit of Hegel, he looks upon the history of Indian philosophy as a progressive effort towards a fully articulated conception of the world. The truth is unfolded bit by bit in the successive systems, and complete truth is reflected only when the series of philosophies is completed. In the Advaita Vedānta are the many lights brought to a single focus. Vijñānabhikṣu, the sixteenth-century theologian and thinker, holds that all systems are authoritative,1 and reconciles them by distinguishing practical from metaphysical truth, and looks upon Sāṁkhya as the final expression of truth, Madhusūdana Sarasvatī in his Prasthānabheda writes : “The ultimate scope of all the munis, authors of these different systems, is to support the theory of māyā, and their only design is to establish the existence of one supreme God, the sole essence, for these munis could not be mistaken, since they were omniscient. But as they saw that men, addicted to the pursuit of external objects, could not all at once penetrate into the highest

---------------

1. Sarvāgamaprāmāṇya.

The Cover of The Prabodhacandrodaya, written by Kṛṣṇa Miśra, translated by Dr. Sita K. Nambiar, May 1, 2012, Motilal Banarsidass Printing, Bharat.

The Sarvadarśanasaṁgraha of Mādhavācārya, source: www.amazon.com, access date: May 25, 2025.

The Sarvadarśanasaṁgraha of Mādhavācārya, source: www.amazon.com, access date: May 25, 2025.49

truths, they held out to them a variety of theories in order that they might not fall into atheism. Misunderstanding the object which the munis thus had in view, and representing that they even designed to propound doctrines contrary to the Vedas, men have come to regard the specific doctrines of these several schools with preference, and thus became adherents of a variety of systems.”1 This reconciliation of the several systems,2 is attempted by almost all the critics and commentators. The difference is only about what they regard as the truth. Defenders of Nyāya like Udayana look upon Nyāya, and theists like Rāmānuja consider theism to be the truth. Defenders of Nyāya like Udayana look upon Nyāya, and theists like Rāmānuja consider theism to be the truth. It is in accordance with the spirit of Indian culture to think that the several currents of thought flowing in its soil will discharge their waters into the one river whose flood shall make for the City of God.

From the beginning the Indian felt that truth was many-sided, and different views contained different aspects of truth which no one could fully express. He was therefore tolerant and receptive of other views. He was fearless in accepting even dangerous doctrines so long as they were backed up by logic. He would not allow to die, if he could help it, one jot or tittle of the tradition, but would try to accommodate it all. Several cases of such tolerant treatment we shall meet with in the course of our study. Of course there are dangers incident to such a breath of view. Often it has led the Indian thinkers into misty vagueness, lazy acceptance and cheap eclecticism.

1.

2.

III

SOME CHARGES AGAINST INDIAN PHILOSOPHY

1.

The main charges against Indian philosophy are those of pessimism, dogmatism, indifference to ethics and unprogressiveness.

Almost every critic of Indian philosophy and culture harps on its pessimism.3 We cannot, however, understand

---------------

1. See Muir. O.S.T., iv. 1 and 2.

2. Sarvadarśanasāmrasya.

3. Chailley, in his Administrative Problems (p.67), asserts that Indian philosophy springs “from lassitude and a desire for eternal rest.”

1.

2.

50

How the human mind can speculate freely and remodel life when it is filled with weariness and overcome by a feeling of hopelessness. A priori, the scope and freedom of Indian thought are inconsistent with an ultimate pessimism. Indian philosophy is pessimistic if by pessimism is meant a sense of dissatisfaction with what is or exists. In this sense all philosophy is pessimistic. The suffering of the world provokes the problems of philosophy and religion. Systems of religion which emphasise redemption seek for an escape from life as we live it on earth. But reality in its essence is not evil. In Indian philosophy the same word “sat” indicates both reality and perfection. Truth and goodness, or more accurately reality and perfection, go together. The real is also the supremely valuable, and this is the basis of all optimism. Professor Bosanquet writes : “I believe in optimism, but I add that no optimism is worth its salt that does not go all the way with pessimism and arrive at a point beyond it. This, I am convinced, is the true spirit of life ; and if any one thinks it dangerous, and an excuse for unjustifiable acquiescence in evil, I reply that all truth which has any touch of thoroughness has its danger for practice.”1 Indian thinkers are pessimistic in so far as they look upon the world order as an evil and a lie ; they are optimistic since they feel that there is a way out of it into the realm of truth, which is also goodness.

