In my opinion, studying other cultures should form a part of the general education provided in schools. And the first thing that should be taught is that, in a planetary situation, dialogue between cultures is asymmetrical; it takes place in a Western medium, using a Western language, and in fact, the very concept of intercultural dialogue sounds suspiciously Euro-American. In a certain sense, the rest of the world has no choice but to undergo what is known as westernization or modernization (on the ideological, technological, economic, and political levels) as ambiguous and in need of qualification as these concepts.

4

might arguably be. To palliate the effects of ravaging globalization, a good antinode is precisely the learning and understanding of the "Others." This book seeks to foster and expand this understanding. At the same time, the journey toward modernity means that each culture will have to rediscover and reinterpret its own identity.

The exciting thing is that for Jainism, this is not new. The whole of its history, as in the case of any other tradition, has to be seen in the context of continual dialogue with the Other, about which it defines itself, it struggles, it opposes, it is stimulated, and it reconsiders. Let us take a look.

Jainism is an ancient religion, with at least 2,500 or 3,000 years of more or less recorded history and infinite eons of another history, nowadays usually termed "mythical." Initially, the members of this community were known as "bondless ones" (nirgranthas), a label that reflects the ascetic nature of this religion. Its historical and mythical leaders were called by the strange name of "ford makers" (tīrthaṅkaras). Ford? Yes, crossing places in rivers would enable others to cross over to the farther shore of liberation (nirvāṇa). A synonym for tīrthaṅkara is the word jina, which means “victorious” or “spiritual victor” (Monier-Williams 1899: 421). The tīrthaṅkara or jina is someone who vanquishes his passions, rids himself of attachment, who attains enlightenment, and preaches the Jain path by which others could reach the further shore of salvation. The last of these perfect guides was Mahāvīra (6th-5th centuries BC), the jina of our times. Jainism is, as its name suggests, the religion these jinas gave to the world. All followers of this path marked out by the jinas are known as jainas or Jains.

At the origin, the Others about which Jainism began to define itself were Vedic Brāhmaṇism and a series of religious groups referred to as Śramaṇic, the foremost of these being Buddhism and, in fact, the group to which Jainism itself pertained. For many centuries, Buddhism constituted this Other, at one and the identical time sister and rival, a religion with which Jainism both struggled and learned and fed. Later, the Other took the form of devotional Hinduism, especially the Śaiva and Vaiṣṇava persuasions. Then came Islamic India. In the 19th and 20th centuries, there was the British Raj. Today, Jainism has to respond to modernity and Hindu nationalism. In all cases, Jainism has had to transform itself and create a new discourse. This long history of interaction is another thing I want to clarify in this book. Jainism is not a sacred monolith but rather a tradition that has transformed itself in response to its journey to the new; Jainism – and Indian traditions as a whole – possess more resources and capacity for adaptation than we think.

For decades observers have had the impression that Jainism had reached the fag end of its history; it was an unchanging tradition with no real developments (von Glasenapp 1925: 163-165), which remained utterly conservative. I hope to show, however, that although the tradition has placed particular emphasis on

5

faithfulness to its principles, it was not and is not as static as it is made out to be. Therefore, I believe that the historical approach I have partially adopted and the incursions into other ways of understanding the religion in other Indian traditions are relevant. From this point of view, one understands that all traditions are dynamic phenomena, in perpetual motion and contact with the Others. Only thus can we realize the value of the immense role played by Jainism in the construction of Indian civilization, I believe that the study and popularisation of South Asian history have placed too much emphasis on Brāhmaṇic, Vedic, and Sanskrit elements, to the detriment of other equally key factors – Buddhist, Jain, Tantric, Hindu devotional, Tribal, Muslim, Sikh, and Christian. This work seeks to restore Jainism's proper place in constructing Indian civilization. Let us look at an example.

The present-day Jain community is not significant. It numbers about 4.5 or 5 million practicing faithful and has remained within the confines of the country of its birth, India, with just small enclaves of Indian Jains in Africa, Europe, America, and other points of Asia. However, in former times, it was a religion with numerous followers, especially between the 5th and 12th centuries, when it successfully rivaled the other Indian traditions. Its influence on the values and practices of Hindus and Buddhists was considerable. Jainism has, for example, been the religion that puts the most significant emphasis on such issues as vegetarianism or non-violence (ahiṃsā), which are today the heritage of millions of Indians and the Indic religions. The doctrine of ahiṃsā gained such prestige that Brāhmaṇism raised it to the status of the cardinal virtue. Its entire system of worship based on the sacrifice of animals stipulated in the holy scriptures. Had to be drastically revised. It is not surprising that the two greatest monarchs of India, the Buddhist Aśoka (3rd century BC) and the Muslim Akbar (16th-17th century), were visible proponents of the doctrine of non-violence. Today, Hindu devotional worship (pūjā) is invariably vegetarian, and the slaughter of animals has been prohibited in many states of India. Thanks to Gandhi’s message, the ethics, and praxis of non-violence have reached every corner of the planet.

