PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION

It is a pleasure to know that a new edition of this book is called for. It shows that, with all its defects, it has helped to rouse interest in Indian philosophy. I have not made many alternations in the text, but have added explanatory notes intended to clear difficulties, and an Appendix which deals with some of the controversial issues in the field of Indian thought raised by the first volume. My thanks are due to the Editor of Mind for his courtesy in permitting me to use in the Appendix the substance of an article which originally appeared in his pages (April 1926).

In preparing this edition, I have been considerably assisted by the suggestions of my friend Professor M. Hiriyanna of Mysore.

May 1929.

7

PREFACE

THOUGH the world has changed considerably in its outward material aspect, means of communication, scientific inventions, etc., there has not been any great change in its inner spiritual side. The old forces of hunger and love, and the simple joys and fears of the heart, belong to the permanent stuff of human nature. The true interests of humanity, the deep passions of religion, and the great problems of philosophy, have not been superseded as material things have been. Indian thought is a chapter of the history of the human mind, full of vital meaning for us. The ideas of great thinkers are never obsolete. They animate the progress that seems to kill them. The most ancient fancies sometimes startle us by their strikingly modern character, for insight does not depend on modernity.

Ignorance of the subject of Indian thought is profound. To the modern mind Indian philosophy means two or three “silly” notions about māyā, or the delusiveness of the world, karma, or belief in fate, and tyāga, or the ascetic desire to be rid of the flesh. Even these simple notions, it is said, are wrapped up in barbarous nomenclature and chaotic clouds of vapour and verbiage, looked upon by the “natives” as wonders of intellect. After a six-months’ tour from Calcutta to Cape Comorin, our modern æsthete dismisses the whole of Indian culture and philosophy as “pantheism,” “worthless scholasticism,” a mere play upon words,” “at all events nothing similar to Plato or Aristotle, or even Plotinus or Bacon.”

8

The intelligent student interested in philosophy will, however, find in Indian thought an extraordinary mass of material which for detail and variety has hardly any equal in any other part of the world. There is hardly any height of spiritual insight or rational philosophy attained in the world that has not its parallel in the vast stretch that lies between the early Vedic seers and the modern Naiyāyikas. Ancient India, to adapt Professor Gilbert Murray’s words in another context, “has the triumphant, if tragic, distinction of beginning at the very bottom and struggling, however precariously, to the very summits.”1 The naive utterances of the Vedic poets, the wonderous suggestiveness of the Upaniṣads, the marvellous psychological analyses of the Buddhists, and the stupendous system of Śaṁkara, are quite as interesting and instructive from the cultural point of view as the systems of Plato and Aristotle, Kant and Hegel, if only we study them in a true scientific frame of mind, without disrespect for the past or contempt for the alien. The special nomenclature of Indian philosophy which cannot be easily rendered into English accounts for the apparent strangeness of the intellectual landscape. If the outer difficulties are overcome, we feel the kindred throb of the human heart, which because human is neither Indian nor European. Even if Indian thought be not valuable from the culture point of view, it is yet entitled to consideration, if on no other ground, at least by reason of its contrast to other thought systems and its great influence over the mental life of Asia.

In the absence of accurate chronology, it is a misnomer to call anything a history. Nowhere is the difficulty of getting reliable historical evidence so extreme as in the case of Indian thought. The problem of determining the exact dates of early Indian systems is as fascinating as it –

-------------------------------------------------

1 Four Stages of Greek Religion, p. 15.

9

-is insoluble, and it has furnished a field for the wildest hypotheses, wonderful reconstruction and bold romance. The fragmentary condition of the material from out of which history has to be reconstructed is another obstacle. In these circumstances I must hesitate to call this work a History of Indian Philosophy.

In interpreting the doctrines of particular systems, I have tried to keep in close touch with the documents, give wherever possible a preliminary survey of the conditions that brought them into being, and estimate their indebtedness to the past as well as their contribution to the progress of thought. I have emphasised the essentials so as to prevent the meaning of the whole from being obscured by details, and attempted to avoid starting from any theory. Yet I fear I shall be misunderstood. The task of the historian is hard, especially in philosophy. However much he may try to assume the attitude of a mere chronicler and let the history in some fashion unfold its own inner meaning and continuity, furnish its own criticism of errors and partial insights, still the judgments and sympathies of the writer cannot long be hidden. Besides, Indian philosophy offers another difficulty. We have the commentaries which, being older, come nearer in time to the work commentaries which, being older, come nearer in time to the work commented upon. The presumption is that they will be more enlightening about the meaning of the texts. But when the commentators differ about their interpretations, one cannot stand silently by without offering some judgment on the conflict of views. Such personal expressions of opinion, however dangerous, can hardly be avoided. Effective exposition means criticism and evaluation, and I do not think it is necessary to abstain from criticism in order that I may give a fair and impartial statement. I can only hope that the subject is treated in a calm and dispassionate way, and that whatever the defects of the book, no