Indian philosophy, it is said, is nothing if not dogmatic, and true philosophy cannot subsist with the acceptance of dogma. The course of our study of Indian thought will be an answer to this charge. Many of the systems of philosophy discuss the problem of knowledge, its origin, and validity as a preliminary to a study of other problems. It is true that the Veda or the śruti is generally considered to be an authoritative source of knowledge. But a philosophy becomes dogmatic only if the assertions of the Veda are looked upon as superior to the evidence of the senses and the conclusions of reason.

---------------

1. Social and International Ideals, p.43. Cf. Schopenhauer: “Optimism, when it is not merely the thoughtless talk of such as harbour nothing but words under their low foreheads, appears not merely as an absurd but also as a really wicked way of thinking, as a bitter mockery of the unspeakable suffering humanity.”

1.

2.

51

The Vedic statements are āptavacana, or sayings of the wise, which we are called upon to accept, if we feel convinced that those wise had better means than we have of forming a judgment on the matter in question. Generally, these Vedic truths refer to the experiences of the seers, which any rational rendering of reality must take into account. These intuitional experiences are within the possibility of all men if only they will to have them.1 The appeal to the Vedas does not involve any reference to an extra-philosophical standard. What is dogma to the ordinary man is experience to the pure in heart. It is true that when we reach the stage of the later commentaries we have a state of philosophical orthodoxy, when speculation becomes an academic defence of accepted dogmas. The earlier systems also call themselves exegetical and profess to be commentaries on the old texts, but they never tended to become scholastic, since the Upaniṣads to which they looked for inspiration were many-sided.2 After the eighth century philosophical controversy became traditional and scholastic in character, and we miss the freedom of the earlier era. The founders of the schools are canonised, and so questioning their opinions is little short of sacrilege and impiety. The fundamental propositions are settled once for all, and the function of the teacher is only to transmit the beliefs of the school with such changes as his brain can command and the times require. We have fresh arguments for foregone conclusions, new expedients to meet new difficulties and a re-establishment of the old with a little change of front or twist of dialectic. There is less of meditation on the deep problems of life and more of discussion of the artificial ones. The treasure that is the tradition clogs us with its own burdensome wealth, and philosophy ceases to move and sometimes finds it hard to breathe at all. The charge of unprofitableness urged in general against the whole of Indian philosophy may have some point when applied to the wordy disquisitions of the commentators who are not the inspired apostles of life and beauty which the older generation of philosophers were, but professional dialecticians conscious of their mission to mankind. Yet even under the inevitable crust of age the

---------------

1. See S.B.V.S., iii. 2. 24.

2. Viśvatomukhāḥ.

1.

2.

52

soul remains young, and now and then breaks through and sprouts into something green and tender. There arise men like Śaṁkara or Mādhava, who call themselves commentators, and yet perceive the spiritual principle which directs the movements of the world.

It is often urged against Indian philosophy that it is nonethical in character. “There is practically no ethical philosophy within the frontiers of Hindu thinking.”1 The charge, however, cannot be sustained. Attempts to fill the whole of life with the power of spirit are common. Next to the category of reality, that of dharma is the most important concept in Indian thought. So far as the actual ethical content is concerned, Buddhism, Jainism and Hinduism are not inferior to others. Ethical perfection is the first step towards divine knowledge.

Source: https://storylog.co/story/590d83323a2d222a22214e2e, access date: November 10, 2021.

1.

Philosophy in India, it is said, remains stationary and represents an endless process of threshing old straw. “The unchanging East” connotes that in India time has ceased to fly and remained motionless for ever. If it means that there is a fundamental identity in the problems, then this sort of unprogressiveness is a feature common to all philosophical developments. The same old problems of God, freedom and immortality and the same old unsatisfactory solutions are repeated throughout the centuries. While the form of the problems is the same, the matter has changed. There is all the difference in the world between the God of the Vedic hymns drinking soma, and the Absolute of Śaṁkara. The situations to which philosophy is a response renew themselves in each generation, and the effort to deal with them needs a corresponding renewal. If the objection means that there is not much fundamental difference between the solutions given in the ancient scriptures of India and Plato’s works of Christian writings, it only shows that the same loving universal Spirit has been uttering its message and making its voice heard from time to time. The sacred themes come down to us through the ages variously balanced and coloured by race and tradition. If it means that there is a certain reverence for the past which impels the Indian thinkers to pour new wine into old bottles, we have already said that this

---------------

1. Farquhar, Hibbert Journal, October 1921, p.24.

1.

2.

