1 Bṛhadāraṇyaka Up., III 8, 8. In the M.B. the Lord who is the teacher tells Nārada that His real form is “invisible, unsmellable, untouchable, quality-less, devoid or parts, unborn, eternal, permanent and actionless.” See Śāntiparva, 339, 21-38. It is the “cloud of unknowing” or what the Areopagite calls the “superluminous darkness,” “the silent desert of the divinity…who is properly no being” in the words of Eckhart. Cp. Angelus Silesius: “God is mere nothing… to Him belongs neither now nor here.” Cp. Also Plotinus: “Generative of all, the Unity is none of all, neither thing nor quality, nor intellect nor soul, not in motion, not at rest, not in place, not in time; it is the self-defined, unique in form or, better, formless, existing before Form was or Movement or Rest, all of which are attachments of Being and make Being the manifold it is.” (Enneads, E.T., by Mackenna, VI, 9.)

2 II, 25.

3 XIII, 12; XIII, 15-17.

4 Īśa Up., 5: see also Muṇḍaka Up., II, I, 6-8; Kaṭha Up., II, 14; Bṛhadāraṇyaka Up., II, 37; Śvetāśvatara Up., III, 17.

5 Bahir antaś ca bhūtānām, XIII, 15.

23

…again and again.”1 “Who would have exerted, who would have lived, if this supreme bliss had not been in the heavens?”2 The theistic emphasis becomes prominent in the Śvetāśvatara Up. “He, who is one and without any colour (visible form), by the manifold wielding of His power, ordains many colours (forms) with a concealed purpose and into whom, in the beginning and the end, the universe dissolves, He is the God. May He endow us with an understanding which leads to good actions.”3 Again “Thou art the woman, thou art the man; thou art the youth and also the maiden; thou as an old man totterest with a sick, being born. Thou art facing all directions.”4 Again, “His form is not capable of being seen; with the eye no one sees Him. They who know Him thus with the heart, with the mind, as abiding in the heart, become immortal.”5 He is a universal God who Himself is the universe which He includes within His own being. He is the light within us, hṛdyantar jyotiḥ. He is the Supreme whose shadow is life and death.6

In the Upaniṣads, we have the account of the Supreme as the Immutable and the Unthinkable as also the view that He is the Lord of the universe. Though He is the source of all that is, He is Himself unmoved for ever.7 The Eternal Reality not only supports existence but is also the active power in the world. God is both transcendent, dwelling in light inaccessible and yet in Augustine’s phrase “more intimate to the soul than the soul to itself.” The Upaniṣad speaks of two birds perched on one tree, one of whom eats the fruits and the other eats not but watches, the silent witness withdrawn from enjoyment.8 Impersonality and

---------------

1 yo devo’gnau yo’psu yo viśvam bhuvanam āviveśa

yo oṣadhiṣu yo vanaspatiṣu tasmai devāya namonamaḥ.

2 Ko hyevānyāt kaḥ prāṇyāt yad eṣa ākāśa ānando na syāt?

3 IV, 1.

4 IV, 3.

5 IV, 20.

6 Ṛg. Veda, X, 121, 2: see also Kaṭha Up., III, 1. Cp. Deuteronomy: “I kill and make alive,” xxxii. 39.

7 Cp. Rūmi: “Thy light is at once joined to all things and apart from all.” Shams-i-Tabriz (E.T. By Nicholson), Ode IX.

8 Muṇḍaka Up., III, 1, 1-3. Cp. Boehme: “And the deep of the darkness is as great as the habitation of the light; and they stand not one distant from the other but together in one another and neither of them hath beginning nor end.” Three Principles, XIV, 76.

24

Personality are not arbitrary constructions or fictions of the mind. They are two ways of looking at the Eternal. The Supreme in its absolute self-existence is Brahman, the Absolute and as the Lord and Creator containing and controlling all, is Īśvara, the God. “Whether the Supreme is regarded as undetermined or determined, this Śiva should be known as eternal; undetermined He is, when viewed as different from the creation and determined, when He is everything.”1 If the world is a cosmos and not an amorphous uncertainty, it is due to the oversight of God. The Bhāgavata makes out that the one Reality which is of the nature of undivided consciousness is called Brahman, the Supreme Self or God.2 He is the ultimate principle, the real self in us as well as the God of worship. The Supreme is at once the transcendental aspect, it is the pure self unaffected by any action or experience, detached, unconcerned. In its dynamic cosmic aspect, It not only supports but governs the whole cosmic action and this very Self which is one in all and above all is present in the individual.3

Īśvara is not responsible for evil except in an indirect way. If the universe consists of active choosing individuals who can be influenced but not controlled, for God is not a dictator, conflict is inevitable. To hold that the world consists of free spirits means that evil is possible and probable. The alternative to a mechanical world is a world of risk and adventure. If all tendencies to error, ugliness and evil are to be excluded, there can be no seeking of the true, the beautiful and the good. If there is to be an active willing of these ideals of truth, beauty and goodness, then their opposites of error, ugliness and evil are not merely abstract possibilities but

---------------

1 nirguṇas saguṇas’ ceti śiva jñeyaḥ sanātanaḥ

nirguṇaḥ prakṛter anyaḥ, saguṇas sakala smṛtaḥ.

