Title Thumbnail: Arjun and Krishna encounter with Karna, circa 1820 source: Philadelphia Art Museum, accessed date: Sep.21, 2017, Hero Image: Spiritual Nonviolence, source: www.pinterest.com, access date: Mar.11, 2021.

Indian Philosophy Volume 2.001

First revision: Jan.11, 2021

Last change: Sep.02, 2021

16

PART III

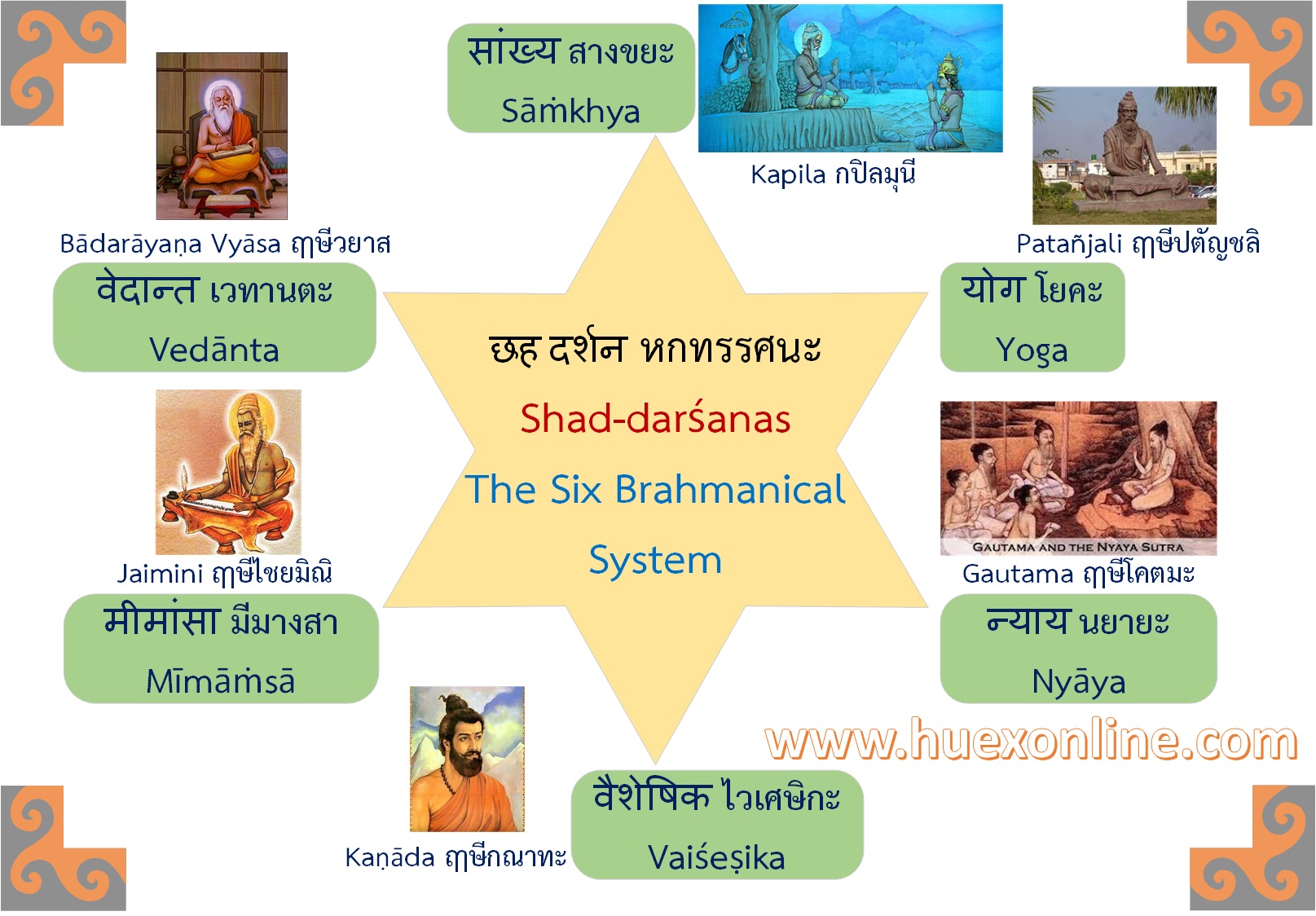

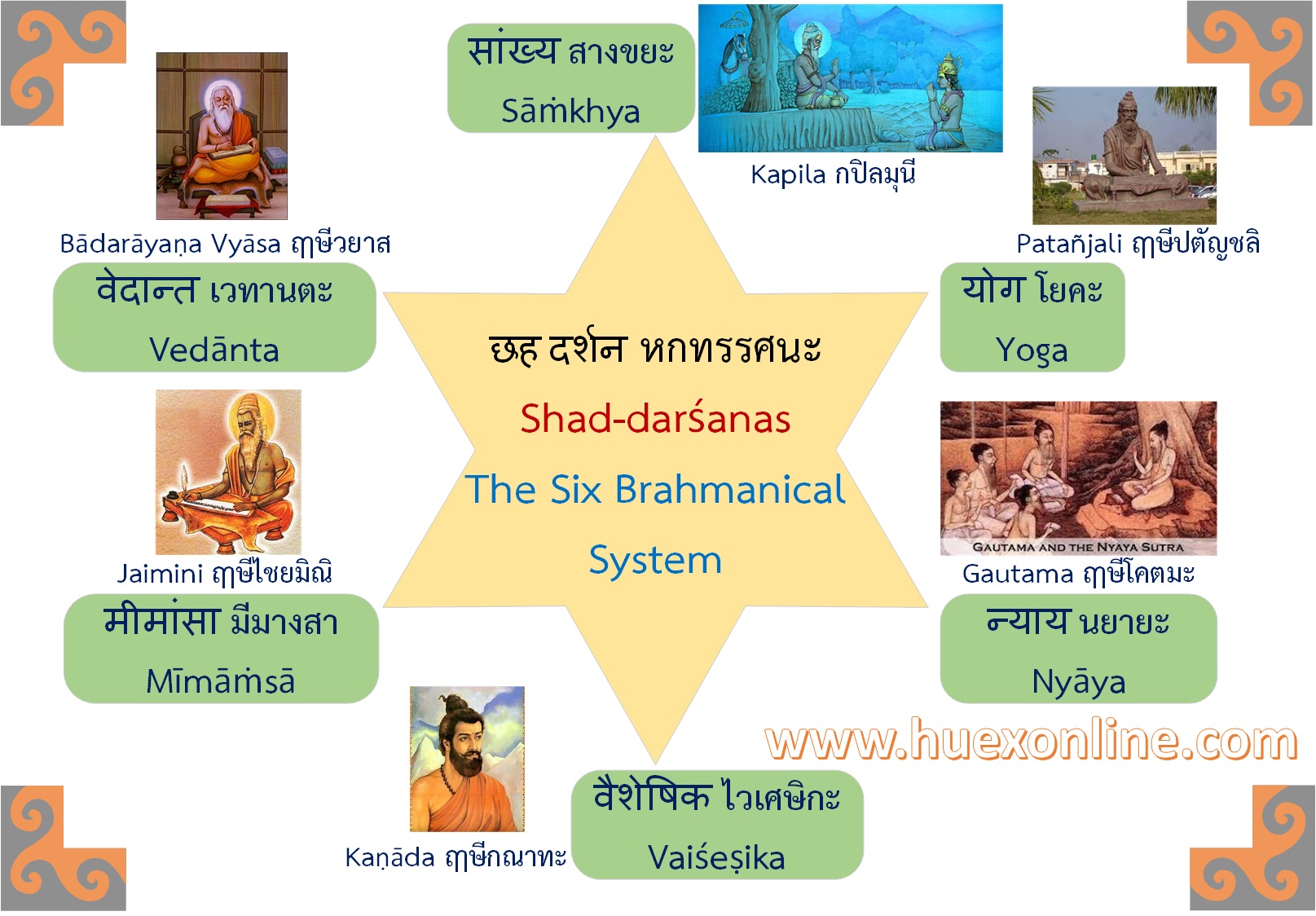

THE SIX BRAHMANICAL SYSTEMS

17

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

The spirit of the age – The Darśanas – Āstika, and Nāstika – Sūtra literature – Date – Common ideas – The six systems.

I

THE RISE OF THE SYSTEMS

THE age of Buddha represents the great springtide of philosophic spirit in India. The progress of philosophy is generally due to a powerful attack on a historical tradition when men feel themselves compelled to go back on their steps and raise once more the fundamental questions which their fathers had disposed of by the older schemes. The revolt of Buddhism and Jainism, even such as it was, forms an era in the history of Indian thought, since it finally exploded the method of dogmatism and helped to bring about a critical point of view. For the great Buddhist thinkers, logic was the main arsenal where were forged the weapons of universal destructive criticism. Buddhism served as a cathartic in cleaning the mind of the cramping effects of ancient obstructions. Scepticism, when it is honest, helps to reorganised belief on its natural foundations. The need for laying the foundations deeper resulted in the great movement of philosophy which produced the six systems of thought, where cold criticism and analysis take the place of poetry and religion. The conservative schools were compelled to codify their views and set forth logical defences of them. The critical side of philosophy became as important as the speculative. The philosophical views of the presystematic period set forth some general