53

is a characteristic of the Indian mind. The way to grow is to take in all the good that has gone before and add to it something more. It is to inherit the faith of the fathers and modify it by the spirit of the time. If Indian thought is said to be futile because it did not take into account the progress of the sciences, it is the futility which all old things possess in the eyes of the new. The scientific developments have not brought about as great a change in the substance of philosophy as this criticism assumes. The theories so revolutionary in their scientific aspects as the biological evolution and the physical relativity have not upset established philosophies, but only confirmed them from fresh fields.

The charge of unprogressiveness or stationariness holds when we reach the stage after the first great commentators. The hand of the past grew heavy, initiative was curbed, and the work of the scholastics, comparable to that of the mediæval Schoolmen, with the same reverence for authority and tradition and the same intrusion of theological prejudice, began. The Indian philosopher could have done better with greater freedom. To continue the living development of philosophy, to keep the current of creative energy flowing, contact with the living movements of the world capable of promoting real freedom of thought is necessary. Perhaps the philosophy of India which lost its strength and vigour when her political fortunes met with defeat may derive fresh inspiration and a new impulse from the era just dawning upon her. If the Indian thinkers combine a love of what is old with a thirst for what is true, Indian philosophy may yet have a future as glorious as its past.

1.

2.

IV

VALUE OF THE STUDY OF INDIAN PHILOSOPHY

1.

It is not merely as a piece of antiquarian investigation that Indian thought deserves study. Speculations of particular thinkers or the ideas of a past age are not without value. Nothing that has ever interested men and women can ever wholly lose its vitality. In the thought of the Vedic Aryans we witness the wrestlings of powerful minds

1.

2.

54

with the highest problems set to thinking man. In the words of Hegel: “The history of philosophy in its true meaning deals not with the past, but with the eternal and veritable present ; and in its results resembles, not a museum of aberrations of the human intellect, but a pantheon of Godlike figures representing various stages of the immanent logic of all human thought.”1 The history of Indian thought is not what it seems at first sight, a mere succession of ghostly ideas which follow one another in rapid succession.

It is easy to make sport of philosophy, since to those who are content to live among the things of sense and think in a slovenly way, philosophic problems wear a look of unreality, and possess a flavour of absurdity. The hostile critic looks upon the disputes of philosophy as wasteful logic-chopping and intellectual legerdemain concerned with such conundrums as “Did the hen come first or the egg?”2 The problems discussed in Indian Philosophy have perplexed men from the beginning of time, though they have never been solved to the satisfaction of all. There seems to be an essential human need or longing to know the nature of soul and God. Every thinking man, when he reflects on the fact that he is swept without pause along the great curve of birth to death, the rising flood of life, the ceaseless stream of becoming, which presses ever onward and upward, cannot but ask, What is the purpose of it all, as a whole, apart from but ask, What is the purpose of it all, as a whole, apart from the little distracting incidents of the way? Philosophy is no racial idiosyncrasy of India, but a human interest.

If we lay aside professional philosophy, which may well be a futile business, we have in India one of the best logical developments of thought. The labours of the Indian thinkers are so valuable to the advancement of human knowledge that we judge their work to be worthy of study, even if we find manifest errors in it. If the sophisms which ruined the philosophy should be given up. After all, the residuum of permanent truth which may be acknowledge as the

---------------

1. Logic, p. 137. , Wallace’s translation.

2. After all, this question is not so trite or innocent as it appears to be. See Samuel Butler’s Luck or Cunning.

1.

2.

55

effective contribution to human thought even with regard to the most illustrious thinkers of the West, like Plato and Aristotle, is not very great. It is easy to smile at the exquisite rhapsodies of Plato or the dull dogmatism of Descartes or the arid empiricism of Hume or the bewildering paradoxes of Hegel, and yet withal there is no doubt that we profit by study of their works. Even so, though only a few of the vital truths of Indian thinkers have moulded the history of the human mind, yet there are general syntheses, systematic conceptions put forward by a Bādarāyaṇa or Śaṁkara which will remain landmarks of human thought and monuments of human genius.1

To the Indian student study of Indian philosophy alone can give a right perspective about the past of India. At the present day the average Hindu looks upon his past systems, Buddhism, Advaitism, Dvaitism, as all equally worthy and acceptable to reason. The authors of the systems are worshipped as divine. A study of Indian philosophy will conduce to the clearing up of the situation, the adopting of a more balanced outlook and the freeing of the mind from the oppressing sense of the perfection of everything that is ancient. This freedom from bondage to authority is an ideal worth striving at. For when the enslaved intellect is freed, original thinking and creative effort might again be possible. It may be a melancholy satisfaction to the present day Indian

