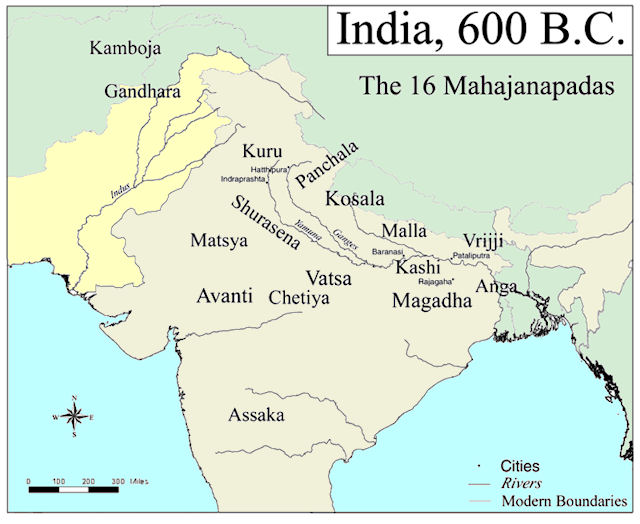

Title Thumbnail: India, 600 B.C. "The 16 Mahajanapadas," source: globalsecurity.org, access date: Jan.22, 2021.

Hero Image: Mahājanapada Period c.500 BCE, source: en.wikipedia.org, access date: March 16, 2018.

Indian Philosophy Volume 1.001 - Introduction

First revision: Jan.11, 2021

Last change: Apr.29, 2025

Searched, Gathered, Rearranged, Translated, and Compiled by Apirak Kanchanakongkha.

INDIAN PHILOSOPHY

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

General characteristics of Indian philosophy – The natural situation of India – The dominance of the intellectual interest – The individuality of Indian philosophy – The influence of the West – The spiritual character of Indian thought – Its close relation to life and religion – The stress on the subjective – Psychological basis of metaphysics – Indian achievements in positive science – Speculative synthesis and scientific analysis – The brooding East – Monistic idealism – Its varieties, non-dualism, pure monism, modified monism and implicit monism – God is all-The intuitional nature of philosophy – Darśana - Śaṁkara’s qualifications of a candidate for the study of Philosophy – The constructive conservatism of Indian thought – The unity and continuity of Indian thought – Consideration of some charges levelled against Indian philosophy, such as pessimism, dogmatism, indifference to ethics and unprogressive character – The value of the study of Indian philosophy – The justification of the title “Indian Philosophy” – Historical method – The difficulty of a chronological treatment – The different periods of Indian thought – Vedic, epic, systematic and scholastic – “Indian” histories of Indian philosophy.

I

THE NATURAL SITUATION OF INDIA

For Thinking minds to blossom, for arts and sciences to flourish, the first condition necessary is a settled society providing security and leisure. A rich culture is impossible with a community of nomads, where people struggle for life and die of privation. Fate called India to a spot where nature was free with her gifts and every prospect was pleasing. The Himalayas, with their immense range and elevation on one side and the sea on the others, helped to keep India free from invasion for a long time. Bounteous nature

India, 600 B.C. "The 16 Mahajanapadas", source: globalsecurity.org, access date: Jan.22, 2021.

22

yield abundant food, and man was relieved of the toil and struggle for existence. The Indian never felt that the world was a field of battle where men struggle for power, wealth and domination. When we do not need to waste our energies on problems of life on Earth, exploiting nature and controlling the forces of the world, we begin to think of the higher life, how to live more perfectly in the spirit. Perhaps an enervating climate inclined the Indian to rest and retirement. The huge forests with their wide leafy avenues afforded great opportunities for the devout soul to wander peacefully through songs. World-weary men go out on pilgrimages to these scenes of nature, acquire inward peace, listening to the rush of winds and torrents, the music of birds and leaves, and return whole of heart and fresh in spirit. It was in the āśramas and tapovanas or forest hermitages that the thinking men of India mediated on the deeper problems of existence, and the absence of a tyrannous practical interest, stimulated the higher life of India, with the result that we find from the beginnings of history an impatience of spirit, a love of wisdom and a passion for the saner pursuits of the mind.

Helped by natural conditions, and provided with intellectual scope to think out the implications of things, the Indian escaped the doom which Plato pronounced to be the worst of all, viz. the hatred of reason. “Let us above all things take heed,” says he in the Phædo, “that one misfortune does not befall us. Let us not become misologues as some people become haters of reason.” The pleasure of understanding is one of the purest available to man, and the passion of the Indian for it burns in the bright flame of the mind.

In many other countries of the world, reflection on the nature of existence is a luxury of life. The serious moments are given to action, while the pursuit of philosophy comes up as a parenthesis. In ancient India philosophy comes up as a parenthesis. In ancient India philosophy was not an auxiliary to any other science or art, but always held a prominent position of independence. In the West, even

23

in the heyday of its youth, as in the times of Plato and Aristotle, it learned for support on some other study, as politics or ethics. It was theology for the Middle Ages, natural science for Bacon and Newton, history, politics and sociology for the nineteenth-century thinkers. In India philosophy stood on its own legs, and all other studies looked to it for inspiration and support. It is the master science guiding other sciences, without which they tend to become empty and foolish. The Muṇḍaka Upaniṣad speaks of Brahma-vidyā or the science of the eternal as the basis of all sciences, sarva-vidyā-pratiṣṭhā. “Philosophy,” says Kauṭilya, “is the lamp of all the sciences, the means of performing all the works, and the support of all the duties.”1

Since philosophy is a human effort to comprehend the problem of the universe, it is subject to the influences of race and culture. Each nation has its own characteristic mentality, its particular intellectual bent. In all the fleeting centuries of history, in all the vicissitudes through which India has passed, a certain marked identity is visible. It has held passed a certain psychological traits which constitute its special heritage, and they will be the characteristic marks of the Indian people so long as they are privileged to have a separate existence. Individuality means independence of growth. It is not necessarily unlikeness, since man the world over is the same, especially so far as the aspects of spirit are concerned. The variations are traceable to distinctions in age, history and temperament. They add to the wealth of the world culture, since there is no royal road to philosophic development any more than to any other result worth having. Before we notice the characteristic features of Indian thought, a few words may be said about the influence of the West on Indian thought.