The above will challenge the widespread cliché – well dissected by John Cort (1998: 3) – that the Jain religion is like the poor and more or less insignificant relation of Hinduism or Buddhism.

Indeed, let's examine the treatises on South Asian spirituality. Jainism appears – invariably in the shadow of Buddhism – when the wave of spiritual unrest afflicting northern India in the 8th-4th centuries BC is considered. The treatises speak of the intellectual and social changes of this crucial time and of the new traditions of renunciants-of-the-world (Śramaṇas) led by charismatic leaders like the Buddha and Mahāvīra. Then, from this point onward, the Jain religion disappears from the treatises. Jainism is identified only with its most ancient formulation and its weight is recognized only as the challenge it represented for the Vedic and Buddhist traditions, some centuries before the Common Era. Authors like Kundakunda (2nd century), Umāsvāti (3rd-4th cen-

6

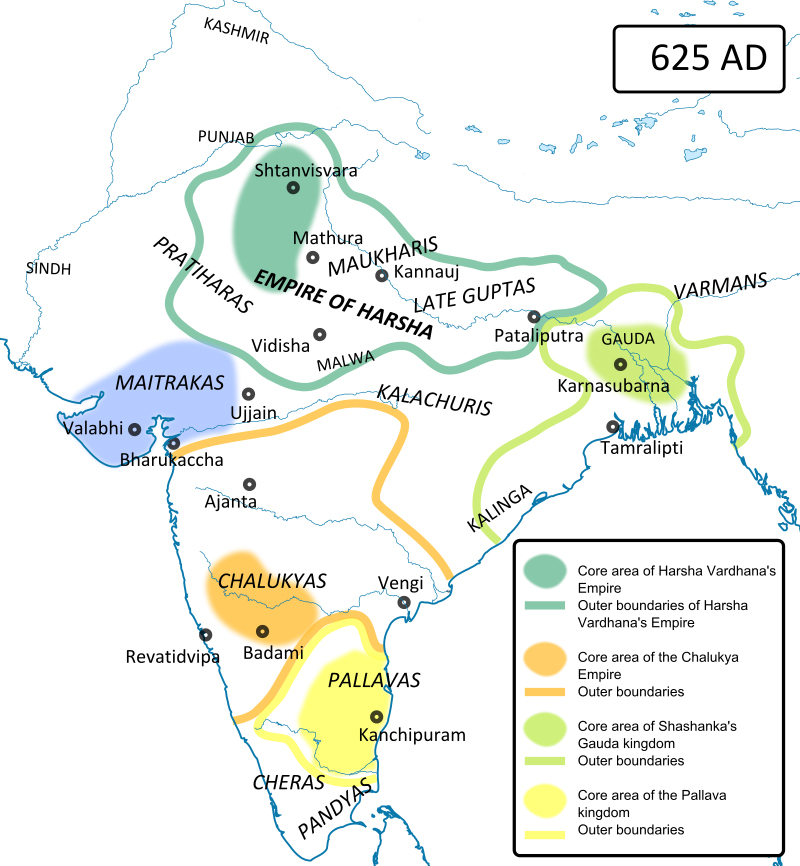

turies), Haribhadra (8th century), Jinasena (9th century), or Hemacandra (12th century), whose genius had a tremendous impact on Indian philosophy and spirituality, are not even mentioned. Similarly neglected is the influence Jainism had on the Gaṅga, Rāṣṭrakūṭa, Hoysala, or Solaṅkī dynasties in the post-Gupta period (middle ages). Scarcely studied, too, are the practices of worship in the temples or the ideals and practices of the lay community – not to mention the enormous impact that Jainism had on the development of the vernacular languages: Tamil, Kannada, Marathi, Hindi or Gujarati. Yet another aspect scarcely mentioned is the powerful influence that Jainism had on Indian literature and art. Moreover, the general tone of many Western scholars borders on scornful. Jainism is presented as marginal, as being of little or no consequence for modern society; alternatively, it is depicted as a washed-out, atheist, and irrelevant sect (Hopkins 1898: 296). At best, the only interest Jainism is seen to hold is in its having preserved an archaic, pre-philosophical, and pessimistic vision of the world.

The Later Guptas as vassals of Harsha C.625 CE., Source: en.wikipedia.org, Access date: May 09, 2023.

The Later Guptas as vassals of Harsha C.625 CE., Source: en.wikipedia.org, Access date: May 09, 2023.

INDOLOGISTS VERSUS SOCIOLOGISTS

Obviously, real experts know the importance of this tradition. There is a long tradition of Jain studies.