2 vadanti tat tattvavidḥ tattvaṁ yaj jñānam advayam

brahmeti paramātmeti bhagavān iti śabdyate.

Cp. Also:

utpattiṁ ca vināśaṁ ca bhūtānām āgatiṁ gatim

vetti vidyām avidyāṁ ca sa vācyo bhagavān iti.

3 Cp. Ś. On Bṛhadāraṇyaka Up., III, 8, 12. Roughly we may say that the Self in its transcendental, cosmic and individual aspects answers to the Christian Trinity of Father, Son and Holy Ghost.

25

Positive tendencies which we have to resist. For the Gītā, the world is the scene of an active struggle between good and evil in which God is deeply interested. He pours out His wealth of love in helping man to resist all that makes for error, ugliness and evil. As God is completely good and His love is boundless, He is concerned about the suffering of the world. God is omnipotent because there are no external limits to His power. The social nature of the world is not imposed on God, but is willed by Him. To the question, whether God’s omniscience includes a foreknowledge of the way in which men will behave and use or abuse their freedom of choice, we can only say that what God does not know is not a fact. He knows that the tendencies are indeterminate and when they become actualized, He is aware of them. The law of karma does not limit God’s omnipotence. The Hindu thinkers even during the period of the composition of the Ṛg. Veda, knew about the reasonableness and lawabidingness of nature. Ṛta or order embraces all things. The reign of law is the mind and will of God and cannot therefore be regarded as a limitation of His power. The personal Lord of the universe has a side in time, which is subject to change.

The emphasis of the Gītā is on the Supreme as the personal God who creates the perceptible world by His nature (prakṛti). He resides in the heart of every being;1 He is the enjoyer and lord of all sacrifices.2 He stirs our hearts to devotion and grants our prayers. He is the source and sustainer of values. He enters into personal relations with us in worship and prayer.3 He is the source and sustainer of values. He enters into personal relations with us in worship and prayer.

The personal Īśvara is responsible for the creation, preservation and dissolution of the universe.4 The Supreme has two natures, the higher (parā) and the lower (aparā).5 The living souls represent the higher and the material medium the lower. God is responsible for both the ideal plan and the concrete medium through which the ideal becomes the

---------------

1 XVIII, 61.

2 IX, 24.

3 VII, 22.

4 Cp. Jacob Boehme: “Creation was the act of the Father; the incarnation that of the Son; while the end of the world will be brought about through the operation of the Holy Ghost.”

5 VII, 4-5.

26

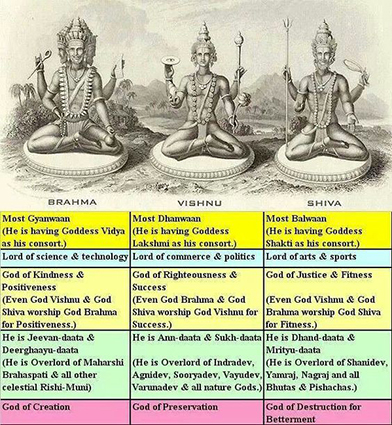

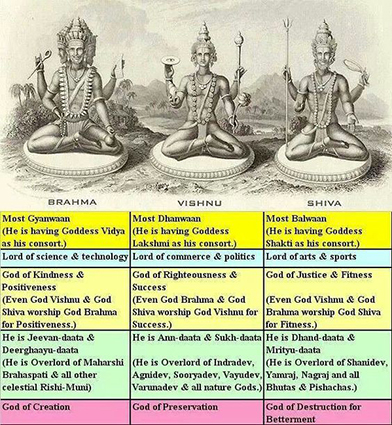

Actual, the conceptual becomes the cosmic. The concretization of the conceptual plan requires a fullness of existence, an objectification in the medium of potential matter. While God’s ideas are seeking for existence, the world of existence is striving for perfection. The Divine pattern and the potential matter, both these are derived from God, who is the beginning, the middle and the end, Brahmā, Viṣṇu and Śiva. God with His creative ideas is Brahmā. God who pours out His love and works with a patience which is matched only by His love is Viṣṇu, who is perpetually at work saving the world. When the conceptual becomes the cosmic, when heaven is established on earth, we have the fulfilment represented by Śiva. God is at the same time wisdom, love and perfection. The three functions cannot be torn apart. Brahmā, Viṣṇu and Śiva are fundamentally one though conceived in a threefold manner. The Gītā is interested in the process of redeeming the world. So the aspect of Viṣṇu is emphasized. Kṛṣṇa represents the Viṣṇu aspect of the Supreme.

Lord Brahmā, Lord Viṣṇu, and Lord Śiva, Source: www.printerest.com, Access date: Jan.26, 2024.