The question is frequently raised whether and to what extent Indian thought borrowed its ideas from foreign sources, such as Greece. Some of the views put forward by Indian thinkers resemble certain doctrines developed in Ancient Greece, so much that anybody interested in discrediting this

---------------

1 See I.A., 1918, p. 102. See also B.G., X. 32.

24

or that thought system can easily do so.1 The question of the affiliation of ideas is a useless pursuit. To an unbiassed mind, the coincidences will be an evidence of historical parallelism. Similar experiences engender in men’s minds similar views. There is no material evidence to prove any direct borrowings, at any rate by India, from the West. Our account of Indian thought will show that it is an independent venture of human mind. Philosophical problems are discussed without any influence from or relation to the West. In spite of occasional intercourse with the West, India had the freedom to develop its own ideal life, philosophy and religion. Whatever be the truth about the original home of the Aryans who came down to the peninsula, they soon lost touch with their kindred in the West or the North, and develop on the lines of their own. It is true that India was again and again invaded by armies pouring into it through the North-Western passes, but none of them, with the exception of Alexander’s, did anything to promote spiritual intercourse between the two worlds. Only latterly, when the gateway of the seas was opened, a more intimate intercourse has been fostered, the results of which we cannot forecast, since they are yet in the making. For all practical purposes, then, we may look upon Indian thought as a closed system or an autonomous growth.

II

GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF INDIAN THOUGHT

Philosophy in India is essentially spiritual. It is the intense spirituality of India, and not any great political

----------

1. Sir William Jones wrote: “Of the philosophical schools, it will be sufficient here to remark that the first Nyāya seems analogous to the Peripatetic ; the second, sometimes called Vaiśeṣika, to the Ionic ; the two Mīmāṁsās, of which the second is often distinguished by the name of Vedānta, to the Platonic ; the first Sāṁkhya to the Italic ; and the second of Patañjali to the Stoic philosophy ; so that Gautama corresponds with Aristotle, Kaṇāda with Thales, Jaimini with Socrates, Vyāsa with Plato, Kapila with Pythagoras, and Patañjali with Zeno” (Works, i, 360-1. See also Colebrooke, Miscellaneous Essays, i. 436 ff.) While the opinion that Greek. Thought has been influenced by the Indian is frequently held, it is not so often urged that Indian thought owes much to Greek speculation. (See Garbe, Philosophy of Ancient India, chap.ii.)

25

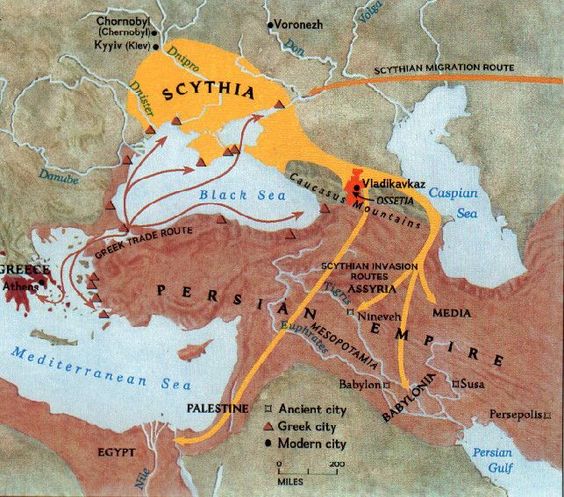

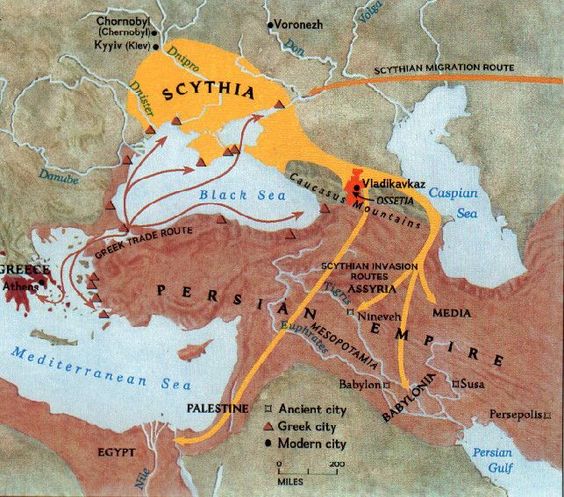

structure or social organization that it has developed, that has enabled it to resist the ravages of time and the accidents of history. External invasions and internal dissensions came very near crushing its civilization many times in its history. The Greek and the Scythian, the Persian and the Mogul, the French and the English have by turn attempted to suppress it, and yet it has its head held high. India has not been finally subdued, and its old flame of spirit is still burning. Throughout its life it has been living with one purpose. It has fought for truth and against error. It may have blundered, but it did what it felt able and called upon to do. The history of Indian thought illustrates the endless quest of the mind, ever old, ever new.

Scythian & Persian Empire, source: www.pinterest.com, access date: Feb.17, 2021

The founders of the philosophy strive for a socio-spiritual reformation of the country. When the Indian civilization is called a Brāhmanical one, it only means that its main character and dominating motives are shaped by its philosophical thinkers and religious minds, though these are not all of Brāhmin birth. The idea of Plato that philosophers must be the rulers and directors of society is practiced in India. The ultimate truths are truths of spirit, and in the light of them actual life has to be refined.