The pioneers were European missionaries and army officers like Thomas Colebrooke, Horace Wilson, Otto Böthlingk, and Father J. Stevenson. He translated the first Jain texts into European languages in the first half of the 19th century. At the end of that century came the first severe studies by Indologists and Sanskritists of the stature of Albrecht Weber, George Bühler, and Hermann Jacobi. In the 20th century, another generation of scholars, like Walther Schubring and Ludwig Alsdorf, contributed to enriching our knowledge. The general introduction by Helmuth von Glasenapp, Der Jainismus, published in 1925, represented an essential advance in disseminating this tradition for the intelligent lay reader. Of course, I am referring to the works of Western authors writing for a Western audience. I do not include here the numerous studies by the Jains themselves, so liberally drawn upon by the Indologists.

The next milestone in disseminating knowledge of Jainism was the superb introduction by Padmanabh Jaini, The Jaina Path of Purification, published in 1979. But the problem with Jainology is that its works tend only to be known by scholars and are not so accessible to the less specialized reader. And there is yet another problem.

Most studies of religions tend to concentrate on the spiritual virtuosos and their path (monks and nuns, renunciants, saints, and prophets) while tending to forget or dismiss the spirituality of the great majority. Jainism is no exception to this. One only needs to leaf through most of the authors mentioned above to see they have concentrated on Jainism’s written tradition, transmitted by ascetic.

7

monks whose work is based on the concerns and characteristics of the monastic community. As a result, Indologists have bequeathed us a relatively arid, androcentric, and ascetic picture of Jainism. With few exceptions, the vision that is offered is excessively concentrated on textual study or on historical details. Significantly, there are many more treatises that deal with the ancient history of the Jains than with the living Jainism of today. The experts have bequeathed the unfortunate cliché that only ancient India has anything to teach us.

Although the viewpoints of the Indologists and Sanskritists are of fundamental importance in understanding the Jains, they, more than any others, have encouraged the classical stereotypes attributed to the community: that of their excessive sobriety, austerity, and tendency to go in for ordeals. Without denying the importance that asceticism has for members of the community, all those of us who have lived with members of this community will agree with me – and John Cort (1991:213) – in that Jains are no less lively than ever-extrovert Hindus, nor are their rituals less eye-catching or sensual even, than those of their neighbors. There is a yawning gulf between the monastic view of Jainism and the living religion practiced by the lay people. The same can be said about Hinduism in general, and hence the great disillusionment of enthusiasts when they have read or studied (Said 1978: 122-123).

I think that the language of historians and Indologists has to be complemented by that of sociologists and anthropologists, who can offer us a more up-to-date picture of the tradition. Textual study is essential to get to know the religious thought of a people, but this is insufficient for determining their religious behavior. Precisely by putting somewhat less emphasis on textual study and combining it with field work, new writers have emerged like Ken Folkert, John Cort, Paul Dundas, Caroline Humphreys, James Laidlaw, Christopher Chapple and Lawrence Babb, who have provided a richer and livelier view of Jainism. I believe that is important to make available anthropological information that explains the tradition as lived by the great majority of its adherents. The Jainism of lay people, let us state this once and for all, is not an inferior, dilute or popular version of a true or authentic Jainism practised by the monks and nuns (we could say the same of Buddhism). Lay Jainism is an integral way of life, and is a path for spiritual progress which follows the same lines, in the same direction, as those of their virtuoso ascetic counterparts. However, they integrate the values, aims and traditional metaphysics in a different way.

Although as a general rule I shall maintain the impersonal voice of the Indologists (not because of any presumed objectivity but as a way of recognizing my appropriation of the ideas and evaluations of the experts, and I am equality indebted to the work of the ideas and evaluations of the experts) sociologists, this work is based also in my direct experience with different Jain groups in Delhi, Rajasthan, Gujarat, Maharashtra and Karnataka.

8

WHAT JAINISM CAN TEACH US

Intercultural dialogue should not lead to a mutual comprehension out of mere courtesy. I think that readers have to have the sagacity to learn from and draw on humanity’s traditions of wisdom. That is the next of the purposes implicit in this work. That is, the traditions wisdom. That is the next of the purposes implicit in this work. That is, the traditions of India should not just be made known to a wider audience just because they are practised by millions of people, or that they represent the world view of millions of people, or because the world has shrunk, but because they have something to contribute to any corner of the world. Jainism can teach us.