10

Attempt is made to wrest facts to suit a preconceived opinion. My aim has been not so much to narrate Indian views as to explain them, so as to bring them within the focus of Western traditions of thought. The analogies and parallels suggested between the two thought systems are not to be pressed too far, in view of the obvious fact that the philosophical speculations of India were formulated centuries ago, and had not behind them the brilliant achievements of modern science.

Particular parts of Indian philosophy have been studied with great care and thoroughness by many brilliant scholars in India, Europe and America. Some sections of philosophical literature have also been critically examined, but there has been no attempt to deal with the history of Indian thought as an undivided whole or a continuous development, in the light of which alone different thinkers and views can be fully understood. To set forth the growth of Indian philosophy from the dim dawn of history in its true perspective is an undertaking of the most formidable kind, and it certainly exceeds the single grasp of even the most industrious and learned scholar. Such a standard encyclopædia of Indian philosophy requires not only special aptitude and absolute devotion, but also wide culture and intelligent co-operation. This book professes to be no more than a general survey of Indian thought, a short outline of a vast subject. Even this is not quite easy. The necessary condensation imposes on the author a burden of responsibility, which is made more onerous by the fact that no one man can attempt to be an authority on all these varied fields of study, and that the writer is compelled to come to decisions on evidence which he himself cannot carefully weigh In matters of chronology, I have depended almost entirely on the results of research carried on by competent scholars. I am conscious that in surveying this wide field, much of –

11

interest is left untouched, and still more only very roughly sketched in. This work has no pretensions to completeness in any sense of the term. It attempts to give such a general statement of the main results as shall serve to introduce the subject to those whom it may not be known, and awaken if possible in some measure that interest for it to which it is so justly entitled. Even if it proves a failure, it may assist or at least encourage other attempts.

My original plan was to publish the two volumes together. Kind friends like Professor J. S. Mackenzie suggested to me the desirability of bringing out the first volume immediately. Since the preparation of the second volume would take some time and the first is complete in itself, I venture to punish it independently. A characteristic feature of many of the views discussed in this volume is that they are motived, not so much by the logical impulse to account for the riddles of existence, as by the practical need for a support in life. It has been difficult to avoid discussions of, what may appear to the reader, religious rather than philosophical issues, on account of the very close connexion between religion and philosophy in early Indian speculation. The second volume, however, will be of a more purely philosophical character, since a predominantly theoretical interest gets the upper hand in the darśanas or systems of philosophy, though the intimate connexion between knowledge and life is not lost sight of.

It is a pleasure to acknowledge my obligations to the many eminent orientalists whose works have been of great help to me in my studies. It is not possible to mention all their names, which will be found in the course of the book. Mention must, however, be made of Max Müller, Deussen, Keith, Jacobi, Garbe, Bhandarkar, Rhys Davids and Mrs. Rhys Davids, Oldenberg, Poussin, Suzuki and Sogen.

12

Several valuable works of recent publication, such as Professor Das Gupta’s History of Indian Philosophy and Sir Charles Eliot’s Hinduism and Buddhism, came to hand too late for use, after the MS. had been completed and sent to the publishers in December 1921. The bibliography given at the end of each chapter is by no means exhaustive. It is intended mainly for the guidance of the English reader.

My thanks are due to Professor J. S. Mackenzie and Mr. V. Subrahmanya Aiyar, who were good enough to read considerable parts of the MS. and the proofs. The book has profited much by their friendly and suggestive counsel. I am much indebted to Professor A. Berriedale Keith for reading the proofs and making many valuable comments. My greatest obligation, however, is to the Editor of the Library of Philosophy, Professor J. H. Muirhead, for his invaluable and most generous help in the preparation of the book for the press and previously. He undertook the laborious task of reading the book in the MS., and his suggestions and criticisms have been of the greatest assistance to me. I am also obliged to Sir Asutosh Mookerjee, Kt., C.S.I., for his constant encouragement and the facilities provided for higher work in the Post-Graduate Department of the Calcutta University.