---------------

1. Many scholars of the West recognise the value of Indian philosophy. “On the other hand, when we read with attention the poetical and philosophical movements of the East, above all those of India, which are beginning to spread in Europe, we discover there so many truths, and truths so profound, and which make such a contrast with the meanness of the results at which the European genius has sometimes stopped, that we are constrained to bend the knee before that of the East, and to see in this cradle of the human race the native land of the highest philosophy” (Victor Cousin). “If I were to ask myself from what literature, we here in Europe, we who have been nurtured almost exclusively on the thoughts of Greeks and Romans, and of one Semitic race, the Jewish, may draw that corrective which is most wanted, in order to make our inner life more perfect, more comprehensive, more universal, in fact more truly human, a life, not for this life only, but a transfigured and eternal life – again, I should point to India” (Max Müller). “Among nations possessing indigenous philosophy and metaphysics, together with an innate relish for these pursuits, such as at present characterises Germany, and in olden times was the proud distinction of Greece, Hindustan holds the first rank in point of time” (Ibid.).

Friedrich Max Müller (German: 6 December 1823 – 28 October 1900) was a German-born philologist and Orientalist, source: sriramakrishna.in, access date: 27 November 2021

Friedrich Max Müller (German: 6 December 1823 – 28 October 1900) was a German-born philologist and Orientalist, source: sriramakrishna.in, access date: 27 November 2021

1.

2.

56

to know some details of his country’s early history. Old men console themselves with the stories of their youth, and the way to forget the bad present is to read about the good past.

1.

2.

V

PERIODS OF INDIAN THOUGHT

1.

It is necessary to give some justification for the title “Indian Philosophy,” when we are discussing the philosophy of the Hindus as distinct from that of the other communities which have also their place in India. The most obvious reason is that of common usage. India even to-day is mainly Hindu. And we are concerned here with the history of Indian thought up till A.D.1000 or a little after, when the fortunes of the Hindus became more and more linked with those of the non-Hindus.

To the continuous development of Indian thought different peoples at different ages have brought their gifts, yet the force of the Indian spirit had its own shaping influence on them. It is not possible for us to be sure of the exact chronological development, though we shall try to view Indian thought from the historical point of view. The doctrines of particular schools are relative to their environment and have to be viewed together. Otherwise, they will cease to have any living interest for us and become dead traditions. Each system of philosophy is an answer to a positive question which its age has put to itself, and when viewed from its own angle of vision will be seen to contain some truth. The philosophies are not sets of propositions conclusive or mistaken, but the expression and evolution of a mind with which and in which we must live if we wish to know how the systems shaped themselves. We must recognise the solidarity of philosophy with history, of intellectual life with the social conditions.1 The historical method requires us not to take

---------------

1. In the image of Walter Pater. “As the strangely twisted pine-tree, which would be a freak of nature on an English lawn, is seen, if we replace it in thought, amid the contending forces of the Alpine torrent that actually shaped its growth, to have been the creature of necessity, of the logic of propriety when they are duly correlated with the conditions round them of which they are in truth a part” (Plato and Platonism, p. 10).

1.

2.

57

sides in the controversy of schools, but follow the development with strict indifference.

While we are keenly alive to the immense importance of historical perspective, we regret that on account of the almost entire neglect of chronological sequences of the writings it is not possible for us to determine exactly the relative dates of the systems. So unhistorical, or perhaps so ultra-philosophical, was the nature of the ancient Indian, that we know more about the philosophies than about the philosophers. From the time of the birth of Buddha Indian chronology is on a better foundation. The rise of Buddhism was contemporaneous with the extension of the Persian power to the Indus under the dynasty of Achæmenidæ in Persia. It is said to be the source of the earliest knowledge of India in the West obtained by Hecateus and Herodotus.

The following are the broad divisions of Indian philosophy :

(1) The Vedic Period (1500 B.C.-600 B.C.) covers the age of the settlement of the Aryans and the gradual expansion and spread of the Aryan culture and civilisation. It was the time which witnessed the rise of the forest universities, where were evolved the beginnings of the sublime idealism of India. We discern in it successive strata of thought, signified by the Mantras of the hymns, the Brāhmaṇas, and the Upaniṣads. The views put forward in this age are not philosophical in the technical sense of the term. It is the age of grouping, where superstition and thought are yet in conflict. Yet to give order and continuity to the subject, it is necessary for us to begin with an account of the outlook of the hymns of the Ṛg-Veda and discuss the views of the Upaniṣads.