Religion in India is not dogmatic. It is a rational synthesis which goes on gathering into itself new conceptions as philosophy progresses. It is experimental and provisional in its nature, attempting to keep pace with the progress of thought. The common criticism that Indian thought,

26

by its emphasis on intellect, puts philosophy in the place of religion, brings out the rational character of religion in India. No religious movement has ever come into existence without developing as its support a philosophic content. Mr.Havell observes : “India, religion is hardly a dogma, but a working hypothesis of human conduct, adapted to different stages of spiritual development and different conditions of life.”1 Whenever it tended to crystallise itself in a fixed creed, there were set up spiritual revivals and philosophic reactions which threw beliefs into the crucible of criticism, vindicated the true and combated the false. Again and again, we shall observe, how when traditionally accepted beliefs become inadequate, nay false, on account of changed times, and the age grows out of patience with them, the insight of a new teacher, a Buddha or a Mahāvīra, Vyāsa or a Śaṁkara supervenes, stirring the depths of spiritual life. These are doubtless great moments in the history of Indian thought, times of inward testing and vision, when at the summons of the spirit’s breath, blowing where it listeth and coming whence no one knows, the soul of man makes a fresh start and goes forth on a new venture. It is the intimate relation between the truth of philosophy and the daily life of people that makes religion always alive and real.

Veda Vyāsa or Kṛṣṇa Dvaipāyana Vedavyāsa (कृष्णद्वैपायन वेदव्यास), source: www.patheos.com, access date: July 15, 2017.

1.

The problems of religion stimulate the philosophic spirit. The Indian mind has been traditionally exercised over the questions of the nature of Godhead, the end of life and the relation of the individual to the universal soul. Though philosophy in India has not as a rule completely freed itself from the fascinations of religious speculation, yet the philosophical discussions have been hampered by religious forms. The two were not confused. On account of the close connection between theory and practice, doctrine and life, a philosophy which could not stand the test of life, not in the pragmatistic but the larger sense of the term, had no chance of survival. To those who realise the true kinship between life and theory, philosophy becomes a way of life and theory, philosophy becomes a way of life, an approach to spiritual realisation. There has been no teaching, not even the Sāṁkhya01, which remained a mere -

----------

1 Aryan Rule in India, p. 170. See the article on The Heart of Hinduism: Hibbert Journal, October, 1922.

Notes

01. Sāmkhya (सांख्य): A school of philosophy emphasizing a dualism between Purusha and Prakrti, propounded by sage Kapila. The system of non-theistic philosophy is attributed to the sage Kapila (कपिल). It is called Sāṅkhya because it enumerates twenty-five Tattvas or various categories of reality beginning with Prakṛti or Pradhāna — primordial matter- and Puruṣa or Self. The conscious Self Puruṣa is passive and Prakṛti Active. Puruṣa becomes entangled in samsara and its attendant sufferings and is born again and again. A correct knowledge of the 25 categories will enable one to overcome ignorance and suffering and achieve liberation from samsāra. Source: www.wisdomlib.org, access date: Mar.9, 2025.

1.

2.

27

- word of mouth or dogma of schools. Every doctrine is turned into a passionate conviction, stirring the heart of man and quickening his breath.

It is untrue to say that philosophy in India never became self-conscious or critical. Even in its early stages rational reflection tended to correct religious belief. Witness the advance of religion implied in the progress from the hymns of the Veda to the Upaniṣads. When we come to Buddhism, the philosophic spirit has already become that confident attitude of mind which in intellectual matters bends to no outside authority and recognises no limit to its enterprise, unless it be as the result of logic, which probes all things, tests all things, and follows fearlessly wherever the argument leads. When we reach the several darśanas or systems of thought, we have mighty and persistent efforts at systematic thinking. How completely free from traditional religion and bias the systems are will be obvious from the fact that the Sāṁkhya is silent about the existence of God, though certain about its theoretical indemonstrability. Vaiśeṣika and Yoga, while they admit a supreme being, do not consider him to be the creator of the universe, and Jaimini refers to God only to deny his providence and moral government of the world. The early Buddhist systems are known to be indifferent to God, and we have also the materialist Cārvākas, who deny God, ridicule the priests, revile the Vedas and seek salvation in pleasure.

The supremacy of religion and of social tradition in life does not hamper the free pursuit of philosophy. It is a strange paradox, and yet nothing more than the obvious truth that while the social life of an individual is bound by the rigours of caste, he is free to roam in the matter of opinion. Reason freely questions and criticises the creeds in which men are born. That is why the heretic, the sceptic, the unbeliever, the rationalist and the freethinker, the materialist and the hedonist all flourish in the soil of India. The Mahābhārata says : “There is no muni who has not an opinion of his own.”

All this is evidence of the strong intellectuality of the Indian mind which seeks to know the inner truth and the law of all sides of human activity. This intellectual impulse -

Rishi Jaimini, Source: www.sanskritimagazine.com, access date: Mar.09, 2021.

Rishi Jaimini, Source: www.sanskritimagazine.com, access date: Mar.09, 2021.28

- is not confined to philosophy and theology, but extends over logic and grammar, rhetoric and language, medicine and astronomy, in fact all arts and sciences, from architecture to zoology. Everything useful to life or interesting to mind becomes an object of inquiry and criticism. It will give an idea of the all comprehensive character of intellectual life, to know that even such minutiæ as the breeding of horses and the training of elephants had their own śāstras and literature.

The philosophic attempt to determine the nature of reality may start either with the thinking self or the objects of thought. In India the interest of philosophy is in the self of man. Where the vision is turned outward the rush of fleeting events engages the mind. In India “Ātmānam viddhi,” know the self, sums up the law and the prophets. Within man is the spirit that is the centre of everything. Psychology and ethics are the basal sciences. The life of mind is depicted in all its mobile variety and subtle play of light and shade. Indian psychology realised the value of concentration and looked upon it as the means for the perception of the truth. It believed that there were no ranges of life or mind which could not be reached by a methodical training of will and knowledge. It recognised the close connexion of mind and body. The psychic experiences, such as telepathy and clairvoyance, were considered to be neither abnormal nor miraculous. They are not miraculous. They are not the products of diseased minds or inspiration from the gods, but powers which the human mind can exhibit under carefully ascertained conditions. The mind of man has the three aspects of subconscious, the conscious and the superconscious, and the “abnormal” psychic phenomena, called by the different names of ecstasy, genius, inspiration, madness, are the workings of the superconscious mind. The Yoga system of philosophy deals specially with these experiences, though the other systems refer to them and utilise them for their purposes.