November 1922

13

CONTENTS

| |

PAGE |

| PREFACE TO SECOND EDITION. . . . . |

5 |

| PREFACE |

. . . . . . . . |

7 |

|

CHAPTER I

|

| INTRODUCTION |

. . . . . . . |

21 |

| |

General characteristics of Indian philosophy – The natural situation of India – The dominance of the intellectual interest – The individuality of Indian philosophy – The influence of the West – The spiritual character of Indian thought – Its close relation to life and religion – The stress on the subjective – Psychological basis of metaphysics – Indian achievements in positive science – Speculative synthesis and scientific analysis – The brooding East – Monistic idealism – Its varieties, non-dualism, pure monism, modified monism and implicit monism – God is all-The intuitional nature of philosophy – Darśana - Śaṁkara’s qualifications of a candidate for the study of Philosophy – The constructive conservatism of Indian thought – The unity and continuity of Indian thought – Consideration of some charges levelled against Indian philosophy, such as pessimism, dogmatism, indifference to ethics and unprogressive character – The value of the study of Indian philosophy – The justification of the title “Indian Philosophy” – Historical method – The difficulty of a chronological treatment – The different periods of Indian thought – Vedic, epic, systematic and scholastic – “Indian” histories of Indian philosophy. |

|

| |

| PART 1 |

|

THE VEDIC PERIOD

|

|

CHAPTER II

|

| THE HYMNS OF THE ṚG-VEDA |

63 |

| |

The four Vedas – The parts of the Veda, the Mantras, the Brāhmaṇas, the Upaniṣads – The importance of the study of the hymns – Date and authorship – Different views of the teaching of the Hymns – Their philosophical tendencies – Religion – “Deva” – Naturalism and anthropomorphism – Heaven and Earth - Varuṇa - Ṛta – Sūrya – Uṣas – Soma – Yama – Indra - |

|

| |

14 |

| |

|

PAGE |

| |

Minor gods and goddesses – Classification of the Vedic deities – Monotheistic tendencies – The unity of nature – The unifying impulse of the logical mind – The implications of the religious consciousness – Henotheism – Viśvakarman, Bṛhaspati, Prajāpati and Hiraṇyagarbha – The rise of reflection and criticism – The philosophical inadequacy of monotheism – Monism – Philosophy and religion – The cosmological speculations of the Vedic hymns – The Nāsadīya Sūkta – The relation of the world to the Absolute – The Puruṣa Sūkta – Practical religion – Prayer – Sacrifice – The ethical rules – Karma – Asceticism – Caste – Future life – The two paths of the gods and the fathers – hell – rebirth – Conclusion. |

|

|

CHAPTER III

|

| TRANSITION TO THE UPANIṢADS |

117 |

| |

The general character of the Atharva-Veda – Conflict of cultures – The primitive religion of the Atharva-Veda – Magic and mysticism – The Yajur- Veda – The Brāhmaṇas – Their religion of sacrifice and prayer – The dominance of the priest – The authoritativeness of the Veda – Cosmology – Ethics – Caste – Future life. |

|

|

CHAPTER IV

|

| THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE UPANIṢADS |

137 |

| |

Introduction – The fluid and indefinite character of the teaching of the Upaniṣads – Western students of the Upaniṣads – Date – Early Upaniṣads – The great thinkers of the age – The Hymns the Ṛg-Veda and the doctrine of the Upaniṣads compared – Emphasis on the monistic side of the hymns – The shifting of the centre from the object to the subject – The pessimism of the Upaniṣads – The pessimistic implications of the conception of saṁsāra – Protest against the externalism of the Vedic religion – Subordination of the Vedic knowledge – The central problems of the Upaniṣads – Ultimate reality – The nature of Ātman distinguished from body, dream consciousness and empirical self – The different modes of consciousness, waking, dreaming, dreamless sleep and ecstasy – The influence of the Upaniṣads analysis of self on subsequent thought – The approach to reality from the object side – Matter, life, consciousness, intelligence and ānanda – Śaṁkara and Rāmānuja on the status of ānanda – Brahman and Ātman – Tat tvam asi – The positive character of Brahman – Intellect and intuition – Brahman and the world – Creation – The doctrine of māyā – Deussen’s view examined – Degree of reality – Are the Upaniṣads pantheistic ? – The finite self – The ethics of the Upaniṣads – The nature of the ideal – The metaphysical warrant for an ethical theory – Moral life - Its general features – Asceticism – Intellectualism – Jñāna, Karma and Upāsana – Morality and religion – Beyond good and evil – The religion of the Upaniṣads – Different forms – The highest state of freedom – The ambiguous accounts of it in the Upaniṣads – Evil – Suffering – Karma – Its value – The problem of freedom |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