Asia would not be what it is without the great Jain contribution of non-violence (ahiṃsā), channelled marvellously by Buddhism: the virtue of not harming any living being, or more exactly, the righteous state of mind ever mindful not to inflict harm on any such creature nor on one self. Ahiṃsā is the fundamental feature that would characterise the Jain community as a whole and Jainism as a religion. This ethic has inspired all sections of the community for centuries and has served to carry the classic forms of Jainism down to the present. The virtue of ahiṃsā is the epicentre of what could be a Jain way of life. And the world would do well to put this virtue in pre-eminent position, and adopt a more Jain-like vision of our environment, human relations and the beings around us. Jain teaching on non-violence constitutes one of the most powerful and committed solutions to the problem of violence in the world.

From the Indian perspective, all of us take part in the same flow of life (saṃsāra). Nature and society are not in opposition. At the same time, India has to take on the challenge of modernization. And modernism invariably brings with its consumerism, aggressive capitalist viewpoints, the exploitation of the environment, the use of invasive technology, and so on. The future, from a global point of view (an overall anthropological, cultural, environmental, psychological and sociological point of view) is not looking good. Nonetheless, India has its own resources for dealing with these problems. And one of these, although obviously not the only one, resides in the country’s renunciant traditions. For many centuries, the renunciants of India (Buddhists, Jains, Śaivas) have preached silently, by example, the virtues of frugality, non-attachment, non-violence and non-consumerism. There are many ways to adapt and reinterpret the ethics and spiritual values of Jainism to help to palliate modern social and environmental ills. A more compassionate attitude to animals, ethically – if not necessarily in dietary terms – more vegetarian, with less attachment to possessions, could bring about much good for society.

Jainism, at the same time, promotes the doctrine of non-absolutism (anekāntavāda) a concept that could be translated as philosophical pluralism. A reconciliatory pluralism that seeks to avoid all extremes. I believe that an acute perspectivism such as we find in Jainism could help to bring about a world, an existence, that is healthier, more understanding and more intelligent.

9

And it could be a good antidote to the tendency, precisely, in many religions, to become hide-bound in dogmas or fundamentalisms of various kinds (Chapple 1993:93).

What I want to show with these examples is that one can live the idea and the practice of non-violence or pluralism in the Jain way. What is more, all those who have familiarised themselves to some extent with Jainism have become Jains sui generis. Perhaps much of Jain teaching may sound strange, distant, exotic and even impracticable. It is not a question of conversation to any religion, or dressing up as saints. I am aware that is not always easy to incorporate an ascetic and soteriological path into our modern and secular contexts. This book is an invitation for each of us to interpret Jainism – or, while we are at it, any spiritual tradition – in a creative and fertile way. It is only by having other reference points that the possibility of revising one’s own convictions becomes available.

For me, the experience of Jainism has been supremely enriching. This is an only partially academic book. Above all it has been my own personal study, the fruit of my sympathy and attunement with many of the teachings of this tradition.

HERMENEUTICS

The learning of other wisdoms is no simple matter. It requires the audacity to surrender ourselves to be taught by others while yet not renouncing a critical spirit or convictions that we consider valid. I am conscious that reinterpreting the traditions, plucking a little from here and a little from there, could emerge the classic pot-pourri of beliefs à la carte without any kind of solid structure. It requires too a certain acuteness and intelligence, to know how to discriminate between what we can learn and what will be irreconcilable with our background; and a certain lucidity and imagination so as not to lapse into shallow superficialities or passing fads.

Freeing oneself of Eurocentric modes – whether one is Western or Indian – is a much more difficult task than it may at first seem. But we can open up an intercultural focus that will prove fruitful. And to open oneself up and to learn a new “language” we first have to listen to it. For that reason, I also present this work as a point of departure so that readers who are already familiar with Indian religions can move beyond the basic facts. This book is also an invitation to study the traditions of India: to study its philosophy, its art, its ways of life, its way of going into the world, its way of leaving the world…in short, its way of engaging with the spiritual dimension of life within Indic traditions and more particularly the Jain tradition. For that reason I have gone beyond merely providing information or historical facts to give deeper insights and considerations. I have sought to explain the meaning of some of these religious aspects and symbols:

10

What does this or that goal really mean, how does the tradition perceive its own history, how it can be that deity is lesser than an enlightened being, what is a sacred text, what feeding a monk means, etc.

Every anthropological, Indological, historical or sociological study of South Asia is a work of interpretation. There are points where readers may have the impression that I have forsaken my approach of writing for the intelligent lay reader and have ventured onto ground only suitable for experts. That is not my intention. My basic working assumption is that readers want something a little more stimulating than a mere compilation of facts. They will want to know about the deeper meaning of the spirituality and anthropology of a civilisation. To do so, they must (if they are not from an Indian or Indologist background) submerge themselves in an unfamiliar world and allow themselves to be impregnated by a mentality that understands things from what is at times a radically different perspective. And to be able to interpret the thinking and behaviour of India it will be necessary to empty the mind of certain constructs, categories, ways of understanding the world or religion, that are typical of the Western traditions.