The metaphysical schemes are based on the data of the psychological science. The criticism that Western metaphysics is one-sided, since its attention is confined to the waking state alone, is not without its force. There are other states of consciousness as much entitled to consideration as –

29

- the waking. Indian thought takes into account the modes of waking, dreaming and dreamless sleep. If we look upon the waking consciousness as the whole, then we get realistic, dualistic and pluralistic conceptions of metaphysics. Dream consciousness when exclusively studied leads us to subjectivist doctrines. The state of dreamless sleep inclines us to abstract and mystical theories. The whole truth must take all the modes of consciousness into account.

The dominance of interest in the subjective does not mean that in objective sciences India had nothing to say. If we refer to the actual achievements of India in the realm of positive science, we shall see that the opposite is the case. Ancient Indians laid the foundations of mathematical and mechanical knowledge. They measured the land, divided the year, mapped out the heavens, traced the course of the sun and the planets through the zodiacal belt, analysed the constitution of matter, and studied the nature of birds and beasts, plants and seed.1 “Whatever conclusions we may arrive at as to the original source of the first astronomical ideas current in the world, it is probable that to the Hindus is due the invention of algebra and its application to astronomy and geometry. From them also the Arabs received not only their first conceptions of algebraic analysis, but also those invaluable numerical symbols and decimal notation now current everywhere in Europe, which have rendered untold service to the progress of arithmetical science.”2 “The motions of the moon and the sun were carefully observed by the Hindus, and with such success that their determination of the moon’s synodical revolution is a much more correct on the Greeks ever achieved. They had a division of the ecliptic into twenty-seven and twenty-eight parts, suggested evidently by the moon’s period in days and –

--------------

1 We may quote a passage which is certainly not less that 2,000 years before the birth of Copernicus, from the Aitareya Brāhmaṇa : “The sun never sets nor rises. When people think to themselves the sun is setting, he only changes about after reaching the end of the day, and makes night below and day to what is on the other side. Then when people think he rises in the morning, he only shifts himself about after reaching the end of the night, and makes day below and night to what is on the other side. In fact he never does set at all. ” Haug’s Edition, iii. 44 ; Chān. Up., iii. II. 1-3. Even if this be folklore, it is interesting.