15 |

| |

|

PAGE |

| |

‘- Future life and immortality – Psychology of the Upaniṣads – Non-Vedāntic tendencies in the Upaniṣads – Sāṁkhya – Yoga – Nyāya – General estimate of the thought of the Upaniṣads – Transition to the epic period. |

|

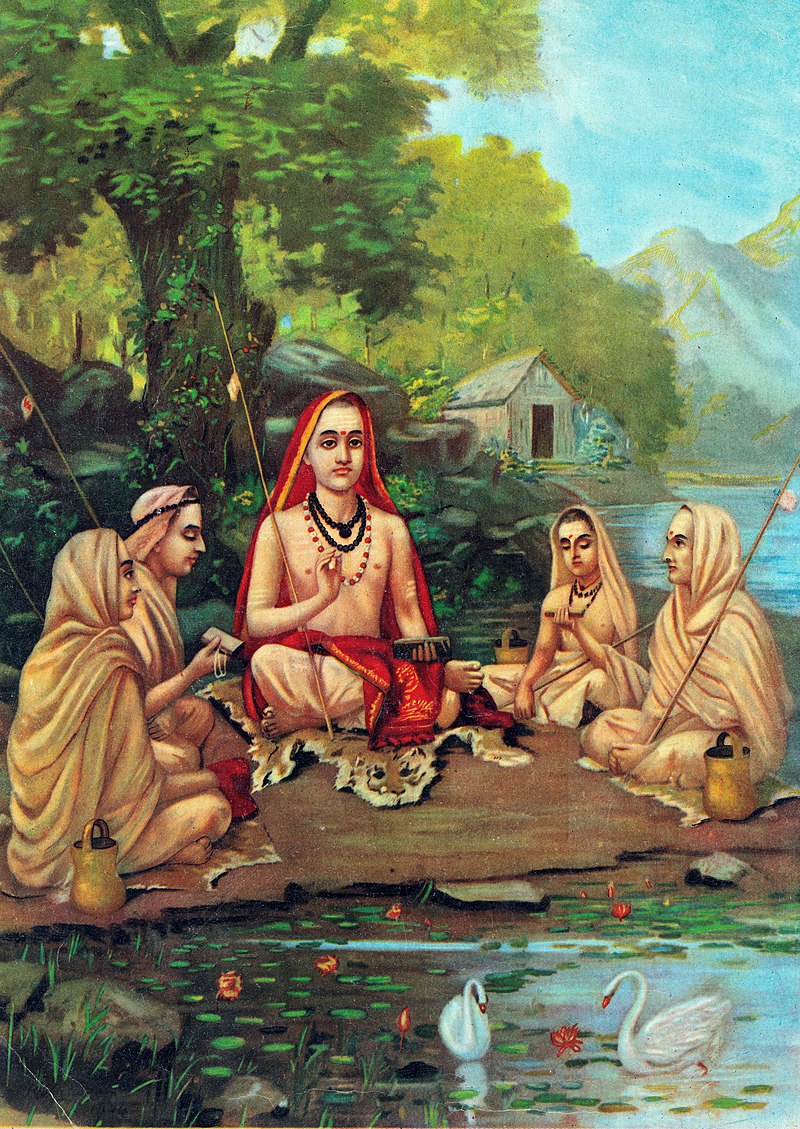

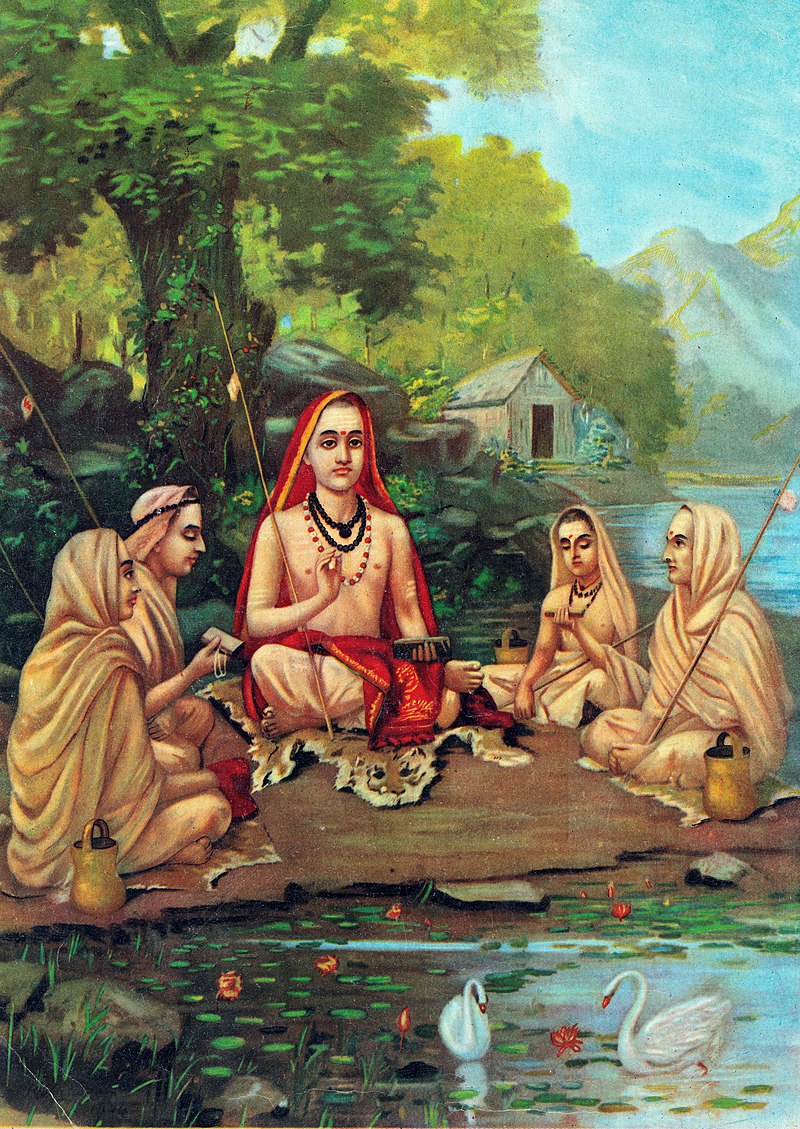

Adi Shankara with disciples, painted by Raja Ravi Varma, Create Circa 1904 date.,

source: en.wikipedia.org, accessed date: Jan.09, 2021.

| PART II |

|

THE EPIC PERIOD

|

|

CHAPTER V

|

| MATERIALISM . . . . . . . |

271 |

| |

The epic period 600 B.C. to A.D. 200 – Intellectual stir – Freedom of the thought- The Influence of the Upaniṣads – The political conditions of the time – The many-sided philosophic activity of the epic period – The three chief tendencies of ethical revolt, religious reconstruction and systematic philosophy – Common ideas of the age – Materialism – Its antecedents – Lokāyata – Theory of knowledge – Matter the only reality – Body and Mind – No future life – No God – Hedonistic ethics – The repudiation of the authority of the Vedas – The effects of the theory – Later criticism of materialism. |

|

The āsana in which Mahavira attained omniscience, File: Kevalajnana.jpg, created: 2 August 2008,

The āsana in which Mahavira attained omniscience, File: Kevalajnana.jpg, created: 2 August 2008,

sources: en.wikipedia.org, access date: May 12, 2020.

CHAPTER VI

|

| THE PLURALISTIC REALISM OF THE JAINAS |

286 |

| |

Jainism – Life of Vardhamāna – Division into Śvetāmbaras and Digambaras – Literature – Relation to Buddhism – The Sāṁkhya philosophy and the Upaniṣads – Jaina logic – Five kinds of knowledge – The Nayas and their divisions – Saptabhaṅgī – Criticism of the Jaina theory of knowledge – Its monistic implications – the psychological views of the Jainas – Soul – Body and mind – Jaina metaphysics – Substance and quality – Jīva and ajīva – Ākāśa, Dharma and Adharma – Time – Matter – The atomic theory – Karma – Leśyās – Jīva and their kinds – Jaina ethics – Human freedom – Ethics of Jainism and of Buddhism compared – Caste - Saṅgha – Attitude to God – Religion – Nirvāṇa – A critical estimate of the Jaina philosophy. |