Viṣṇu is a familiar deity in the Ṛg. Veda. He is the great pervade, from viṣ to pervade.1 He is the internal controller who pervades the whole universe. He gathers to Himself in an ever-increasing measure the position and dignity of the Eternal Supreme. Taittirīya Araṇyaka says: “To Nārāyaṇa we bring worship; to Vāsudeva our meditations and in this may Viṣṇu assist us.”2

Kṛṣṇa,3 the teacher of the Gītā, becomes identified with Viṣṇu, the ancient Lord of the Sun, and Nārāyaṇa, an …

---------------

1 Amara states, vyāpake parameśvare. It is traced also from viṣ to enter. Taittirīya Up. Says: “Having created that world, he afterwards entered into it.” See also Padma Purāṇa. Viṣṇu as the Lord entered into prakṛti. sa eva bhagavān viṣṇuḥ prakṛtyām āviveśaḥ.

2 X, 1, 6. nārāyaṇāya vidmahe vāsudevāya dhīmahi tan no viṣṇuḥ pracodayāt. Nārāyaṇa says: “Being like the Sun, I cover the whole world with rays, and I am also the sustainer of all beings and am hence called Vāsudeva.” M.B., XII, 341, 41.

3 karṣati sarvaṁ kṛṣṇaḥ. He who attracts all or arouse devotion in all is kṛṣṇa. Vedāntaratnamañjūṣā (p. 52) says that Kṛṣṇa is so called because he removes the sins of his devotees, pāpaṁ karṣayati, nirmūlayati. Kṛṣṇa is derived from Kṛṣ, to scrape, because he scrapes or draws away all sins and other sources of evil from his devotees. kṛṣater vilekhanārthasya rūpaṁ bhaktajanapāpādidoṣakarṣaṇāt kṛṣṇaḥ. S.B.G., VI, 34.

27

…ancient God of cosmic character and the goal or resting place of gods and men.

The Real is the supracosmic, eternal, spaceless, timeless Brahman who supports this cosmic manifestation in space and time. He is the Universal Spirit, Paramātman, who enrolls the cosmic forms and movements. He is the Parameśvara who presides over the individual souls and movements of nature and controls the cosmic becoming. He is also the Puruṣottama, the Supreme Person, whose dual nature is manifested in the evolution of the cosmos. He fills our being. Illumines our understanding and sets in motion its hidden spring.1

All things partake of the duality of being and non-being from Puruṣottama downwards. Even God has the element of negativity or māyā though He controls it. He puts forth His active nature (svāṁ prakṛtīm) and controls the souls who work out their destinies along lines determined by their own natures. While all this is done by the Supreme through His native power exercised in this changing world, He has another aspect untouched by it all. He is the impersonal Absolute as well as the immanent will; He is the uncaused cause, the unmoved mover. While dwelling in man and…

---------------

1 He brings to the ignorant the light of knowledge, to the feeble the power of strength, to the sinner the liberation of forgiveness, to suffering the peace of mercy, to the comfortless comfort… jñānam ajñānām, śaktir aśaktānām, kṣamā sāparādhānām, kṛpā duḥkhinām, vātsālyaṁ sadoṣānām, śīlaṁ mandānām, ārjavaṁ kuṭilānām, sauhārdyaṁ duṣtahṛdayānām, mārdavaṁ viśleṣabhīrūṇām.

Cp. Also “Thou art joy and bliss, Thou the abode of peace: Thou dost destroy the sorrow of creatures and give them happiness.”

“ānandāmṛtarūpas tvaṁ ca śāntiniketanam

harasi prāṇināṁ duhkhaṁ vidadhāsi sadā sukham.”

“Thou art the refugee of the weak, the savior of the sinful.”

“dīnānāṁ śaraṇaṁ tvaṁ hi, pāpināṁ muktisādhanam.”

See also: “Thou who art radiance, fill me with radiance, Thou who art valour, fill me with valour: Thou who art strength, give me strength: Thou who art vitality, endow me with vitality: Thou who art wrath (against wrong), instill that wrath into me: Thou who art fortitude, fill me with fortitude.” tejo’si tejo mayi dehi, vīryam asi vīryaṁ mayi dehi, balam asi balaṁ mayi dehi, ojo’si ojo mayi dehi, manyur asi manyuṁ mayi dehi, saho’si sahomayi dehi. Śukla Yajur Veda, XIX, 9.

28

…nature. The Supreme is greater than both. The boundless universe in an endless space and time rests in Him and not He in it.1 The God of the Gītā cannot be identified with the cosmic process for He extends beyond it.2 Even in it He is manifest more in some aspects than in others. The charge of pantheism in the lower sense of the term cannot be urged against the Gītā view.3 While there is one reality that is ultimately perfect, everything that is concrete and actual is not equally perfect.

---------------

1 IX, 6, 10.

2 X, 41-2.

3 X, 21-37.