Corporate Funding was developed on Jul.24, 2024.

CFO Handbook: Part 1, Chapter 2 - Funding

First revision: Jul.24, 2024

Last change: Oct.8, 2024

Searched, gathered, Rearranged, Translated, and Compiled by Apirak Kanchanakongkha.

.

page 1

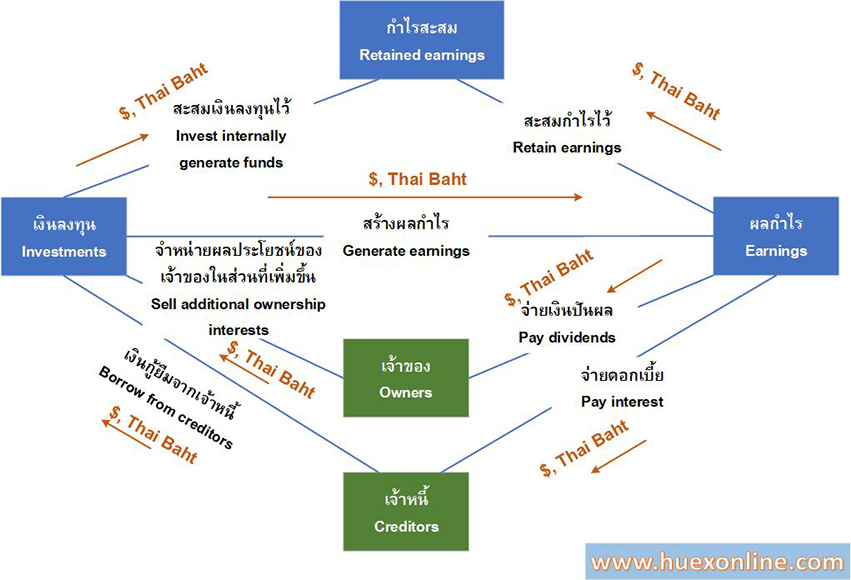

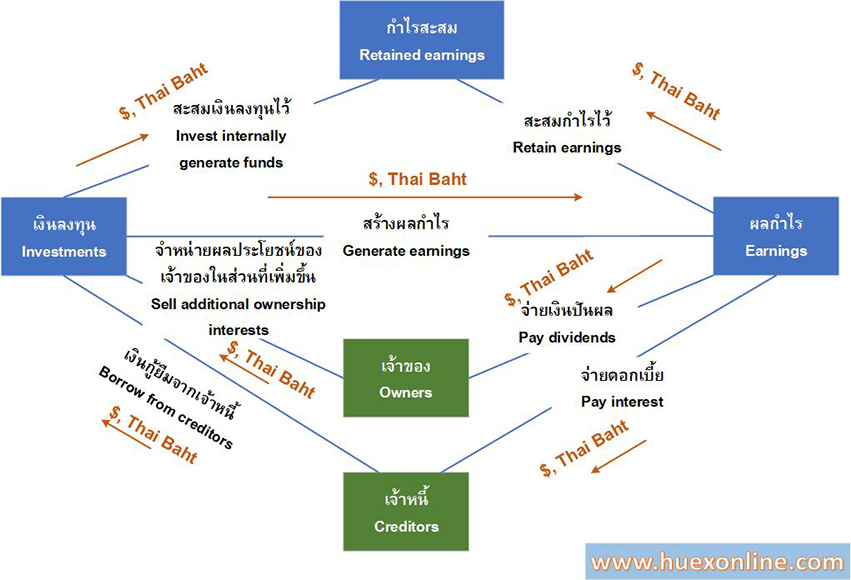

Figure 2.1 Financing a Company

Figure 2.1 Financing a Company

.

.

page 19

If the company has abundant earnings, the owners reap all that remains of the earnings after the creditors have been paid. If earnings are low, the creditors still must be paid what they are due, leaving the owners nothing out of the earnings. Failure to pay interest or principal as promised may result in financial distress. Financial distress is when a company makes decisions under pressure to satisfy its legal obligations to its creditors. These decisions may not be in the best interests of the company's owners.

With equity financing, there is no obligation. Though the company may choose to distribute funds to the owners in the form of cash dividends, there is no legal requirement to do so. Furthermore, interest paid on debt is deductible for tax purposes, whereas dividend payments are not.