(2) The Epic Period (600 B.C. to A.D. 200) extends over the development between the early Upaniṣads and the darśanas or the systems of philosophy. The epics of the Rāmāyaṇa and the Mahābhārata serve as the vehicles through which was conveyed the new message of the heroic and the godly in human relations. In this period we have also the great democratisation of Upaniṣads ideas in Buddhism and Bhagavadgītā. The religious systems of Buddhism, Jainism, Śaivism, Vaiṣṇavism belong to this age. The development of abstract thought which culminated

1.

2.

58

in the schools of Indian philosophy, the darśanas, belongs to this period. Most of the systems had their early beginnings about the period of the rise of Buddhism, and they developed side by side through many centuries ; yet the systematic works of the schools belong to later age.

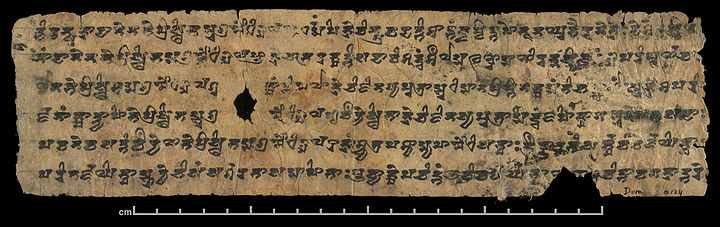

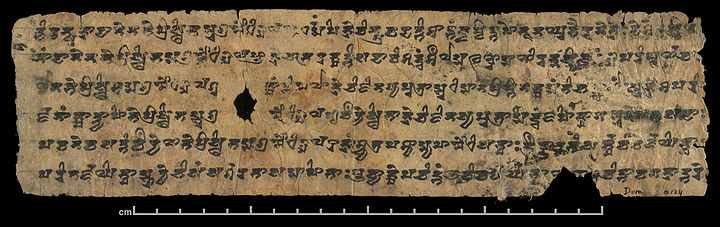

A Sanskrit manuscript page of Lotus Sutra (Buddhism) from South Turkestan in Brahmi script, source: en.wikipedia.org, access date: Dec 4, 2021.

A Sanskrit manuscript page of Lotus Sutra (Buddhism) from South Turkestan in Brahmi script, source: en.wikipedia.org, access date: Dec 4, 2021.1.

(3) The Sūtra Period (from A.D. 200) comes next. The mass of material grew so unwieldy that it was found necessary to devise a shorthand scheme of philosophy. This reduction and summarisation occurred in the form of Sūtras. These Sūtras are unintelligible without commentaries, so much so that the latter have become more important than the Sūtras themselves. Here we have the critical attitude in philosophical discussions, no doubt, where the mind did not passively receive whatever it was told, but played round the subject, raising objections and answering them. By happy intuition the thinkers pitch upon some general principles which seem to them to explain all aspects of the universe. The philosophical syntheses, however profound and acute they may be, suffered throughout from the defect of being pre-critical, in the Kantian sense of the term. Without a previous criticism of human capacity to solve philosophical problems, the mind looked at the world and reached its conclusions. The earlier efforts to understand and interpret the world were not strictly philosophical attempts, since they were not troubled by any scruples about the competence of the human mind or the efficiency of the instruments and the criteria employed. As Caird puts it, mind was “too busy with the object to attend to itself.”1 So when we come to the Sūtras we have thought and reflection become self-conscious freedom. Among the systems themselves, we cannot say definitely which are earlier and which later. There are cross-references throughout. The Yoga accepts the Sāṁkhya, Vaiśeṣika recognises both the Nyāya and the Sāṁkhya. Nyāya refers to the Vedānta and the Sāṁkhya. Mīmāṁsā directly or indirectly recognises the pre-existence of all others. So does the Vedānta. Professor Garbe holds that the Sāṁkhya is the oldest school. Next

---------------

1. Critical Philosophy of Kant, vol. i. p. 2

1.

2.

59

came Yoga, next Mīmāṁsā and Vedānta, and last of all Vaiśeṣika and Nyāya. The Sūtra Period cannot be sharply distinguished from the scholastic period of the commentators. The two between them extend up till the present day.