2 Monier Williams : Indian Wisdom, p. 184.

30

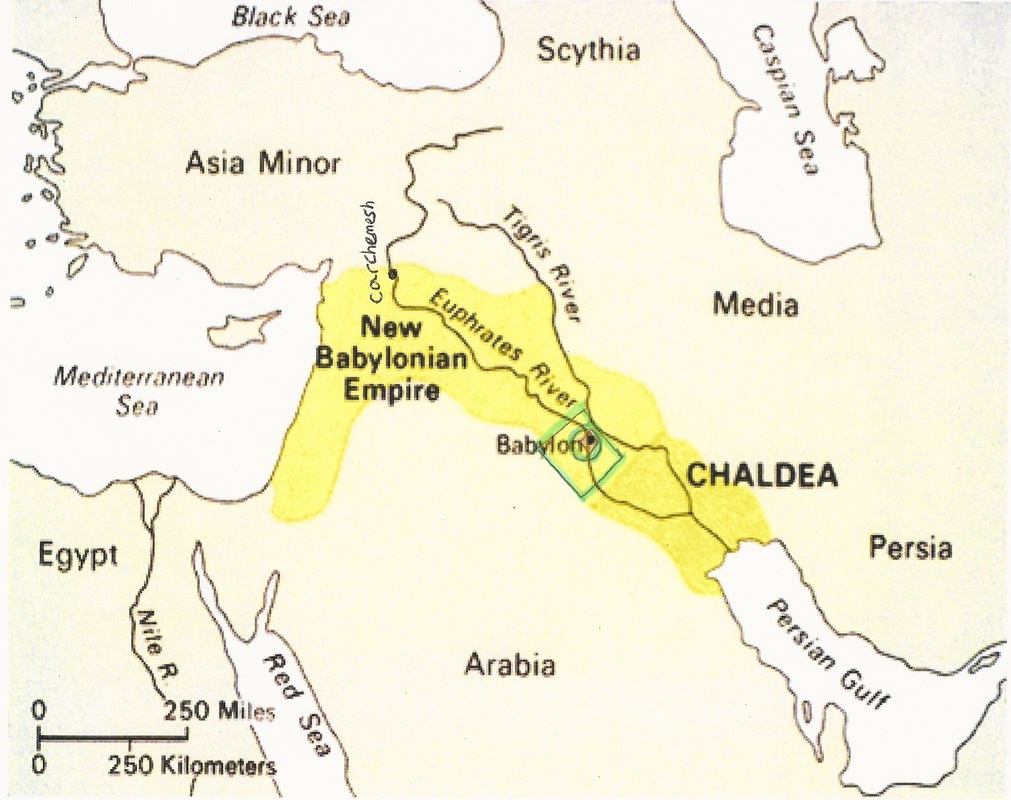

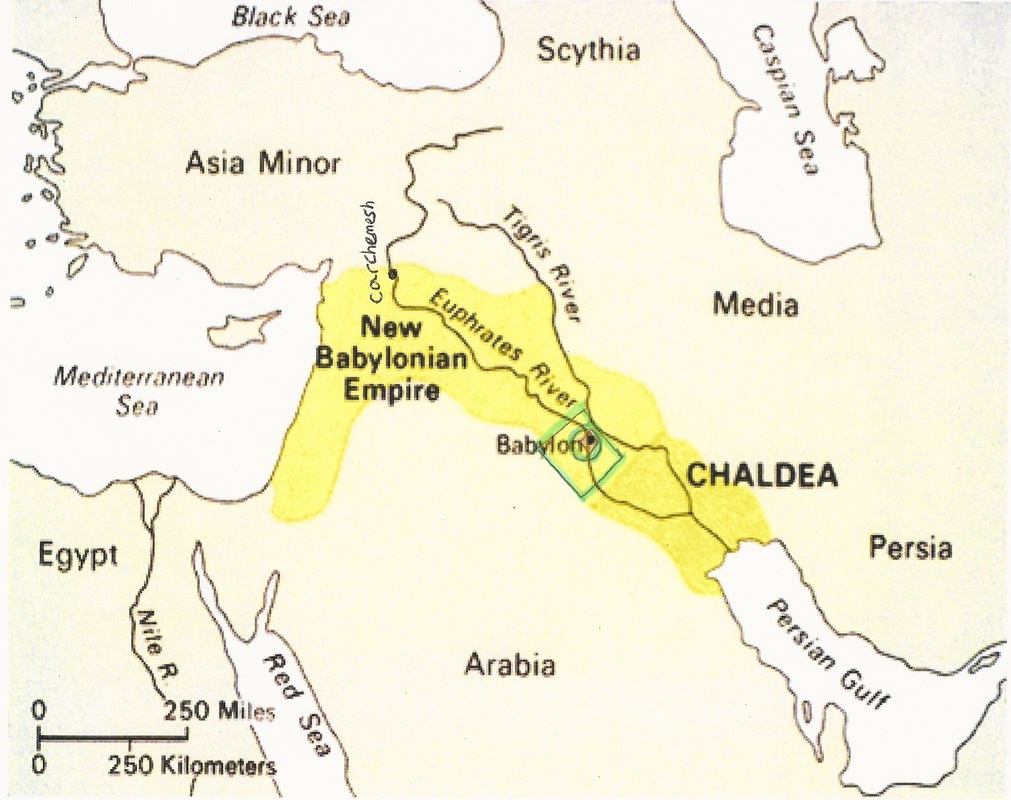

Location of ancient Chaldeans tribe lived and ruled Babylon, Source: chadeansapter.weebly.com, access date: March 18, 2021.

Location of ancient Chaldeans tribe lived and ruled Babylon, Source: chadeansapter.weebly.com, access date: March 18, 2021.

- seemingly their own. They were particularly conversant with the most splendid of the primary planets ; the period of Jupiter being introduced by them, in conjunction with those of the sun and the moon into the regulation of their calendar in the form of the cycle of sixty years, common to them and the Chaldeans.”1 It is now admitted that the Hindus at a very early time conceived and developed the two sciences of logic and grammar.2 Wilson writes : “In medicine, as in astronomy and metaphysics, the Hindus once kept pace with the most enlightened nations of the world ; and they attained as thorough a proficiency in medicine and surgery as any people whose acquisitions are recorded, and as indeed was practicable, before anatomy was made known to us by the discoveries of modern inquirers.”3 It is true that they did not invent any great mechanical appliances. For this a kind Heaven, which gave them the great watercourses and abundant supplies of food, is responsible. Let us also remember that these mechanical inventions belong, after all, to the sixteenth century and after, by which time India had lost her independence and become parasitic. The day she lost her freedom and began to flirt with other nations, a curse fell on her and she became petrified. Till then she could hold her own even in arts, crafts and industries, not to speak of mathematics, astronomy, chemistry, medicine, surgery, and those branches of physical knowledge practised in ancient times. She knew how to chisel stone, draw pictures, burnish gold and weave rich fabrics. She developed all arts, fine and industrial, which furnish the conditions of civilised existence. Her ships crossed the oceans and wealth brimmed over to Judæa, Egypt and Rome. Her conceptions of man and society, morals and religion were remarkable for the time. We cannot reasonably say that the Indian people revelled in poetry and mythology, and spurned science and philosophy, though it is true that they were more intent on seeking the unity of things than emphasising their sharpness and separation.

The speculative mind is more synthetic, while the scientific –

---------------

1 Colebrook’s translation of Bhāskara (भास्कर)’s Work of Algebra, p. xxii.

2 See Max Müller’s Sanskrit Literature,

3 Works, vol. iii. P. 269,

31

- one is more analytic, if such a distinction be permitted. The former tends to create cosmic philosophies which embrace in one comprehensive vision the origin of all things, the history of ages and the dissolution and decay of the world. The latter is inclined to linger over the dull particulars of the world and miss the sense of oneness and wholeness. Indian thought attempts vast, impersonal views of existence, and makes it easy for the critic to bring the charge of being more idealistic and contemplative, producing dreamy visionaries and strangers in the world, while Western thought is more particularist and pragmatistic. The latter depends on what we call the senses, the former presses the soul sense into the service of speculation. Once again it is the natural conditions of India that account for the contemplative turn of the world and express his wealth of soul in song and story, music and dance, rites and religious, undisturbed by the passions of the outer world. “The brooding East,” frequently employed as a tern of ridicule, is not altogether without its truth.

It is the synthetic vision of Indian that has made philosophy comprehend several sciences which have become differentiated in modern times. In the West during the last hundred years or so several branches of knowledge till then included under philosophy, economics, politics, morals, psychology, education have been one by one sheared away from it. Philosophy in the time of Plato meant all those sciences which are bound up with human nature and the core of man’s speculative interests. In the same way in ancient Indian scriptures we possess the full content of the philosophic sphere. Latterly in the West philosophy became synonymous with metaphysics, or the abstruse discussions of knowledge, being and value, and the complaint is heard that metaphysics has become absolutely theoretical, being cut off from the imaginative and the practical sides of human nature.

If we put the subjective interest of the Indian mind along with its tendency to arrive at a synthetic vision, we shall see how monistic idealism becomes the truth of things. To it the whole growth of Vedic thought points ; on it are based the Buddhistic and the Brāhmanical religious ; it is –

32

- the highest truth revealed to India. Even systems which announce themselves as dualistic or pluralistic seem to be permeated by a strong monistic character. If we can abstract from the variety of opinion and observe the general spirit of Indian thought, we shall find that it has a disposition to interpret life and nature in the way of monistic idealism, though this tendency is so plastic, living and manifold that it takes many forms and expresses itself in even mutually hostile teachings. We may briefly indicate the main forms which monistic idealism has assumed in Indian thought, leaving aside detailed developments and critical estimates. This will enable us to grasp the nature and function of philosophy as understood in India. For our purposes monistic idealism is of four types : (1) Non-dualism or Advaitism ; (2) Pure monism ; (3) Modified monism ; and (4) Implicit monism.