|

CHAPTER VII

|

| THE ETHICAL IDEALISM OF EARLY BUDDHISM |

341 |

| |

Introduction – The evolution of Buddhist thought – Literature of early Buddhism – The three Piṭakas – Questions of King Milinda – Visuddhimagga - Life and personality of Buddha – Conditions of the time – The world of thought – The futility of |

|

16

| |

|

PAGE |

| |

Metaphysics – The state of religion – Moral life – Ethics independent of metaphysics and theology – The positive method of Buddha – His rationalism – Religion within the bounds of reason – Buddhism and the Upaniṣads – The four truths – The first truth of suffering – Is Buddhism pessimistic ? – The second truth of the causes of suffering – Impermanence of things – Ignorance – The dynamic conception of reality – Bergson – Identity of objects and continuity of process – Causation – Impermanence and momentariness – The world order – Being and becoming in the Upaniṣads and early Buddhism – Aristotle, Kant and Bergson - Śaṁkara on the kṣaṇikavāda – The nature of becoming – is it objective or only subjective ? – External reality – Body and mind – the empirical individual – Nairātmyavāda – Nature of the Ātman – Nāgasena’s theory of the soul – Its resemblance to Hume’s – The nature of the subject - Śaṁkara and Kant – Buddhist psychology – Its relation to modern psychology – Sense perception – Affection, will and knowledge – Association – Duration of mental states – Subconsciousness – Rebirth – Pratītyasamutpāda – Nidānas – Avidyā and the other links in the chain – The place of avidyā in Buddha’s metaphysics – the ethics of Buddhism – Its psychological basis – Analysis of the act – Good and evil – The middle path – the eightfold way – Buddhist Dhyāna and the Yoga philosophy – The ten fetters – The Arhat – Virtues and vices – The motive moral life – The inwardness of Buddhist morality – The charge of intellectualism – The complaint of asceticism – The order of mendicants - Saṅgha – Buddha’s attitude to caste and social reform – The authority of the Vedas – The ethical significance of Karma – Karma and freedom – Rebirth – Its mechanism - Nirvāṇa – Its nature and varieties – The Nirvāṇa of Buddhism and the Mokṣa of the Upaniṣads – God in early Buddhism – The criticism of the traditional proofs for the existence of God – The absolutist implications of Buddhist metaphysics – The deification of Buddha – Compromises with popular religion – Buddhist theory of knowledge – Buddha’s pragmatic agnosticism – Buddha’s silence on metaphysical problems – Kant and Buddha – The Inevitability of metaphysics - The unity of thought between Buddhism and the Upaniṣads – Buddhism and the Sāṁkhya theory – Success of Buddhism. |

|

|

CHAPTER VIII

|

| EPIC PHILOSOPHY . . . . . . |

477 |

| |

The readjustment of Brāhmanism – The epics – The Mahābhärata – Date – Its importance – The Rāmāyaṇa – The religious ferment – The common philosophical ideas – Durgā worship – Pāśupata system – Vāsudeva-Kṛṣṇa cult – Vaiṣṇavism – Pāñcarātra religion – The suspected influence of Christianity – The Cosmology of the Mahābhārata – The Sāṁkhya ideas in the Mahābhārata - Guṇas – Psychology – Ethics – Bhakti – Karma – Future life – Later Upaniṣads – The Śvetāśvatara Upaniṣad – The Code of Manu – Date – Cosmology and Ethics. |

|

17

|

CHAPTER IX

|

| |

PAGE |

| THE THEISM OF THE BHAGAVADGĪTĀ . . . . |

519 |

| |

The importance of the Gītā in Indian thought – Its universal significance – Date – Relation to the Mahābhārata – The Vedas – The Upaniṣads – Buddhism – The Bhāgavata religion – The Sāṁkhya and the Yoga – Indian commentaries on the Gītā – The Gītā ethics in based on metaphysics – The problem of reality – The real in the objective and the subjective worlds – Brahman and the world - Puruṣottama – Intuition and thought – Higher and lower prakṛti. – The avātaras – The nature of the universe – Māyā – Creation – The individual soul – Plurality of souls – Rebirth – The ethics of the Gītā – Reason, will and emotion – Jñāna mārga – Science and philosophy – Patanjali’s Yoga – The Jñāni – Bhakti mārga – The personality of God – The religious consciousness – Karma mārga – The problem of morality – The moral standard – Disinterested action – Guṇas – The Vedic theory of sacrifices – Caste – Is work compatible with mokṣa ? – The problem of human freedom – The integral life of spirit – Ultimate freedom and its character. |