18

Reflections regarding the nature of the universe as a whole, but did not realise that a critical theory of knowledge is the necessary basis of any fruitful speculation. Critic forced their opponents to employ the natural methods relevant to life and experience, and not some supernatural revelation, in the defence of their speculative schemes. We should not lower our standards to let in the beliefs we wish to secure. Ātmavidyā or philosophy is now supported by Ānvīkṣikī or the science of inquiry.1 A rationalistic defence of philosophic systems could not have been very congenial to the conservative mind.2 To the devout it must have appeared that the breath of life had departed since intuition had given place to critical reason. The force of thought which springs straight from life and experience as we have it in the Upaniṣads, or the epic greatness of soul which sees and chants the God-vision as in the Bhagavadgītā give place to more strict philosophizing. Again, when an appeal to reason is admitted, one cannot be sure of the results of thought. A critical philosophy need not always be in conformity with cherished traditions. But the spirit of the times required that every system of thought based on reason should be recognized as a darśana. All logical attempts to gather the floating conceptions of the world into some great general ideas were regarded as darśanas.3 They all help us to see some aspect of the truth. This conception led to the view that the apparently isolated and independent systems were really

---------------

1 N.B., i. I. I. ; Manu, vii. 43. Kauṭilya (about 300 B.C.) asserts that Ānvīkṣikī is a distinct branch of study over and above the other three, Trayī or the Vedas, Vārtā or commerce, and Daṇḍanīti or polity (I, 2). The sixth century B.C., when it was recognised as a special study, marks the beginning of systematic philosophy in India, and by the first century B.C. the term Ānvīkṣikī is replaced by “darśana” (see M.B., Śāntiparva, 10. 45 ; Bhāgavata Purāṇa, viii. 14. 10). Every inquiry starts in doubt and fulfils a need. Cp. Jijñāsayā saṁdehaprayojane sūcayati (Bhāmatī, i. I. I).

2 In the Rāmāyaṇa, Ānvīkṣikī is censured as leading men away from the injunctions of the dharmaśāstras (ii. 100. 36) (M.B., Śānti, 180. 47-49 ; 246-8). Manu holds that those who misled by logic (hetuśāstra) disregard the Vedas and the Dharma Sūtras deserve excommunication (ii. II) ; yet course of Ānvīkṣikī for kings. Logicians were included in the legislative assemblies. When logic supports scripture, it is commended. By means of Ānvīkṣikī, Vyāsa claims to have arranged the Vedas (Nyāyasūtravṛtti, I, I. I).

3 Mādhava : S.D.S.

19

Great Brahmana-Hindu Sage was developed on July 31, 2024.II

RELATION TO THE VEDAS

The adoption of the critical method served to moderate the impetuosity of the speculative imagination and helped to show that the pretended philosophies were not so firmly held as their professors supported. But the iconoclastic fervour of the materialists, the sceptics and some followers of Buddhism destroyed all grounds of certitude. The Hindu mind did not contemplate this negative result with equanimity. Man cannot live on doubt. Intellectual pugilism is not sufficient by itself. The zest of combat cannot feed the spirit of man. If we cannot establish through logic the truth of anything, so much the worse for logic. It cannot be that the hopes and aspirations of sincere souls like the ṛṣis of the Upaniṣads are irrevocably doomed. It cannot be that centuries of struggle and thought have not brought the mind one step nearer to the solution. Despair is not the only alternative. Reason assailed could find refuge in faith. The seers of the Upaniṣads are the great teachers in the school of sacred wisdom. They speak to us of the knowledge of God and spiritual life. If the unassisted reason of man cannot attain any hold on reality by means of mere speculation, help may be sought from the great writings of the seers who claim to have attained spiritual certainty. Thus strenuous attempts were made to justify by reason what faith implicitly accepts. This is not an irrational attitude, since philosophy is only an endeavour to interpret the widening experience of humanity. The one danger that we have to avoid is lest faith should furnish the conclusions for philosophy.

Of the systems of thought or darśanas, six became more famous than others, viz., Gautama’s Nyāya, Kaṇāda’s Vaiśeṣika, Kapila’s Sāṁkhya, Patañjali’s Yoga, Jaimini’s Pūrva Mīmāṁsā

20

and Bādarāyaṇa’s Uttara Mīmāṁsā or the Vedānta.1 They are the Brahmanical systems, since they all accept the authority of the Vedas

--------------

1Haribhadra, in his Ṣaḍdarśanasamuccaya, discusses the Buddhist, discusses the Buddhist, the Naiyāyikas, and the Sāṁkhya, the Jaina, the Vaiśeṣika, and the Jaiminīya systems (i. 3). Jinadatta and Rājaśekhara agree with this view.