From Left to Right: Elephanta ancient Buddhist cave, Mumbai, Mahārāṣṭra (महाराष्ट्र), Bhārat (भारत). UNESCO World Heritage site, around the 2nd century BCE., Source: Facebook, page"Ancient History of India," access date: April 17, 2021, and this picture I took in Elephanta Cave on November 7, 2024.

The activities of the self are assigned to the three states of waking, dreaming and dreamless sleep. In dream states an actual concrete world is presented to us. We do not call that world real, since on waking we find that the dream world does not fit in with the waking world ; yet relatively to the dream state the dream world is real. It is discrepancy from our conventional standards of waking life, and not any absolute knowledge of truth as subsisting by itself, that tells us that dream states are less real than the waking ones. Even waking reality is a relative one. It has no permanent existence, being only a correlate of the waking state. It disappears in dream and sleep. The waking consciousness and the world disclosed to it are related to each other, depend on each other as the dream consciousness and the dream-

33

-world are. They are not absolutely real, for in the words of Śaṁkara, while the “dream-world is daily sublated, the waking world is sublated under exceptional circumstances.” In dreamless sleep we have a cessation of the empirical consciousness. Some Indian thinkers are of opinion that we have in this condition an objectless consciousness. At any rate this is clear, that dreamless sleep is not a complete non-being or negation for such a hypothesis conflicts with the later recollection of the happy repose of sleep. We cannot help conceding that the self continues to exist, though it is bereft of all experience. There is no object felt and there can be none so long as the sleep is sound. The pure self seems to be unaffected by the flotsam and jetsam of ideas which rise and vanish with particular moods. “What varies not, nor changes in the midst of things that vary and change is different from them.”1 The self which persists unchanged and is one throughout all the changes is different from them all. The conditions change, not the self. “In all the endless months, years and small and great cycles, past and to come, this self-luminous consciousness alone neither rises nor ever sets.”2 An unconditioned reality where time and space along with all their objects vanish is felt to be real. It is the self which is the unaffected spectator of the whole drama of ideas related to the changing moods of waking, dreaming and sleeping. We are convinced that there is something in us beyond joy and misery, virtue and vice, good and bad. The self “never dies, is never born-unborn, eternal, everlasting, this ancient one can never be destroyed with the destruction of the body. If the slayer thinks he can slay, or if the slain thinks he is slain, they both do not know the truth, for the self neither slays nor is slain.”3

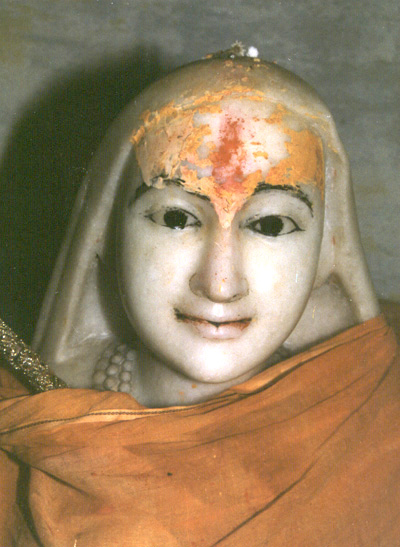

Murti of Śaṁkara at his Samadhi Mandir, behind Kedarnath Temple (केदारनाथ मंदिर - Kēdāranātha Mandira - Temple of the God of the field), in Kedarnath, Bhārat, source: en.wikipedia.org, access date: Mar.30, 2025.

1.

In addition to the ever-identical self, we have also the empirical variety of objects. The former is permanent, immutable, the latter impermanent and ever changing. The former is absolute, being independent of all objects. The latter changes with the moods.

---------------

1 “Yeṣu vyāvartamāneṣu yad anuvartate tat tebhyo bhinnam” (Bhāmatī).

2 Pañcadaśī, i. 7.

3 Kaṭha Up, ii. 18-19; B.G., ii. 19-20.

34

How are we to account for the world? The empirical variety is there bound in space, time and cause. If the self is the one, the universal, the immutable, we find in the world a mass of particulars with opposed characters. We can only call it the not-self, the object of a subject. In no case is it real. The principal categories of the world of experience, time, space and cause are self-contradictory. They have no real existence. Yet they are not non-existent. The world is there, and we work in it and through it. We do not and cannot know the why of this world. It is this fact of its inexplicable existence that is signified by the word māyā. To ask what is the relation between the absolute self and the empirical flux, to ask why and how it happens, that there are two, is to assume that everything has a why and a how. To say that the infinite becomes the finite or manifest itself as finite is on view utter nonsense. The limited cannot express or manifest the unlimited. The moment the unlimited manifest itself in the unlimited, it itself becomes limited. To say that the absolute degenerates or lapses into the empirical is to contradict its absoluteness. No lapse can come to a perfect being. No darkness can dwell in perfect light. We cannot admit that the supreme, which is changeless, becomes limited by changing. To change is to desire or to feel a want, and it shows lack of perfection. The absolute can never become an object of knowledge, for what is known is finite and relative. Our limited mind cannot go beyond the bounds of time, space and cause, nor can we explain these, since every attempt to explain them assumes them. Through thought, which is itself a part of the relative world, we cannot know the absolute self. Our relative experience is a waking dream. Science and logic are parts of it and products of it too. This failure of metaphysics is neither to be wept over nor to be laughed over, neither to be praised not blamed, but understood. With a touching humility born of intellectual strength, a Plato, or a Nāgārjuna, a Kant or a Śaṁkara, declares that our thought deals with the relative, and has nothing to do with the absolute.