|

|

CHAPTER X

|

| BUDDHISM AS A RELIGION . . . . . |

581 |

| |

The history of Buddhism after the death of Buddha – Aśoka – The Mahāyāna and the Hīnayāna – Northern and southern Buddhism – Literature – Hīnayāna doctrines – Metaphysics, ethics and religion – The rise of the Mahāyāna – Its monistic metaphysics – The religion of the Mahāyāna – Its resemblance to the Bhagavadgītā – The ethics of the Mahāyāna – The ten stages – Hīnayāna and Mahāyāna ethics compared – Nirvāṇa – Decline of Buddhism – The effects of Buddhism on Indian thought. |

|

|

CHAPTER XI

|

| THE SCHOOLS OF BUDDHISM . . . . . |

581 |

| |

Introduction – The four schools of realism and idealism – The Vaibhāṣikas – Nature of reality – Knowledge – Psychology – The Sautrāntikas – Knowledge of the external world – God and Nirvana – The Yogācāras – Their theory of knowledge – Nature of Ālayavijñāna – Subjectivism – Criticism of it by Śaṁkara and Kumārila – Individual self – Forms of knowledge – The Yogācāra theory of the world – Avidyā and Ālaya – Nirvāṇa – Ambiguity of Ālayavijñāna – The Mādhyamikas – Literature – The Mādhyamika criticism of the Yogācāra – Phenomenalism – Theory of relations – Two kinds of knowledge – Absolutism – Śūnyavada - Nirvāṇa – Ethics – Conclusion. |

|

18

| |

PAGE |

| APPENDIX . . . . . . . |

671 |

| |

The Method of Approach – The Comparative Standpoint – The Upaniṣads – Early Buddhism – The Negative, The Agnostic and Positive Views – Early Buddhism and the Upaniṣads – The Schools of Buddhism – Nagarjuna’s Theory of Reality – Śūnyavada and Advaita Vedānta. |

|

| NOTES . . . . . . . . |

705 |

| INDEX . . . . . . . . |

725 |

19

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

|

| A.V. |

. . |

Atharva-Veda. |

| B.G. |

. . |

Bhagavadgītā. |

| E.R.E. |

. . |

Encyclopædia of Religion and Ethics. |

| I.A. |

. . |

Indian Antiquary. |

| J.A.O.S. |

. . |

Journal of the American Oriental Society. |

| J.R.A.S. |

. . |

Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. |

| Milinda |

. . |

Questions of King Milinda. |

| N.S. |

. . |

Nyāya Sūtras. |

| O.S.T. |

. . |

Original Sanskrit Texts. |

| P. |

. . |

Pañcāstikāyasamayasāra. |

| P.M. |

. . |

Pūrva-Mīmāṁsā Sūtras. |

| R.B. |

. . |

Rāmānuja’s Bhāṣya on the Vedānta Sūtras. |

| R.B.G. |

. . |

Rāmānuja’s Bhāṣya on the Bhagavadgītā. |

| S.B. |

. . |

Śaṁkara’s Bhāṣya on the Vedānta Sūtras. |

| S.B.G. |

. . |

Śaṁkara’s Bhāṣya on the Bhagavadgītā. |

| S.B.E. |

. . |

Sacred Books of the East. |

| S.B.H. |

. . |

Sacred Books of the Hindus. |

| S.D.S. |

. . |

Sarvadarśanasaṁgraha. |

| S.K. |

. . |

Śāṁkhya Kāriķā. |

| Skt. |

. . |

Sanskrit. |

| S.S. |

. . |

Six Systems of Indian Philosophy by Max Műller. |

| S. Sūtras |

. . |

Śāṁkhya Sūtras. |

| S.S.S.S. |

. . |

Sarvasiddhāntasārasaṁgraha. |

| Up. |

. . |

Upaniṣads. |

| U.T.S. |

. . |

Umāsvāti’s Tattvārtha Sūtras. |

| V.S. |

. . |

Vedānta Sūtras. |

| W.B.T. |

. . |

Warren : Buddhism in Translations. |

| Y.S. |

. . |

Yoga Sūtras. |