(4) The Scholastic Period also dates from the second century A.D. It is not possible for us to draw a hard and fast line between this and the previous one. Yet it is to this that the great names of Kumārila, Śaṁkara, Śrīdhara, Rāmānuja, Madhva, Vācaspati, Udayana, Bhāskara, Jayanta, Vijñānabhikṣu and Raghunātha belong. The literature soon becomes grossly polemical. We find a brood of schoolmen, noisy controversialists indulging in over-subtle theories and fine-spun arguments, who fought fiercely over the nature of logical universals. Many Indian scholars dread opening their tomes which more often confuse than enlighten us. None would deny their acuteness and enthusiasm. Instead of thought we find words, instead of philosophy logic-chopping. Obscurity of thought, subtlety of logic, intolerance of disposition, mark the worst type of the commentators. The better type, of course, are quite as valuable as the ancient thinkers themselves. Commentators like Śaṁkara and Rāmānuja re-state the old doctrine, and their restatement is just as valuable as a spiritual discovery.

There are some histories of Indian philosophy written by Indian thinkers. Almost all later commentators from their own points of view discuss other doctrines. In that way every commentator happens to give an idea of the other views. Sometimes conscious attempts are made to deal with the several systems in a continuous manner. Some of the chief of these “historical” accounts may here be mentioned. Ṣaḍdarśanasamuccaya, or the epitome of the six systems, is the name of a work by Haribhadra.1

---------------

श्रीधर - Śrīdhara or श्रीधर आचार्य - Śrīdhara Ācāryya, sources: https://x.com/desi_thug1/status/1590898621452804097, access date: July 5, 2025.

1.

Bhāskara, source: despee.com, access date: July 6, 2025.

Bhāskara, source: despee.com, access date: July 6, 2025.

Haribhadra, source: thestupa.com, access date: Dec.6, 2021.

Haribhadra, source: thestupa.com, access date: Dec.6, 2021.1.

1. Mr. Barth says: “Haribhadra, who according to tradition died in A.D. 529, but by more exact testimony lived in the ninth century, and who had several homonyms, was a Brāhmin converted to Jainism. He is famous still as the author of Fourteen Hundred Prabandhas (chapters of works), and seems to have been one of the first to introduce the Sanskrit language into the scholastic literature of the Śvetāmbara Jains. By the six systems the Brāhmins understand the two Mīmāṁsās, the Sāṁkhya and the Yoga, the Nyāya and the Vaiśeṣika. Haribhadra, on the other hand, expounds under this title very curtly in eighty-seven slokas, but quite impartially, the essential principles of the Buddhists, the Jainas, the followers of the Nyāya,

1.

2.

60

Samantabhadra01, a Digambara Jain of the sixth century, is said to have written a work called Āptamīmāṁsā, containing a review of the various philosophical schools.1 A Mādhyamika Buddhist, by name Bhāvaviveka, is reputed to be the author of a work called Tarkajvāla, a criticism of the Mīmāṁsā, Sāṁkhya, Vaiśeṣika, and Vedānta schools. A Digambara Jain, by name Vidyānanda, in his Aṣṭasāhasrī, and another Digambara, by name Merutuṅga, in his work on Ṣaḍdarśanavicāra (1300 A.D.) are said to have criticised the Hindu systems. The most popular account of Indian philosophy is the Sarvadarśanasaṁgraha, by the well-known Vedāntin Mādhavācārya, who lived in the fourteenth century in South India. The Sarvasiddhāntasārasaṁgraha assigned to Śaṁkara,2 and the Prasthānanabheda by Madhusūdana Sarasvatī,3 contain useful accounts of the different philosophies.

---------------

Notes:

Samantabhadra (समन्तभद्र), source: www.reddit.com, access date: July 8, 2025.

1.

01. Samantabhadra (समन्तभद्र) see page 2 of Mahayana, Buddhism Chapter 2.

---------------

the Sāṁkhya, the Vaiśeṣika, and the Mīmāṁsā. He thus selects his own school and those with whom the Jainas had the closest affinities, and puts them between the schools of their greatest enemies, the Buddhists and the ritualists of the school of Jaimini. These last he couples with the Lokāyatikas, the atheistic materialists, not simply from sectarian fanaticism and on his own judgment, but following an opinion that was then prevalent even among the Brāhmins” (Indian Antiquary, p. 66, 1895).

1. Vidyabhushan, Mediæval Systems of Indian Logic, pp. 23.

2. The ascription seems to be incorrect. See Keith: Indian Logic, p. 242, n. 3.

3. See Max Müller, Six Systems, pp. 75 to 84.

1.

2.

3.