Though the absolute being is not known in the logical way, it is yet realised by all who strain to know the truth, as-

35

-the reality in which we lie, move and have our being. Only through it can anything else be known. It is the eternal witness of all knowledge. The non-dualist contends that his theory is based on the logic of facts. The self is the inmost and deepest reality, felt by all, since it is the self of all things known and unknown too, and there is no knower to know it except itself. It is the true and the eternal, and there is nought beside it. As for the empirical ramifications which also exist, the non-dualist says, well they are there, and there is and end of it. We do not know and cannot know why. It is all a contradiction, and yet is actual. Such is the philosophical position of Advaita or non-dualism taken up by Gauḍapāda and Śaṁkara.

Guru Gauḍapāda Acharya, Source: vanamalaarts.org, access date: Apr.25, 2021.

There are Advaitins who are dissatisfied with this view, and feel that it is no good covering up our confusion by the use of the word māyā. They attempt to give a more positive account of the relation between the perfect being absolutely devoid of any negativity, the immutable real, felt in the depths of experience and the world of change and becoming. To preserve the perfection of the one reality we are obliged to say that the world of becoming is not due to an addition of any element from outside, since there is nothing outside. It can only be by a diminution. Something negative like Plato’s non-being or Aristotle’s matter is assumed to account for change. Through the exercise of this negative principle, the immutable seems to be spread out in the moving many. Rays stream out of the sun which nevertheless did not contain them. Māyā is the name of the negative principle which lets loose the universal becoming, thereby creating endless agitation and perpetual disquiet. The flux of the universe is brought about by the apparent degradation of the immutable. The real represents all that is positive in becoming. The things of the world ever struggle to recover their reality, to fill up what is lacking in them, to shake off their individuality and separateness, but are prevented from doing so by their inner void, the negative māyā constituted by the interval between what they are and what they ought to be. If we get rid of māyā, suppress the tendency to duality, abolish the interval, fill up the deficit, and allow the disturbance to relax, space, time and change reach back into –

36

- pure being. As long as the original insufficiency of māyā prevails, things are condemned to be existent in space-time-cause world. Māyā is not a human construction. It is prior to our intellect and independent of it. It is verily the generator of things and intellects, the immense potentiality of the whole world. It is sometimes called the prakṛti. The alternations of generation and decay, the ever-repeated cosmic evolutions, all represent this fundamental deficit in which the world consists. The world of becoming is the interruption of being. Māyā is the reflection of reality. The world-process is not so much a translation of immutable being as its inversion. Yet the world of māyā cannot exist apart from pure being. There can be no movement, if there were not immutability, since movement is only a degradation of the immutable. The truth of the universal mobility is the immobile being.

As being is a lapse from being, so is avidyā or ignorance a fall from vidyā or knowledge. To know the truth, to apprehend reality, we have to get rid of avidyā and its intellectual moulds, which all crack the moment we try to force reality into them. This is no excuse for indolence of thought. Philosophy as logic on this view persuades us to give up the employment of the intellectual concepts which are relative to our practical needs and the world of becoming. Philosophy tells us that, so long as we are bound by intellect and are lost in the world of many, we shall seek in vain to get back to the simplicity of the one. If we ask the reason why there is avidyā, or māyā, bringing about a fall from vidyā or from being, the question cannot be answered. Philosophy as logic has here the negative function of exposing the inadequacy of all intellectual categories, pointing out how the objects of the world are relative to mind that thinks them and possess no independent existence. It cannot tell us anything definite about either the immutable said to exist apart from what is happening in the world, or about māyā, credited with the production of the world. It cannot help us directly to the attainment of reality. It, on the other hand, tells us that to measure reality we have to distort it. It may perhaps serve the interests of truth when once it is independently ascertained. We can think it out,

37

defend it logically and help its propagation. The supporters of pure monism recognise a higher power than abstract intellect which enables us to feel the push of reality. We have to sink ourselves in the universal consciousness and make ourselves co-extensive with all that is. We do not then so much think reality as live it, do not so much know it as become it. Such an extreme monism, with its distinctions of logic and intuition, reality and the world of existence, we meet with in some Upaniṣads, Nāgārjuna and Śaṁkara in his ultra-philosophical moods, Śrī Harṣa and the Advaita Vedāntins, and echoes of it are heard in Parmenides and Plato, Spinoza and Plotinus, Bradley and Bergson, not to speak of the mystics, in the West.1

Whatever the being, pure and simple, may be to intuition, to intellect it is nothing more or less than an absolute abstraction. It is supposed to continue when every fact and form of existence is abolished. It is residue left behind when abstraction is made from the whole world. It is a difficult exercise set to the thought of man to think away the sea and the earth, the sum and the stars, space and time, man and God. When an effort is made to abolish the whole universe, sublate all existence, nothing seems to remain for thought. Thought, finite and relational, finds to its utter despair that there is just nothing at all when everything existent is abolished. To the conceptual mind the central proposition of intuition, “Being only is,” means that there is just nothing at all. Thought, as Hegel said, can only work with determinate realities, concrete things. To it all affirmation implies negation, and vice versa. Every concrete is a becoming, combining being and non-being, positive and negative. So those who are not satisfied with the intuited being, and wish to have a synthesis capable of being attained by thought which has a natural instinct for the concrete, are attracted to a system of objective idealism. The concrete idealists try to put together the two concepts of pure being

-----------

1 In the Sāṁkhya philosophy we have practically the same account of the world of experience, which does not in the least stain the purity of the witness self. Only a pluralistic prejudice which has no logical basis asserts itself, and we have a plurality of souls. When the pluralism collapses, as it does at the first touch of logic, the Sāṁkhya theory becomes identical with the pure monism here sketched.