One measure of the extent to which debt is used to finance a company is the debt ratio, the ratio of debt to equity:

Debt

Debt ratio = -----------

Equity

This is a relative measure of debt to equity. The greater the debt ratio, the greater the use of debt for financing operations relative to equity financing. Another measure is the debt-to-asset ratio, which is the extent to which the assets of the company are financed with debt:

Debt

Debt-to-assets ratio = -----------

Total Assets

This is the proportion of debt in a company's capital structure, measured using the book or carrying value of the debt and assets.

It is often helpful to focus on the long-term capital of a company when evaluating the capital structure of a company, looking at the interest-bearing debt of the company in comparison with the company's equity or with its capital. A company's capital is the sum of its interest-bearing debt and equity. The debt ratio can be restated as the ratio of the interest-bearing debt of the company to the equity:

.

.

page 20

Interest-bearing debt

Debt-equity ratio = -------------------------

Equity

And the debt-to-assets can be restated as the proportion of interest-bearing debt of the company's capital:

Interest-bearing debt

Debt-to-capital ratio = -------------------------

Total capital

By focusing on long-term capital, a company's working capital decisions that affect current liabilities, such as accounts payable, are removed from this analysis.

The equity component of these ratios is often stated in book or carrying value terms. However, when examining a company's capital structure from a market perspective, debt capital is often compared with the market value of equity. In this latter formulation, for example, the company's total capital is the sum of the interest-bearing debt and the market value of equity.

If market values of debt and equity are the most useful for decision-making, should the CFO ignore book values? No, because book values are also relevant in decision-making. For example, bond covenants are often specified in terms of book values or ratios of book values. As another example, dividends are distinguished from the return of capital based on the availability of the book value of retained earnings. Therefore, though the focus is primarily on the market values of capital, the CFO must also keep an eye on the book value of debt and equity.

There is a tendency for companies in some sectors and industries to use more debt than others. We see this by looking at the capital structure for different sectors from a survey & study information, where the proportion of assets financed with debt and equity are shown graphically in terms of the book values of debt and equity. We can make some generalizations about differences in capital structures across sectors:

- Companies that rely more on research and development for new products and technology - for example, pharmaceutical companies - tend to have lower debt-to-asset ratios than companies without such research and development needs.

- Companies that require a relatively heavy investment in fixed assets tend to have lower debt-to-asset ratios.

It is also interesting to see how debt ratios compare within sectors and with industries within a sector. For example, within the utilities sector, the electric utility industry uses less debt than both the water and gas industries.

.

.

page 21

Yet, debt ratios vary within each industry. For example, in the beverage industry, Cott Corporation, a maker of retail-brand soft drinks, has a much higher portion of debt in its capital structure than, say, the Coca-Cola Company.

Why do some industries tend to have higher debt ratios than others? By examining the role of financial leveraging, financial distress, and taxes, we can explain some of the variations in debt ratios among industries. By analyzing these factors, we can explain how the company's value may be affected by its capital structure.

CONCEPT OF LEVERAGE

The capital structure decision involves managing the risks associated with the company's business and financing decisions. The concept of leverage - in its operations and financing - plays a role in the company's risk because leverage exaggerates outcomes, good or bad.

.

.

page 22

Consider the simple example of a company with fixed and variable expenses. Suppose it has one product with a sales price of Thai Baht (THB) 100 per unit and variable costs of Thai Baht 40 per unit. This means the company has a THB 60 profit per unit before considering any fixed expenses. This THB 60 is the product's contribution margin - the amount available to cover fixed expenses. Suppose the company's fixed expenses are THB 20 million. If the company produces and sells 250,000 units, it has a loss of THB 5 million; if it produces and sells 1 million units, it has a profit of THB 40 million. The company would have to produce and sell 1/3 million units before covering its fixed expenses; producing and selling more than 1/3 million produces a profit, and producing less than 1/3 million generates a loss. This 1/3 million is the break-even point: the number of units produced and sold such that the product of the units sold and unit price covers the variable and fixed expenses.

The relation between the fixed cost, F, and the contribution margin can be specified in terms of the break-even quantity, QBE, the price per unit, P, the variable cost per unit, V, and the fixed costs:

. F

QBE = ----------------

(P - V)

Looking at the point from a broader range of units produced and sold, as shown in Panel A of Figure 2.3, the profit is upward sloping, with a slope of THB 60: Producing one additional unit produces a change in profit of THB 60, which is the contribution margin.

1

1

1