38

and apparent becoming in the single synthesis of God. Even extreme monists recognise that becoming depends on being, though not vice versa. We get now a sort of refracted absolute, a God who has in Him the possibility of the world, combines in His nature the essence of all being, as well as of becoming, unity as well as plurality, unlimitedness and limitation. The pure being now becomes the subject, transforming itself into object and taking back the subject, transforming itself. Position, opposition, and composition, to use Hegelian expressions, go on in an eternal circular process. Hegel rightly perceives that the conditions of a concrete world are a subject and an object. These two opposites are combined in every concrete. The great God Himself has in Him the two antagonistic characters where the one is not only through the other, but is actually the other. When such a dynamic God eternally bound in the rotating wheel is asserted, all the degrees of existence, from the divine perfection up to vile dust, are automatically realised. The affirmation of God is the simultaneous affirmation of all degrees of reality between it and nothing. We have now the universe of thought constructed by thought, answering to thought and sustained by thought, in which subject and object are absorbed as moments. The relations of space, time and cause are not subjective forms, but universal principles of thought. If on the view of pure monism we cannot understand the exact relation between identity and difference, we are here on better ground. The world is identity gone into difference. Neither is isolated from the other. God is the inner ground, the basis of identity ; the world is the outer manifestation, the externalisation of self-consciousness.

Such a God, according to the theory of pure monism, is just the lapse from the absolute, with the least conceivable interval separating him from pure being or the absolute. It is the product of avidyā by the least conceivable extent. In other words, this concrete God is the highest product of our highest intelligence. The pity is, that it is a product after all, and our intelligence, however near it approximates to vidyā, is not yet vidyā. This God has in him the maximum of being and the minimum

39

of defect-still a defect. The first touch of māyā, the slightest diminution of absolute being, is enough to throw it into space and time, though this space and this time will be as near as possible to the absolute unextendedness and eternity. The absolute one is converted into the Creator God existent in some space, moving all things from within without stirring from His place. God is the absolute objectivised as something somewhere, a spirit that pushes itself into everything. He is being-none-being, Brahman-māyā, subject-object, eternal force, the motionless mover of Aristotle, the absolute spirit of Hegel, the (absolute-relative) viśiṣṭādvaita of Rāmānuja, the efficient as well as the final cause of the energising of God could not have begun and could never come to an end. It is its essential nature to be ever at unrest.

Sri Ramanujacharya, pioneer of Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedanta and the foremost Jeeyar of Sri Vaishnava Sampradaya, Source: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ramanuja, access date: May 06, 2017.

Sri Ramanujacharya, pioneer of Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedanta and the foremost Jeeyar of Sri Vaishnava Sampradaya, Source: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ramanuja, access date: May 06, 2017.

40

it is difficult to defend the position. Admitting that the conceptual plan of reality revealed to thought is true, still, it is sometimes urged, thought is not identical with reality. By compressing all concepts into one, we do not go beyond concepts. A relation is only a part of the mind that relates. Even an infinitely superior mind is yet a mind and of the same mould as man’s. The theory of modified monism is adopted by some Upaniṣads, and the Bhagavadgītā, some followers of Buddhism and Rāmānuja, if not Bādarāyaṇa. In the West Aristotle and Hegel stand out as witnesses to it.

According to the first view perfect being is real ; unreal becoming is actual, though, we do not know why. According to the second, the world becoming is a precipitation (apparent) of pure being into space and time by the force of diminution or māyā. According to the third, the highest product we have is a synthesis of pure being and not-being in God. We are immediately under a logical necessity to affirm all intermediate degrees of reality. If pure being is dismissed as a concept useless so far as the world of experience is concerned and we also disregard as illogical the idea of a Creator God, then what exists is nothing more than a mere flux of becoming, ever aspiring to be something else than what it is. The main principle of Buddhism results. In the world of existence, on the hypothesis of modified monism, the specific characters of the degrees of intermediate reality are to be measured by the distance separating them from the integral reality. The common characters of all of them are existence in space and time. Closer attention reveals to use more and more special attributes. Admit the distinction between thinking reals and unthinking objects, and we have the dualistic philosophy of Madhva. Even this is fundamentally

Śri Madhvācārya (A.D.1238-1317), Source: goloka.com, access date: May 11, 2021

a monism so long as the reals are dependent (paratantra) on God, who alone is independent (svatantra). Emphasise the independence of the thinking beings, and we have pluralism according to Sāṃkhya, if only we do not worry about the existence of God which cannot be demonstrated. Add to it the plurality of the objects of the world, we have pluralistic realism, where even God becomes one real, however great or powerful, among others. In the discussions about

41

the intermediate degrees of reality the unit of individuality seems to depend upon the fancy of the philosopher. And whether a system turns out atheistic or theistic is determined by the attention paid to the absolute under the ægis of which the drama of the universe is enacted. It sometimes shines out brilliantly with its light focussed in a God and at other times fades out. These are the different ways in which the mind of man reacts to the problems of the world according to its own peculiar constitution.

There is a cordial harmony between God and man in Indian thought, while the opposition between the two is more marked in the West. The mythologies of the peoples also indicate it. The myth of Prometheus, the representative man, who tries to help mankind by defending them against Zeus who desires to destroy the human race and supplant them with a new and better species, the story of the labours of Hercules who tries to redeem the world, the conception of Christ as the Son of Man, indicate that man is the centre of attention in the West. It is true that Christ is also called the Son of God, the eldest begotten who is to be sacrificed before a just God’s anger can be appeased. Our point here is that the main tendency of Western culture is an opposition between man and God, where man resists the might of God, steals fire from him in the interests of humanity. In India man is a product of God. The whole world is due to the sacrifice of God. The Puruṣa Sūkta speaks of such an eternal sacrifice which sustain man and the world.1 In it the whole world is pictured as one single being of incomparable vastness and immensity, animated by one spirit, including within its substance all forms of life.

Hercules, developed on Apr.29, 2025

The dominant character of the Indian mind which has coloured all its culture and moulded all its thoughts is the spiritual tendency. Spiritual experience is the foundation of India’s rich cultural history. It is mysticism, not in the sense of involving the exercise of any mysterious power, but only as insisting on a discipline of human nature, leading to realisation of spiritual. While the sacred scriptures of the Hebrews and the Christians are more religious and ethical, those of the Hindus are more spiritual and

-------------

1 R.V., x. 90 ; see also RV., x. 81, 3 ; Śvetāśvatara Up., iii. 3 ; B.G., xi.

42

contemplative. The one fact of life in India is the Eternal Being of God.

1.

2.

3.